Welland Canal

| Welland Canal | |

|---|---|

|

A ship transits the Welland Canal in St. Catharines, with the Homer Lift Bridge and Garden City Skyway in background. | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 27 miles (43 km) |

| Maximum boat length | 740 ft 0 in (225.6 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 78 ft 0 in (23.8 m) |

| Locks | 8 |

| Status | Open |

| Navigation authority | Saint Lawrence Seaway Management Corporation |

| History | |

| Original owner | Welland Canal Company |

| Principal engineer | Hiram Tibbetts |

| Construction began | 1824 |

| Date completed | 1829 |

| Date extended | 1833 |

| Date restored | August 6, 1932 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Lake Ontario at Port Weller |

| End point | Lake Erie at Port Colborne |

Welland Canals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

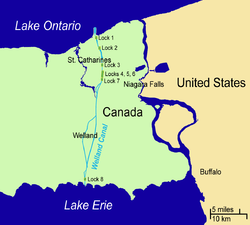

The Welland Canal is a ship canal in Ontario, Canada, connecting Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. Traversing the Niagara Peninsula from Port Weller to Port Colborne, the canal forms a key section of the St. Lawrence Seaway, enabling ships to ascend and descend the Niagara Escarpment and bypass Niagara Falls.

Approximately 40,000,000 tonnes of cargo are carried through the Welland Canal annually by a traffic of about 3,000 ocean and Great Lakes vessels. This canal was a major factor in the growth of the city of Toronto. The original canal and its successors allowed goods from Great Lakes ports such as Cleveland, Detroit, and Chicago, as well as heavily industrialized areas of the United States and Ontario, to be shipped to the port of Montreal or to Quebec City, where they were usually reloaded onto ocean-going vessels for international shipping.

By providing a relatively short and direct connection to Lake Erie, the Welland Canal eclipsed other, narrower canals in the region as a commercial traffic route for Great Lakes navigation, such as the Trent-Severn Waterway and, significantly, the Erie Canal, which linked the Atlantic and Lake Erie via New York City and Buffalo, New York.

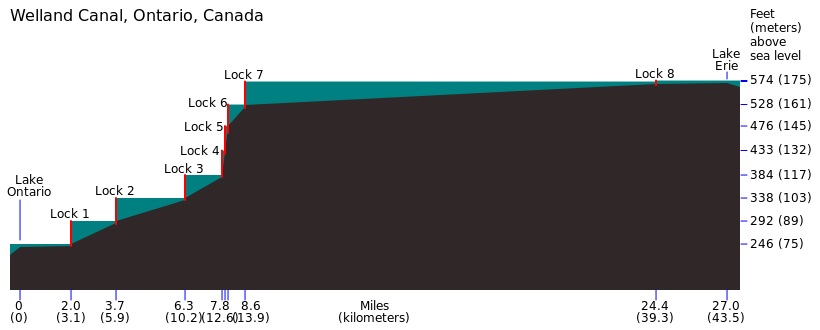

The southern, Lake Erie terminus of the canal is 99.5 metres (326 feet) higher than the northern terminus on Lake Ontario. The canal includes eight 24.4-metre-wide (80 ft) ship locks.[1] Seven of the locks (Locks 1–7, the 'Lift' locks) are 233.5 m (766 ft) long and raise (or lower) passing ships by between 13 and 15 m (43 and 49 ft) each. The southernmost lock, (Lock 8 – the 'Guard' or 'Control' lock) is 349.9 m (1,148 ft) in length.[2] The Garden City Skyway passes over the canal, restricting the maximum height of the masts of the ships allowed on this canal to 35.5 m (116 ft).

All other highway or railroad crossings of the Welland Canal are either movable bridges (of the vertical lift or bascule bridge types) or subterranean tunnels. The maximum permissible length of a ship in this canal is 225.5 metres (740 feet). It takes ships an average of about eleven hours to traverse the entire length of the Welland Canal.

History

Before the digging of the Welland Canal, shipping traffic between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie used a portage road between Chippawa, Ontario, and Queenston, Ontario, both of which are located on the Niagara River—above and below Niagara Falls, respectively.

