Crime in New York City

| New York City | |

| Crime rates (2014) | |

| Crime type | Rate* |

|---|---|

| Homicide: | 3.9 |

| Robbery: | 243.7 |

| Aggravated assault: | 376.5 |

| Total violent crime: | 624.1 |

| Burglary: | 224.8 |

| Larceny-theft: | 1,398.6 |

| Motor vehicle theft: | 98.8 |

| Arson: | n/a |

| Total property crime: | 1,722.2 |

| Notes * Number of reported crimes per 100,000 population. * New York City did not report arson statistics |

|

| Source: permanent dead link] FBI 2014 UCR data | |

Violent crime in New York City has been dropping since the mid-1990s[1][2] and, as of 2015, is lower than the national average for big cities.[3] In 2014, there were 328 homicides, the lowest number since at least 1963.[2][4] Crime rates spiked in the 1980s and early 1990s as the crack epidemic hit the city.[5][6] According to a 2015 ranking of 50 cities by The Economist, New York was the 10th overall safest major city in the world, as well as the 28th safest in personal safety.[7]

During the 1990s the New York City Police Department (NYPD) adopted CompStat, broken windows policing and other strategies in a major effort to reduce crime. The city's dramatic drop in crime has been attributed by criminologists to policing tactics, the end of the crack epidemic, and some have speculated more controversial ideas such as the legalization of abortion approximately 18 years previous[5][6] and the decline of lead poisoning of children.[8]

History

19th century

Organized crime has long been associated with New York City, beginning with the Forty Thieves and the Roach Guards in the Five Points in the 1820s.

In 1835, the New York Herald was established by James Gordon Bennett, Sr., who helped revolutionize journalism by covering stories that appeal to the masses including crime reporting. When Helen Jewett was murdered on April 10, 1836, Bennett did innovative on-the-scene investigation and reporting and helped bring the story to national attention.[9]

Peter Cooper, at request of the Common Council, drew up a proposal to create a police force of 1,200 officers. The state legislature approved the proposal which authorized creation of a police force on May 7, 1844, along with abolition of the nightwatch system.[10] Under Mayor William Havemeyer, the police force was reorganized and officially established on May 13, 1845 as the New York City Police Department (NYPD), with the city divided into three districts, with courts, magistrates, and clerks, and station houses set up.[10]

High-profile murders

Murder of Helen Jewett

Helen Jewett was an upscale New York City prostitute whose 1836 murder, along with the subsequent trial and acquittal of her alleged killer, Richard P. Robinson, generated an unprecedented amount of media coverage.[11]

Murder of Mary Rogers

The murder of Mary Rogers in 1841 was heavily covered by the press, which also put the spotlight on the ineptitude and corruption in the city's watchmen system of law enforcement.[9] At the time, New York City's population of 320,000 was served by an archaic force, consisting of one night watch, one hundred city marshals, thirty-one constables, and fifty-one police officers.[10]

Murder of Benjamin Nathan

Benjamin Nathan, patriarch of one of the earliest Sephardic Jewish families to emigrate to New York, was found bludgeoned to death in his rooms in the Fifth Avenue Hotel on the morning of July 28, 1870. Police initially suspected one of the family's servants, mostly Irish immigrants; later on Nathan's profligate son Washington was mentioned in the newspapers as a possible suspect (since Albert Cardozo, a relative by marriage, interfered in the investigation). However, no one was ever indicted and the case remains unsolved.[12]

Riots

1863 draft riots

The New York City draft riots in July 1863[13] were violent disturbances in New York City that were the culmination of working-class discontent with new laws passed by Congress that year to draft men to fight in the ongoing American Civil War. The riots remain the largest civil insurrection in American history, aside from the Civil War itself.[14]

