Underweight

| Underweight | |

|---|---|

| |

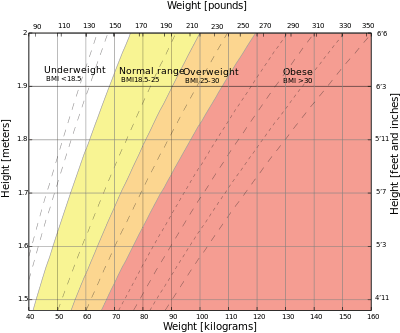

| The underweight range according to the Body Mass Index (BMI) is the white area on the chart. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | R62.8 |

| ICD-9-CM | 783.22 |

| MeSH | D013851 |

Underweight is a term describing a person whose body weight is considered too low to be healthy. The definition usually refers to people with a body mass index (BMI) of under 18.5[1] or a weight 15% to 20% below that normal for their age and height group.[2]

Causes

A person may be underweight due to genetics,[3][4] metabolism, drug use, lack of food (frequently due to poverty), or illness.

Being underweight is associated with certain medical conditions, including hyperthyroidism,[5] cancer,[6] or tuberculosis.[7] People with gastrointestinal or liver problems may be unable to absorb nutrients adequately. People with certain eating disorders can also be underweight due to lack of nutrients/over exercise.

Problems

Underweight might be secondary to or symptomatic of an underlying disease. Unexplained weight loss may require professional medical diagnosis.

Underweight can also be a primary causative condition. Severely underweight individuals may have poor physical stamina and a weak immune system, leaving them open to infection. According to Robert E. Black of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health (JHSPH), "Underweight status ... and micronutrient deficiencies also cause decreases in immune and non-immune host defenses, and should be classified as underlying causes of death if followed by infectious diseases that are the terminal associated causes."[8] People who are malnutrative underweight raise special concerns, as not only gross caloric intake may be inadequate, but also intake and absorption of other vital nutrients, especially essential amino acids and micro-nutrients such as vitamins and minerals.

In women, being severely underweight as a result of an eating disorder, or due to excessive strenuous exercise can result in amenorrhea (absence of menstruation),[9] infertility and, if gestational weight gain is too low, possible complications during pregnancy. Malnourishment can also cause anemia and hair loss.

Being underweight is an established[10] risk factor for osteoporosis, even for young people. This is seen in individuals suffering from the female athlete triad, when disordered eating or excessive exercise cause amenorrhea, hormone changes during anovulation leads to loss of bone mineral density.[11][12] After the occurrence of first spontaneous fractures the damage is often already irreversible.

Although being underweight has been reported to increase mortality at rates comparable to that seen in morbidly obese people,[13] the effect is much less drastic when restricted to non-smokers with no history of disease,[14] suggesting that smoking and disease-related weight loss are the leading causes of the observed effect.

Treatment

Diet

Underweight individuals may be advised to gain weight by increasing calorie intake. This can be done by eating a sufficient volume of sufficiently calorie-dense foods.[15] Body weight may also be increased through the consumption of liquid nutritional supplements.[16] Other nutritional supplements may be recommended for individuals with insufficient vitamin or mineral intake.[17][18]

Exercise

Another way for underweight people to gain weight is by exercising. Muscle hypertrophy increases body mass. Weight lifting exercises are effective in helping to improve muscle tone as well as helping with weight gain.[19] Weight lifting has also been shown to improve bone mineral density,[20] for which underweight people have an increased risk of deficiency.[21]

Exercise itself is catabolic, which results in a brief reduction in mass. The gain in weight that can result of it comes from the anabolic overcompensation when the body recovers and overcompensates via muscle hypertrophy. This can happen by an increase in the muscle proteins, or through enhanced storage of glycogen in muscles. Exercise can help stimulate a person's appetite if they are not inclined to eat.