First Welland Canal

The Welland Canal Company was incorporated by the Province of Upper Canada, in 1824, after a petition by nine "freeholders of the District of Niagara". One of the petitioners was William Hamilton Merritt, who was in part looking to provide a regular flow of water for his watermills. The construction began at Allanburg, Ontario, on November 30, at a point now marked as such on the west end of Bridge No. 11 (formerly Highway 20). This canal opened for a trial run on November 30, 1829 (exactly five years, to the day, after the ground-breaking in 1824). After a short ceremony at Lock One, in Port Dalhousie, the schooner Anne & Jane (also called "Annie & Jane" in some texts[3]) made the first transit, upbound to Buffalo, N.Y., with Merritt as a passenger on her deck.

The first canal ran from Port Dalhousie, Ontario on Lake Ontario south along Twelve Mile Creek to St. Catharines. From there it took a winding route up the Niagara Escarpment through Merritton, Ontario to Thorold, where it continued south via Allanburg to Port Robinson, Ontario on the Welland River. Ships went east (downstream) on the Welland River to Chippawa, at the south (upper) end of the old portage road, where they made a sharp right turn into the Niagara River, upstream towards Lake Erie. Originally, the section between Allanburg and Port Robinson was planned to be carried in a subterranean tunnel. However, the sandy soil in this part of Ontario made a tunnel infeasible, and a deep open-cut canal was dug instead.

A southern extension from Port Robinson opened in 1833, with the founding of Port Colborne. This extension followed the Welland River south to Welland (known then as the settlement of Aqueduct, for the wooden aqueduct that carried the canal over the Welland River at that point), and then split to run south to Port Colborne on Lake Erie. A feeder canal ran southwest from Welland to another point on Lake Erie, just west of Rock Point Provincial Park. With the opening of the extension, the canal stretched 44 km (27 mi) between the two lakes, with 40 wooden locks. The minimum lock size was 33.5 by 6.7 m (110 by 22 ft), with a minimum canal depth of 2.4 m (7.9 ft).

Deterioration of the wood used in the 40 locks and the increasing size of ships led to demand for the Second Welland Canal, which used cut stone locks, within just a few years.[4]

Second Welland Canal

In 1839 the government of Upper Canada approved the purchase of shares in the private canal company in response to the company's continuing financial problems in the face of the continental financial panic of 1837. The public buyout was completed in 1841, and work began to deepen the canal and to reduce the number of locks to 27, each 45.7 by 8.1 m (150 by 27 ft). By 1848, a 2.7 m (8.9 ft) deep path was completed, not only through the Welland Canal but also the rest of the way to the Atlantic Ocean via the St. Lawrence Seaway.

Competition came in 1854 with the opening of the Erie and Ontario Railway, running parallel to the original portage road. In 1859, the Welland Railway opened, parallel to the canal and with the same endpoints. But this railway was affiliated with the canal, and was actually used to help transfer cargoes from the lake ships, which were too large for the small canal locks, to the other end of the canal (The remnants of this railway are today owned by the Trillium RR). Smaller ships called "canallers" also took a part of these loads. Due to this problem, it was soon apparent that the canal would have to be enlarged again.

Third Welland Canal

In 1887, a new shorter alignment was completed between St. Catharines and Port Dalhousie. One of the most interesting features of this third Welland Canal was the Merritton Tunnel on the Grand Trunk Railway line that ran under the canal at Lock 18. Another tunnel, nearby, carried the canal over a sunken section of the St David's Road. The new route had a minimum depth of 4.3 m (14 ft) with 26 stone locks, each 82.3 m (270 ft) long by 13.7 m (45 ft) wide. Even so, the canal was still too small for many boats.

Fourth (current) Welland Canal

Construction on the current canal began in 1913 and was completed and officially opened on August 6, 1932. Dredging to the planned 25 foot depth was not completed until 1935. The route was again changed north of St. Catharines, now running directly north to Port Weller. In this configuration, there are eight locks, seven at the Niagara Escarpment and the eighth, a guard lock, at Port Colborne to adjust with the varying water depth in Lake Erie. The depth was now 7.6 m (25 ft), with locks 233.5 m (766 ft) long by 24.4 m (80 ft) wide. This canal is officially known now as the Welland Ship Canal.