President Abraham Lincoln was forced to divert several regiments of militia and volunteer troops from following up after the Battle of Gettysburg to control the city. The rioters were overwhelmingly working-class men, primarily ethnic Irish, resenting particularly that wealthier men, who could afford to pay a $300 ($5,555 in 2014 dollars) commutation fee to hire a substitute, were spared from the draft.[15][16]

Initially intended to express anger at the draft, the protests turned into a race riot, with white rioters, mainly but not exclusively Irish immigrants,[14] attacking blacks wherever they could be found. At least 11 blacks are estimated to have been killed. The conditions in the city were such that Major General John E. Wool, commander of the Department of the East, stated on July 16 that "martial law ought to be proclaimed, but I have not a sufficient force to enforce it."[17] The military did not reach the city until after the first day of rioting, when mobs had already ransacked or destroyed numerous public buildings, two Protestant churches, the homes of various abolitionists or sympathizers, many black homes, and the Colored Orphan Asylum at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue, which was burned to the ground.[18]

Other riots

In 1870, the Orange Riots were incited by Irish Protestants celebrating the Battle of the Boyne with parades through predominantly Irish Catholic neighborhoods. In the resulting police action, 63 citizens, mostly Irish, were killed.[19]

The Tompkins Square Riot occurred on January 13, 1874 when police violently suppressed a demonstration involving thousands of people in Tompkins Square Park.[20]

20th and 21st centuries

High-profile crimes include:

1900s–1950s

- April 14, 1903 — The dismembered and mutilated body of Benedetto Madonia, who had last been seen the day before eating with several high-ranking figures in the Morello crime family, the city's first dominant Mafia organization, is found in an East Village barrel, the most notorious of that era's Barrel Murders. After the NYPD arrested several members of the family tied to a local counterfeiting ring, Inspector George W. McClusky, hoping to compel their cooperation through public humiliation, arranged for them to be walked through the streets of Little Italy, in handcuffs to police headquarters, a forerunner of the perp walk that has since become a common practice in the city. It backfired, as the men were hailed as heroes by the Italian immigrant community they were paraded past. Charges against all defendants were later dropped for lack of evidence, and the killing remains unsolved.[21]

- June 25, 1906 – Stanford White is shot and killed by Harry Kendall Thaw at what was then Madison Square Gardens. The murder would soon be dubbed "The Crime of the Century".

- June 19, 1909 – The strangled body of Elsie Sigel, granddaughter of Civil War Union general Franz Sigel, 19, is found in a trunk in the Chinatown apartment of Leon Ling, a waiter at a Chinese restaurant, ten days after she was last seen leaving her parents' apartment to visit her grandmother. Evidence found in the apartment established that Ling and Sigel had been romantically involved, and he was suspected of the killing but never arrested. No other suspects have ever been identified.

- August 9, 1910 – Reformist Mayor William Jay Gaynor is shot in the throat in Hoboken, New Jersey by former city employee James Gallagher. He eventually dies in September 1913 from effects of the wound.

- July 4, 1914 – Lexington Avenue bombing: Four are killed and dozens injured when dynamite, believed to have been accumulated by anarchists for an attempt to blow up John D. Rockefeller's Tarrytown mansion, goes off prematurely in a seven-story apartment building at 1626 Lexington Avenue.[22]

- June 11, 1920 – Joseph Bowne Elwell, a prominent auction bridge player and writer, was shot in the head early in the morning in his locked Manhattan home. Despite intense media interest, the crime was never solved (one confession to police was dismissed because the man who made it was of dubious sanity). The case inspired the development of the locked-room murder subgenre of detective fiction, when Ellery Queen realized that the intense public fascination with the case indicated that there was a market for fictional takes on the story.

- September 16, 1920 – The Wall Street bombing kills 38 at "the precise center, geographical as well as metaphorical, of financial America and even of the financial world." Anarchists were suspected (Sacco and Vanzetti had been indicted just days before) but no one was ever charged with the crime.