Appetite stimulants

Certain drugs may increase appetite either as their primary effect or as a side effect. Antidepressants, such as mirtazapine or amitriptyline, and antipsychotics, particularly chlorpromazine and haloperidol as well as tetrahydrocannabinol (found in cannabis), all present an increase in appetite as a side effect. In states where it is approved, medicinal cannabis may be prescribed for severe appetite loss, such as that caused by cancer, AIDS, or severe levels of persistent anxiety. Other drugs which may increase appetite include certain benzodiazepines (such as diazepam), sedating antihistamines (such as diphenhydramine, promethazine or cyproheptadine[22]), or B vitamin supplements.

See also

References

- ↑ "Assessing Your Weight and Health Risk". National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ↑ Mahan, L. Kathleen (2000). Krause's Food, Nutrition & Diet Therapy, 10th Ed. Philadelphia: W,B. Saunders Co.

- ↑ "Body Shape 'Is Down to Genes'". Indian Express. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ↑ "'Skinny Gene' Exists". Science Daily. September 5, 2007. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ↑ Milas, Kresimira. "Hyperthyroidism Symptoms - Signs and symptoms caused by excessive amounts of thyroid hormones". Endocrine Web. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ↑ "Signs and Symptoms of Cancer". American Cancer Society. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ↑ Hira, S. K.; H. L. Dupont; D. N. Lanjewar; Y. N. Dholakia (1998). "Severe weight loss: the predominant clinical presentation of tuberculosis in patients with HIV infection in India.". National Medical Journal of India. 11 (6): 256–258. PMID 10083790.

- ↑ Black, Robert E.; Morris, Saul S.; Bryce, Jennifer (28 June 2003), "Where and Why are 10 Million Children Dying Every Year?", The Lancet, 361: 2226–34, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8, PMID 12842379

- ↑ http://contemporaryobgyn.modernmedicine.com/%5Bnode-source-domain-raw%5D/news/modernmedicine/modern-medicine-now/amenorrhea-caused-extremes-body-mas?page=full

- ↑ Gjesdal; Halse, JI; Eide, GE; Brun, JG; Tell, GS (2008). "Impact of lean mass and fat mass on bone mineral density: the Hordaland Health Study". Maturitas. 59 (2): 191–200. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.11.002. PMID 18221845.

- ↑ Nattiv; Agostini, R; Drinkwater, B; Yeager, KK (1994). "The female athlete triad. The inter-relatedness of disordered eating, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis". Clinics in sports medicine. 13 (2): 405–18. PMID 8013041.

- ↑ Wilson; Wolman, RL (1994). "Osteoporosis and fracture complications in an amenorrhoeic athlete". British journal of rheumatology. 33 (5): 480–1. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/33.5.480. PMID 8173855.

- ↑ Waaler HT. (1984). "Height, weight and mortality. The Norwegian experience". Acta Med Scand Suppl. 215 (679): 1–56. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1984.tb12901.x. PMID 6585126.

- ↑ Body Weight and Mortality:What is the optimum weight for a longer life?.

- ↑ Zeratsky, Katherine (23 August 2011). "Underweight? See how to add pounds healthfully". Nutrition and healthy eating. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ↑ "Healthy Weight Gain". Children's Hospital Boston, Center for Young Women's Health. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Gain Weight and Be Healthy". About.com. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Achieving Healthy Weight Gain". Health Central. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Men's Health". Men's Health. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ↑ Gleeson, Peggy; Elizabeth J. Protas; Adrian D. Leblanc; Victor S. Schneider; Harlan J. Evans (February 1990). "Effects of weight lifting on bone mineral density in premenopausal women". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 5 (2): 153–158. doi:10.1002/jbmr.5650050208. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ↑ Coin, A.; G. Sergi; P. Benincà; L. Lupoli; G. Cinti; L. Ferrara; G. Benedetti; G. Tomasi; C. Pisent; G. Enzi (2000). "Bone Mineral Density and Body Composition in Underweight and Normal Elderly Subjects". Osteoporosis International. 11 (12). doi:10.1007/s001980070026. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ↑ Long-term trial of cyproheptadine as an appetite stimulant in cystic fibrosis | Wiley Online Library