Welland By-Pass

In the 1950s, with the building of the present St. Lawrence Seaway, a standard depth of 8.2 m (27 ft) was adopted. The 13.4-kilometre (8.3 mi) long Welland By-Pass, built between 1967 and 1972, opened for the 1973 shipping season, providing a new and shorter alignment between Port Robinson and Port Colborne and by-passing downtown Welland. All three crossings of the new alignment—one an aqueduct for the Welland River—were built as tunnels. Around the same time, the Thorold Tunnel was built at Thorold and several bridges were removed.

Fifth (proposed but uncompleted) Welland Canal

These projects were to be tied into a proposed new canal, titled the Fifth Welland Canal, which was planned to by-pass most of the existing canal to the east and to cross the Niagara Escarpment in one large 'superlock'. While land for the project was expropriated and the design finalized, the project never got past the initial construction stages and has since been shelved. The present (4th) canal is scheduled to be replaced by 2030, almost exactly 100 years after it first opened, and 200 years since the first full shipping season, in 1830, of the original canal.

Accidents

On June 20, 1912, the government survey steamer La Canadienne lost control due to mechanical problems in the engine room and smashed into the upstream gates of Lock No. 22 of the 3rd Welland Canal, forcing them open by six inches. The resulting surge of water flooded downstream, cresting the upstream gates of Lock No. 21 where five boys were fishing. One boy ran to safety and one of the boys, David Boucke, was saved by a government surveyor Hugh McGuire. But the remaining three, Willie Wallace Tifney (age 5), Willie Tacke (age 5) and Leonard Bretwick (age 4)[5] were knocked into the water, drowning in the surge.

On August 25, 1974, the northbound ore-carrier Steelton struck Bridge 12 in Port Robinson. The bridge was rising and the impact knocked the bridge over, destroying it. No one was killed. The bridge master, Albert Beaver, and a watchman on the ship suffered minor injuries. The bridge has not been replaced and the inhabitants of Port Robinson have been served by a ferry for many years. The Welland Public Library archive has images of the aftermath.

On August 11, 2001, the lake freighter Windoc collided with Bridge 11 in Allanburg, closing vessel traffic on the Welland Canal for two days. The accident destroyed the ship's wheelhouse and funnel (chimney), ignited a large fire on board, and caused minor damage to the vertical lift bridge. The accident and portions of its aftermath were captured on amateur video.[6] The vessel was a total loss, but there were no reported injuries, and no pollution to the waterway. The damage to the bridge was focused on the centre of the vertical-lift span. It was repaired over a number of weeks and reopened to vehicular traffic on November 16, 2001. The Marine Investigation Report concluded, "it is likely that the [vertical lift bridge] operator's performance was impaired while the bridge span was lowered onto the Windoc."[7][8]

At around noon on Wednesday September 30, 2015, the Lena J cargo ship collided with Bridge 19 in Port Colborne, closing the bridge to all vehicle and pedestrian traffic until an assessment could be made on the condition of the bridge.[9][10] The vessel had sustained damage to its bridge, but was still able to continue on its voyage to Burns Harbour, Indiana. Pictures of the damage sustained to the vessel and Bridge 19 were captured.[11] On Friday October 1, 2015, Chris Lee, an acting direct engineer for the City of Port Colborne, said that the St. Lawrence Seaway Management Corporation (SLSMC) will likely close the bridge to all vehicle traffic until the end of the year. However, pedestrians will be able to cross the bridge, and emergency services will be able to cross the bridge on a limited basis.[12][13][14][15] On Tuesday October 6, 2015, the City of Port Colborne released a media statement, which stated that Bridge 19, "will remain closed to vehicular traffic until after the close of the shipping season in December. Repairs will begin in early January." Detour routes have been planned and mapped by the City of Port Colborne and the City of Welland in order to ease the flow of traffic over Bridge 19A.[16]

Sabotage

The Welland Canal has been the focus of plots on a number of occasions throughout its existence. However, only two have ever been carried out. The earliest and potentially most devastating attack occurred on September 9, 1841[17] at Lock No. 37 (Allanburg) of the First Welland Canal (43°04′41″N 79°12′36″W / 43.07796°N 79.20991°W), [approximately 180 m north of today's Allanburg bridge][18] when an explosive charge destroyed one of the lock gates. However, a catastrophic flood was prevented when a guard gate located upstream of the lock closed into place preventing the upstream waters from careening down the route of the Canal and causing further damage and possible injury or loss of life. It was suspected that Benjamin Lett was responsible for the explosion.