- November 6, 1928 – Jewish gangster Arnold Rothstein, 46, an avid gambler best remembered for his alleged role fixing the 1919 World Series, died of gunshot wounds inflicted the day before during a Manhattan business meeting. He refused to identify his killer to police. A fellow gambler who was believed to have ordered the hit as retaliation for Rothstein's failure to pay a large debt from a recent poker game (Rothstein in turn claimed it had been fixed) was tried and acquitted. No other suspects have ever emerged.

- August 6, 1930 – The disappearance of Joseph Force Crater, an Associate Justice of the New York Supreme Court. He was last seen entering a New York City taxicab. Crater was declared legally dead in 1939. His mistress Sally Lou Ritz (22) disappeared a few weeks later.

- December 24, 1933 – Leon Tourian, 53, primate of the Eastern Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church in America, is stabbed to death by several armed men while performing Christmas Eve services. All were arrested and convicted the following summer. The killing was motivated by political divisions within the church; the ensuing schism persists.

- March 19, 1935 – The arrest of a shoplifter inflames racial tensions in Harlem and escalates to rioting and looting, with three killed, 125 injured and 100 arrested.[23]

- March 28, 1937 – Veronica Gedeon, 20, a model known for posing in lurid illustrations for pulp magazines, is brutally murdered along with her mother and a boarder in her mother's Long Island City home. Sculptor Robert George Irwin, who left a telltale soap sculpture at the scene, was eventually arrested after a nationwide manhunt fed by widespread media coverage of the case, said to be the most intense since the Stanford White murder, which capitalized by Gedeon's risque professional work. After doubts about his sanity surfaced during trial, he was sentenced to life in prison.

- November 16, 1940 – "Mad Bomber" George Metesky plants the first bomb of his 16-year campaign of public bombings.

- January 11, 1943 – Carlo Tresca, an Italian American labor leader who led opposition to Fascism, Stalinism and Mafia control of unions, was shot dead at a Manhattan intersection during the night. Given the enemies he had made and their propensity for violence, the list of potential suspects was long; however the investigation was incomplete and no one was ever officially named. Historians believe the mostly likely suspect was mobster Carmine Galante, later acting boss of the Bonanno family, seen fleeing the scene, who had likely acted on the orders of a Bonanno underboss and Fascist sympathizer Tresca had threatened to expose.[24]

- August 1, 1943 – A race riot erupts in Harlem after an African-American soldier is shot by the police and rumored to be killed. The incident touches off a simmering brew of racial tension, unemployment, and high prices to a day of rioting and looting. Several looters are shot dead and about 500 persons are injured and another 500 arrested.

- March 8, 1952 – A month after helping police find bank robber Willie Sutton, 24-year-old clothing salesman Arnold Schuster is shot fatally outside his Brooklyn home. An extensive investigation failed to identify any suspects, although police came to believe that either the Gambino crime family or Sutton's associates had ordered the hit. Schuster's family filed a lawsuit against the city, which led to a landmark ruling by the state's Court of Appeals that the government has a duty to protect anyone who cooperates with the police when asked to do so.

- October 25, 1957 — Mafia boss Albert Anastasia was shot dead while being shaved at a Manhattan barbershop. As with many organized-crime killings, it remains officially unsolved.

1960s

- January 27, 1962 — The French Connection drug bust nets 112 pounds (51 kg) of heroin hidden inside a car shipped from France, with an estimated street value of $112 million, the biggest drug haul in U.S. history at that point. The work of detectives Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso leading up to it was later the subject of The French Connection by Robin Moore, which formed the basis for the influential, Oscar-winning 1971 film of the same name.

- May 18, 1962 – Two NYPD detectives were killed in a gun battle with robbers at the Boro Park Tobacco store in Brooklyn, the first time two NYPD detectives died in the same incident since the 1920s. The resulting manhunt brings in the perpetrators, including Jerry Rosenberg, who after being spared the death penalty would become one of America's best-known jailhouse lawyers.[25] The case also led to controversy over the perp walk, in which freshly arrested suspects are paraded in front of the media: Rosenberg filed a federal lawsuit over prejudicial remarks made by a detective during his, and another detective, Albert Seedman, was briefly demoted in response to outrage over a picture of him holding up the head of the other suspect, Tony Dellernia, for photographers who missed the perp walk.

- August 28, 1963 – The Career Girls Murders: Emily Hoffert and Janet Wylie, two young professionals, are murdered in their Upper East Side apartment by an intruder. Richard Robles, a young white man, was ultimately apprehended in 1965 after investigators erroneously arrested and forced a false confession from a black man, George Whitmore, who was completely innocent of the crime. Although Whitmore was compelled to wrongfully spend many years incarcerated, he was eventually released after his innocence was established, while Robles remains in prison as of 2013.[26]

- March 13, 1964 – Kitty Genovese is stabbed 82 times in Kew Gardens, Queens by Winston Moseley. The crime is witnessed by numerous people, none of whom aid Genovese or call for help. The crime is noted by psychology textbooks in later years for its demonstration of the bystander effect, although an article published in the New York Times in February 2004 indicated that many of the popular conceptions of the crime were instead misconceptions.[27] Moseley died in prison in 2016.

- July 18, 1964 – Riots break out in Harlem in protest over the killing of a 15-year-old by a white NYPD officer. One person is killed and 100 are injured in the violence.

- February 21, 1965 – Black nationalist leader Malcolm X is assassinated at the Audubon Ballroom by three members of the Nation of Islam.

- April 7, 1967: Members of the Lucchese crime family, including Henry Hill and Tommy DeSimone, walked into the Air France cargo terminal at JFK airport around midnight and walked out with $420,000 in cash that had been exchanged overseas. The theft, which remained undiscovered for two days, was at the time the highest-valued cargo theft at the airport;[28] it has since been exceeded by the 1978 Lufthansa heist perpetrated by some of the same criminals, including Hill. Both are dramatized in the 1991 Martin Scorsese film GoodFellas, based on Hill's memoirs.

- October 8, 1967 – James "Groovy" Hutchinson, 21, an East Village hippie/stoner, and Linda Fitzpatrick, 18, a newly converted flower child from a wealthy Greenwich, Connecticut family, are found bludgeoned to death at 169 Avenue B, an incident dubbed "The Groovy Murders" by the press. Two drifters later plead guilty to the murders.[29]

- July 3, 1968 – A Bulgarian immigrant and Neo-Nazi, 42-year-old Angel Angelof, opens fire from a lavatory roof in Central Park, killing a 24-year-old woman and an 80-year-old man before being gunned down by police.[30]

- June 13, 1969 – Clarence 13X, founder of the Nation of Islam splinter group Five-Percent Nation, was shot and killed in the early morning hours in the lobby of his girlfriend's Harlem apartment building. The crime remains unsolved.

- June 28, 1969 – A questionable police raid on the Stonewall Inn, a Greenwich Village gay bar, is resisted by the patrons and leads to a riot. The event helps inspire the founding of the modern homosexual rights movement.

1970s

- March 6, 1970 – Greenwich Village townhouse explosion: Three members of the domestic terrorist group the Weathermen are killed when a nail bomb they were building accidentally explodes in the basement of a townhouse on 18 West 11th Street.[31]

- May 21, 1971 – Two NYPD officers, Waverly Jones and Joseph Piagentini, are gunned down in ambush by members of the Black Liberation Army in Harlem. The gunmen, Herman Bell and Anthony Bottom, still in prison as of 2012, were rearrested in jail in connection with the 1971 killing of a San Francisco police officer.[32]

- April 7, 1972 – Mobster Joe Gallo is gunned down at Umberto's Clam House in Little Italy. The incident serves as the inspiration for the Bob Dylan's epic "Joey" recorded in 1975.