On April 21, 1900 about 6:30 in the evening,[19] a dynamite charge was set off against the hinges of Lock No. 24 of the Third Welland Canal (just to the east of Lock No. 7 of today's canal (43°07′23″N 79°11′33″W / 43.122976°N 79.192372°W)), doing minor damage. This time, the saboteurs were caught in nearby Thorold. John Walsh, John Nolan and the ringleader "Dynamite" Luke Dillon (a member of Clan-na-Gael)[20] were tried at the Welland Courthouse and found guilty, receiving life sentences at Kingston Penitentiary. The "star witness" at the trial was a 16-year-old Thorold girl named Euphemia Constable, who caught a good look at the bombers before being knocked unconscious by the blast. While waiting to testify, the girl received death threats, but, they turned out to be a hoax. As for the prisoners, Nolan lost his sanity while incarcerated, John Walsh was eventually released while Luke Dillon remained in custody until July 12, 1914[21]

The First World War brought with it plots against the canal and the most notable of them came to be known as "The Von Papen Plot". In April 1916, a United States federal grand jury issued an indictment against Franz von Papen, Captain Hans Tauscher, Captain Karl Boy-Ed, Constantine Covani and Franz von Rintelen on charges of a plot to blow up the Welland Canal.[22][23][24] However, Papen was at the time safely on German soil, having been expelled from the US several months previously for alleged earlier acts of espionage and attempted sabotage.

Von Papen remained under indictment on these charges until he became Chancellor of Germany in 1932, at which time the charges were dropped.

Shipping season

The Welland Canal closes in winter (January–March) when ice or weather conditions become a hazard to navigation. The shipping season reopens in spring when the waters are once again safe. In 2007, the season opened on the earliest date ever, March 20, just hours ahead of the vernal equinox.

Facts and figures

Current canal

- Maximum vessel length: 225.5 m (740 ft)

- Maximum draft: 8.2 m (27 ft)

- Maximum above-water clearance: 35.5 m (116 ft)

- Elevation change between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie: 99.5 m (326 ft)

- Average transit time between the lakes: 11 hours

- Length of canal: 43.5 km (27.0 mi)

Increasing lock size

| Canal | First (1829) | Second (1848) | Third (1887) | Fourth (1932) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locks | 40 | 27 | 26 | 8 |

| Width (metres) | 6.7 | 8.1 | 13.7 | 24.4 |

| Length (metres) | 33.5 | 45.7 | 82.3 | 261.8 |

| Depth (metres) | 2.4 | 2.7 | 4.3 | 8.2 |

List of locks and crossings

Locks and crossings are numbered from north to south.

| Municipality | Lock or bridge number † | Crossing | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| St. Catharines | Lock 1 | 43°13′03″N 79°12′47″W / 43.217484°N 79.212992°W | |

| St. Catharines | Bridge 1 | Lakeshore Road (Regional Road 87) | |

| St. Catharines | Bridge 2 | Church Road (Now Linwell Road) | Never installed |

| St. Catharines | Lock 2 | 43°11′35″N 79°12′08″W / 43.193131°N 79.202178°W | |

| St. Catharines | Bridge 3A | Carlton Street (Regional Road 83) | Replaced original Bridge 3 (destroyed in accident) |

| St. Catharines | Bridge 4A | Garden City Skyway: Queen Elizabeth Way | |

| St. Catharines | Bridge 4 | Queenston Street (Regional Road 81) (former Highway 8) | also known as "Homer Lift Bridge" |

| St. Catharines | Lock 3 | 43°09′19″N 79°11′35″W / 43.155230°N 79.193058°W location of Welland Canal Information Centre | |

| St. Catharines | Bridge 5 | Glendale Avenue (Regional Road 89) | |

| St Catharines | Bridge 6 | Great Western Railway (Ontario) (now Canadian National Railway) |

|

| St Catharines | Lock 4 | twinned flight lock | |

| Thorold | Locks 5–6 | 43°08′03″N 79°11′31″W / 43.134283°N 79.191899°W twinned flight locks | |

| Thorold | Lock 7 | 43°07′24″N 79°11′38″W / 43.123446°N 79.193895°W southernmost lift over the Niagara Escarpment | |