- 1972 Harlem mosque incident: On April 14, two NYPD officers responded to an apparent call for assistance from a detective at a Harlem address that turned out to be a mosque used by the Nation of Islam. What happened when they got there is still unclear, but both officers were seriously beaten, and one, Philip Cardillo, was shot. He died of the wounds six days later. Political pressures on the administration of Mayor John Lindsay from the city's African-American community led to compromises that resulted in the incident never being fully investigated; Lindsay and police commissioner Patrick V. Murphy were notably absent from Cardillo's funeral, at which another high-ranking officer publicly resigned in protest. The incident alienated many rank and file police officers and had a lasting effect on racial tensions in the city.Louis 17X Dupree, director of the mosque's school, was eventually tried for Cardillo's murder. After the first jury deadlocked, he was acquitted at a second trial because of the compromised and incomplete evidence; he has subsequently served time in different Southern states on other charges. Officially the case remains unsolved; investigators who reopened the case in the late 2000s claim the FBI is withholding information about informants it had in the mosque at the time.

- August 22, 1972 – John Wojtowicz and Salvatore Natuarale hold up a Brooklyn bank for 14 hours, in a bid to get cash to pay for Wojtowicz's gay lover's sex change operation. The scheme fails when the cops arrive, leading to a tense 14-hour standoff. Natuarale is killed by the police at JFK Airport. The incident served as the basis for the 1975 film Dog Day Afternoon.

- December 1972 — The police department discloses that around 200 pounds (91 kg) of heroin, much of it seized in the French Connection busts a decade earlier, has been stolen from evidence lockers over a period of several months and replaced with cornstarch by someone who signed in under false names and nonexistent badge numbers. Several detectives were suspected of complicity in the thefts; in 2009 Brooklyn mobster Anthony Casso, serving 455 years in federal prison, intimated that he knew who had stolen the drugs.[33]

- January 3, 1973 – The body of 29-year-old teacher Roseann Quinn is discovered, with multiple stab wounds, is discovered in her Upper West Side apartment after she failed to show up for the first day of classes in the new year. John Wayne Wilson, a man she had picked up at nearby bar on New Year's Eve, was later arrested and charged with the murder, but killed himself in jail before he could be tried. The incident inspired the 1975 novel Looking for Mr. Goodbar, the source for the 1977 film of the same name starring Diane Keaton.

- April 28, 1973 — Clifford Glover, a 10-year-old African-American resident of Jamaica, Queens, was shot and killed by police officer Thomas Shea while running from an unmarked car which he thought was a robbery attempt. Shea was charged with murder, the first time an NYPD officer had been so charged for a killing in the line of duty in 50 years. He claimed that he saw a gun, a claim that was contradicted by the ballistic evidence that showed Glover had been shot from behind. Race riots broke out following his acquittal the following year.[34]

- January 24, 1975 – Fraunces Tavern, a historical site in lower Manhattan, is bombed by the FALN, killing 4 people and wounding more than 50.

- December 29, 1975 – A bomb explodes in the baggage claim area of the TWA terminal at LaGuardia Airport, killing 11 and injuring 74. The perpetrators were never identified.[35]

- July 29, 1976 – David Berkowitz (aka the "Son of Sam") kills one person and seriously wounds another in the first of a series of attacks that terrorized the city for the next year.

- November 25, 1976 – NYPD officer Robert Torsney fatally shoots unarmed 15-year-old Randolph Evans in Cypress Hills, Brooklyn. Torsney is found not guilty by reason of insanity the following year and is released from Queens' Creedmoor Psychiatric Center in 1979, only to be denied a disability pension.

- October 12, 1978 – Sid Vicious, former bassist of seminal English punk band the Sex Pistols, allegedly stabs his girlfriend Nancy Spungen to death in their room in the Hotel Chelsea. He died of a drug overdose before he could be tried.

- December 11, 1978 – Lufthansa heist: At the German airline's JFK Airport cargo terminal, an armed gang makes off with $5 million in cash and $875,000 in jewelry in the early hours of the morning. The well-planned robbery was at the time the largest cash theft ever in the United States, and remains the largest theft ever at the airport. It was masterminded by members of the Lucchese crime family, including Henry Hill and Tommy DeSimone, who had pulled off the Air France robbery at the airport nine years earlier. Tensions among the gang over how the money was to be divided and some members' failure to keep a low profile in the wake of the crime led to the deaths or disappearances of 10 of those involved in the next few months, many of them believed to have been killed or ordered by Lucchese soldier Jimmy Burke although no one suspected of being directly involved was ever arrested and charged (not least because many died first). The crime and its aftermath have been dramatized in the films The 10 Million Dollar Robbery, The Big Heist and GoodFellas, Martin Scorsese's 1991 adaptation of Hill's memoirs. In 2014 Vincent Asaro, a 78-year-old Bonnano family capo, was indicted on charges of receiving money from the robbery and conspiring in it; he was acquitted the following year, the only person ever tried in relation to the crime.

- May 25, 1979 – Six-year-old Etan Patz vanishes after leaving his SoHo apartment to walk to his school bus alone. Despite a massive search by the NYPD the boy is never found, and was declared legally dead in 2001.[36]

1980s

- January 4, 1980 – Three Manhattan men suspected of 60 break-ins were arrested by the police.

- March 14, 1980 – Ex-Congressman Allard Lowenstein is assassinated in his law offices at Rockefeller Center by Dennis Sweeney, a deranged ex-associate.[37]

- December 8, 1980 – Ex-Beatle John Lennon is murdered in front of his home in The Dakota.

- June 22, 1982 – Willie Turks, an African American 34-year-old MTA worker, is set upon and killed by a white mob in the Gravesend section of Brooklyn. Eighteen-year-old Gino Bova was convicted of second-degree manslaughter in 1983.

- September 15, 1983 – Michael Stewart is allegedly beaten into a coma by New York Transit Police officers. Stewart died 13 days later from his injuries at Bellevue Hospital. On November 24, 1985, after a six-month trial, six officers were acquitted on charges stemming from Stewart's death.[38]

- April 15, 1984 – Christopher Thomas, 34, murders two women and 8 children at 1080 Liberty Avenue in the East New York section of Brooklyn.[39]

- October 29, 1984 – 66-year-old Eleanor Bumpurs is shot and killed by police as they tried to evict her from her Bronx apartment. Bumpurs, who was mentally ill, was wielding a knife and had slashed one of the officers. The shooting provoked heated debate about police racism and brutality. In 1987 officer Stephen Sullivan was acquitted on charges of manslaughter and criminally negligent homicide stemming from the shooting.[40]

- December 2, 1984 – Caroline Rose Isenberg, a 23-year-old aspiring actress, was stabbed to death in the early morning hours after returning to her Upper West Side apartment from a Broadway show. Emmanuel Torres, the building custodian's son, was arrested at the end of the month and charged with the crime; he was convicted the following year and sentenced to life in prison. The case received considerable national media attention.

- December 22, 1984 – Bernhard Goetz shoots and seriously wounds four unarmed black men on a 2 train on the subway who he claimed were trying to rob him, generating weeks of headlines and many discussions about crime and vigilantism in the media.

- April 17, 1985 – Mark Davidson, a high school student, is arrested and tortured in Queens' 106th Precinct on drug dealing charges.

- June 12, 1985 – Edmund Perry, a returning graduate of Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire, is shot to death in Harlem by undercover officer Lee Van Houten after Perry and his brother, Jonah, attacked Van Houten to get money for a movie. Van Houten was acquitted the following month.

- December 16, 1985 – Gambino crime family boss Paul Castellano is shot dead in a gangland execution on East 46th Street in Manhattan.