| Thorold | Bridge 7 | Hoover Street | removed |

| Thorold | Bridge 8 | Niagara Central Railway (now Canadian National Railway) |

removed |

| Thorold | Thorold Tunnel, carries Highway 58 | ||

| Thorold | Bridge 9 | Ormond Street | removed |

| Thorold | Bridge 10 | Welland Railway (now Canadian National Railway) |

removed winter 1998 |

| Thorold | Bridge 11 | Canboro Road (Regional Road 20) (former Highway 20) | lowered prematurely on Windoc in 2001 |

| Thorold | Bridge 12 | Bridge Street (Regional Road 63) | destroyed by the Steelton in 1974 |

| Welland | Main Street Tunnel: (Highway 7146) | ||

| Welland | Townline Tunnel: Highway 58A and Canadian National Railway/Penn Central | ||

| Port Colborne | Bridge 19 | Main Street (Regional Road 3) Highway 3 | |

| Port Colborne | Lock 8 | 42°53′57″N 79°14′46″W / 42.899122°N 79.246166°W control lock | |

| Port Colborne | Bridge 19A | Mellanby Avenue (Regional Road 3A) | |

| Port Colborne | Bridge 20 | Buffalo and Lake Huron Railroad (now Canadian National Railway) |

removed winter 1997 |

| Port Colborne | Bridge 21 | Clarence Street |

Old alignment prior to Welland By-Pass relocation

| Municipality | Bridge Number † | Crossing | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Welland Recreational Waterway branches off from the Welland By-Pass at Port Robinson | |||

| Thorold | Canadian National Railway | built during the relocation | |

| Thorold | Highway 406 | built after the relocation | |

| Welland | Woodlawn Road (Regional Road 41) | built after the relocation | |

| Welland | Bridge 13 | East Main Street/West Main Street (Regional Road 27) | vertical lift bridge, counterweights removed 42°59′30″N 79°15′05″W / 42.99167°N 79.25139°W |

| Welland | Division Street (Regional Road 527) | built after the relocation | |

| Welland | Bridge 14 | Lincoln Street | rebuilt as fixed-span after the relocation 42°59′01″N 79°15′16″W / 42.98361°N 79.25444°W |

| Welland | Bridge 15 | Canada Southern Railway (Penn Central) | rare Baltimore truss swing bridge[25] 42°58′37″N 79°15′21″W / 42.97694°N 79.25583°W |

| Welland | Bridge 16 | Ontario Road/Broadway Avenue | rebuilt as fixed-span after the relocation, the new span located to the north of the original site of Bridge 16 42°58′25″N 79°15′21″W / 42.97361°N 79.25583°W |

| cut by western approaches to Townline Tunnel (Highway 58A and Canadian National Railway/Penn Central) | |||

| Welland | Bridge 17 | Canada Air-Line Railway (now Canadian National Railway) | vertical lift bridge, counterweights still present 42°56′57″N 79°15′00″W / 42.94917°N 79.25000°W |

| Welland | Bridge 18 | Forks Road | vertical lift bridge, towers and counterweights removed 42°56′50″N 79°14′58″W / 42.94722°N 79.24944°W |

| Welland Recreational Waterway merges with the Welland By-Pass at Ramey's Bend in Port Colborne | |||

† If assigned by the St. Lawrence Seaway Authority. The original bridges across the fourth canal were numbered in order. Numbering was not changed as bridges were removed.

Profile

The following illustration depicts the profile of the Welland Canal. The horizontal axis is the length of the canal. The vertical axis is the elevation of the canal segments above mean sea level.

See also

References

- ↑ "St. Lawrence Seaways System – Region Guide: Welland Canal Section" (Pdf).

- ↑ "The Welland Canal - Navigation, Locks, Distances, and Passage Information".

- ↑ Merrit, Jedediah (1875). Biography of the Hon. W. H. Merritt, M. P. St. Catherines: E. S. Leavenworth. p. 123. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Chambers, Melanie (26 February 2008). Frommer's Niagara Region. John Wiley & Sons. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-470-15324-6.

- ↑ "Three Boys Drowned When Steamer Broke Thru Gates Of Canal". Toronto World. June 21, 1912.