- February 25, 1986 – 2 dead and 4 hurt including 3 police officers, in a shootout in the Bronx.

- July 7, 1986 – A deranged man, Juan Gonzalez, wielding a machete kills 2 and wounds 9 on the Staten Island Ferry. In 2000 Gonzalez was granted unsupervised leave from his residence at the Bronx Psychiatric Hospital.[41]

- August 26, 1986 – 18-year-old student Jennifer Levin is murdered by Robert Chambers in Central Park after the two had left a bar to have sex in the park. The case was sensationalized in the press and raised issues over victims' rights, as Chambers' attorney attempted to smear Levin's reputation to win his client's freedom.

- October 4, 1986 – CBS News anchorman Dan Rather is assaulted while walking along Park Avenue by two men, one of whom Rather reported kept asking him "Kenneth, what is the frequency?" as he did.[42] The mysterious question became a pop-culture catch phrase and inspired an R.E.M. song, which Rather joined the band with in performing on Late Night with David Letterman A man named William Tager, who apparently believed that Rather was secretly broadcasting messages to him, was identified as one of the assailants in 1997 (though not charged because the statute of limitations had expired) following his own conviction for killing an NBC stagehand.[43]

- November 19, 1986 – 20-year-old Larry Davis opens fire on NYPD officers attempting to arrest him in his sister's apartment in the Bronx. Six officers are wounded, and Davis eludes capture for the next 17 days, during which time he became something of a folk hero in the neighborhood. Davis was stabbed to death in jail in 2008.

- November 24, 1986 – Two Port Authority police officers and a holdup were seriously shot and wounded in a shootout at a Queens diner.

- December 20, 1986 – A white mob in Howard Beach, Queens, attacks three African-American men whose car had broken down in the largely white neighborhood. One of the men, Michael Griffith is chased onto Shore Parkway where he is hit and killed by a passing car. The killing prompted several tempestuous marches through the neighborhood led by Al Sharpton.

- July 9, 1987 – 12-year-old Jennifer Schweiger, a girl afflicted with Down syndrome, is abducted and murdered in Staten Island by a sex offender and suspected mass murderer, Andre Rand.

- November 2, 1987 – Joel Steinberg and his lover Hedda Nussbaum are arrested for the beating and neglect of their six-year-old adopted daughter Lisa Steinberg, who died two days later from her injuries. The case provoked outrage that did not subside when Steinberg was released from prison in 2004 after serving 15 years.

- February 26, 1988 – A gunman shot rookie NYPD officer Edward Byrne while he was alone in a patrol car monitoring a Jamaica street where a homeowner had reported violence and threats against his house. The blatant, deliberate nature of the killing resulted in widespread outrage, with President Ronald Reagan personally calling the Byrne family to offer condolences. Four men, apparently acting on the orders of a jailed drug dealer, were arrested within a week; all involved are serving lengthy prison sentences.

- December 21, 1988 – Thomas Pellagatti, 23, better known as drag queen Venus Xtravaganza, featured in the documentary film Paris is Burning, was found strangled under a Manhattan hotel bed. The autopsy established that he had been killed four days earlier. No suspects have ever been named.

- April 19, 1989 – Central Park jogger Trisha Meili is violently raped and beaten while jogging in Central Park. The crime is attributed to a group of young men who were practicing an activity the police called "wilding", with five of these teens convicted and jailed. In 2002, after the five had completed their sentences, Matias Reyes – a convicted rapist and murderer serving a life sentence for other crimes – confessed to the crime, after which DNA evidence proved the five teens innocent.

The Reverend Al Sharpton leading the first protest march over the death of Yusuf Hawkins in Bensonhurst, 1989.