- ↑ "Windoc Bridge Accident". YouTube.

- ↑ "Transportation Safety Board of Canada - Marine Investigation Report M01C0054".

- ↑ "YouTube".

- ↑ http://www.niagarathisweek.com/news-story/5943018-port-colborne-bridge-still-closed-to-vehicles-after-collision-with-ship/

- ↑ https://www.vesselfinder.com/news/4388-Cargo-Ship-clips-bridge-in-Port-Colborne-Canada

- ↑ http://www.stcatharinesstandard.ca/2015/10/01/collision-closes-port-colborne-bridge

- ↑ http://portcolborne.ca/page/Bridge_Status

- ↑ http://www.wellandtribune.ca/2015/10/02/port-colborne-bridge-to-be-closed-for-months

- ↑ http://www.niagarathisweek.com/news-story/5943018-port-colborne-bridge-still-closed-to-vehicles-after-collision-with-ship/

- ↑ http://eriemedia.ca/status-of-bridge-19-port-colborne/

- ↑ http://portcolborne.ca/fileBin/library/Media%20Release%20-%20Port%20Colborne%20Bridge%20Closures.pdf

- ↑ "Canal has been terrorist target: Brock prof". Niagara This Week. February 26, 2010.

- ↑ http://wellandcanals.com/forum/index.php?topic=396.0

- ↑ Clark The Irish relations: trials of an immigrant tradition, p.121

- ↑ "Dynamite Luke among canal's terrorists". Welland Tribune. February 19, 2010.

- ↑ Clark The Irish relations: trials of an immigrant tradition, p.122

- ↑ "Tauscher, Figure In 1916 Plot, Dies. Acquitted of Charges That He Planned to Blow Up Welland Canal in World War. Served Krupp Interests. Ex-Aide of von Papen Had Arms Firms Here. Husband of Johanna Gadski, Singer". New York Times. September 6, 1941. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

Captain Hans Tauscher, former officer of the Imperial German Army, who was indicted with Franz von Papen during the World War but acquitted by a Federal jury of charges that he conspired to blow up the strategic Welland Canal, died here yesterday in St. Clare's Hospital. ...

- ↑ "Indict Von Papen As Canal Plotter. Federal Jury Names Recalled Attache and Four Others in Welland Conspiracy. One Name is Kept Secret. Captain, Tauscher, Fritzen, Covani, and Another Accused". New York Times. April 18, 1916.

Captain Franz von Papen, Military Attache of the German Embassy, who was recently, at the request of the United States Government, recalled to Germany, was indicted by a Federal Grand Jury yesterday as one of the heads of the alleged conspiracy that was hatched in this country in the first weeks of the war to destroy the Welland Canal, which forms the navigating link in Canadian territory between Lakes Erie and Ontario. ...

- ↑ "Welland Canal Case". Information Annual. 1917. p. 652. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Welland Railway Bridge".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Welland Canal. |

- Wellandcanals.ca – Detailed phototours of all Four Welland Canals

- Survey maps of the First and Second Welland Canals at Brock University

- Official Seaway Schedule Page

- Official Seaway Traffic Map Page

- "New Inland Canal Rivals Panama", February 1931, Popular Science

- The Old Welland Canals Field Guide

- Exploring the Old Welland Canals (Google map)

- Railway Maps (includes details of the Welland Realignment)

- The Welland Canal Section of the St. Lawrence Seaway (PDF)

- Has information about Niagara Region bridges, including many Welland Canal Bridges.

- Welland Public Library archive of canal history images & clippings

- Images from the Historic Niagara Digital Collections

- Art works from the collection of the Niagara Falls Public Library

- "Windoc Bridge Accident." Youtube, 2006-09-30.

- Al Miller, "Windoc Accident."

- The "Great Swivel Link": Canada's Welland Canal, a history of the canals published by the Champlain Society in 2000.

- Welland Canal Records Brock University Library Digital Repository

- Hamilton Merritt Welland Canal circular RG 506 Brock University Library Digital Repository

- Sykes fonds Welland Canal Scrapbook RG 341 Brock University Library Digital Repository

- Ivan S. Brookes fonds RG 182 Brock University Library Digital Repository

Coordinates: 43°09′20.00″N 79°11′37.50″W / 43.1555556°N 79.1937500°W