The Reverend Al Sharpton leading the first protest march over the death of Yusuf Hawkins in Bensonhurst, 1989. - August 23, 1989 – Yusuf Hawkins, an African-American 16-year-old student, is set upon and murdered by a white mob in the Bensonhurst neighborhood of Brooklyn.[44]

1990s

- March 7, 1990 – 12-year-old Haitian immigrant David Opont is mugged and set on fire by a 14-year-old assailant, who remained anonymous because he was tried as a minor. The attack created an outpouring of support throughout the city for Opont who eventually recovered from his burns.[45]

- March 8, 1990 – The first of the copycat Zodiac Killer Heriberto Seda's eight shooting victims is wounded in an attack in Brooklyn. Between 1990 and 1993, Seda will wound 5 and kill 3 in his serial attacks. He is captured in 1996 and convicted in 1998.

- March 25, 1990 – Arson at the Happyland Social Club at 1959 Southern Boulevard in the East Tremont section of the Bronx kills 87 people unable to escape the packed dance club.[46]

- September 2, 1990 – Utah tourist Brian Watkins is stabbed to death in the Seventh Avenue – 53rd Street station by a gang of youths. Watkins was visiting New York with his family to attend the US Open Tennis tournament in Queens, when he was killed defending his family from a gang of muggers. The killing marked a low point in the record murder year of 1990 and led to an increased police presence in New York.[47]

- November 5, 1990 – Rabbi Meir Kahane, founder of the Jewish Defense League, is assassinated at the Marriott East Side Hotel at 48th Street and Lexington Avenue by El Sayyid Nosair.

- January 24, 1991 – Arohn Kee rapes and murders 13-year-old Paola Illera in East Harlem while she is on her way home from school. Her body is later found near the FDR Drive. Over the next eight years, Kee murders two more women before being arrested in February 1999. He is sentenced to three life terms in prison in January 2001.

- July 23, 1991 – The body of a four-year-old girl is found in a cooler on the Henry Hudson Parkway in Inwood, Manhattan. The identity of the child, dubbed "Baby Hope," is unknown until October 2013, when 52-year-old Conrado Juarez is arrested after confessing to killing the girl, his cousin Anjelica Castillo, and dumping her body.[48]

- August 19, 1991 – A Jewish automobile driver accidentally kills a seven-year-old African-American boy, thereby touching off the Crown Heights riots, during which an Australian Jew, Yankel Rosenbaum, was fatally stabbed by Lemrick Nelson.

- August 28, 1991 – A 4 train crashes just north of 14th Street – Union Square, killing 5 people. Motorman Robert Ray, who was intoxicated, fell asleep at the controls and was convicted of manslaughter in 1992.[49]

- February 26, 1992 – Two teens were shot to death by 15-year-old Khalil Sumpter inside Thomas Jefferson High School an hour before a scheduled visit by then mayor David Dinkins. Sumpter was paroled in 1998 at the age of 22.[50]

- March 11, 1992 – Manuel de Dios Unanue, a Cuban-born journalist who edited several Spanish-language newspapers, was shot to death at a Queens bar. Several men were later convicted in the murder, apparently carried out at the order of the Colombian Cali cartel on whose activities de Dios had reported extensively, the first time the cartel had murdered one of its opponents on American soil.

- December 17, 1992 – Patrick Daly, principal of P.S. 15 in Red Hook, Brooklyn, is killed in the crossfire of a drug-related shooting while looking for a pupil who had left his school. The school was later renamed the Patrick Daly school after the principal.[51]

- February 26, 1993 – A bomb planted by terrorists explodes in the World Trade Center's underground garage, killing six people and injuring over a thousand, as well as causing much damage to the basement. See: World Trade Center bombing

- December 7, 1993 – Colin Ferguson shoots 25 passengers, killing six, on a Long Island Rail Road commuter train out of Penn Station.

- March 1, 1994 – During the 1994 New York school bus shooting, Rashid Baz, a Lebanese-born Arab immigrant, opens fire on a van carrying members of the Lubavitch Hasidic sect of Jews driving on the Brooklyn Bridge. A 16-year-old student, Ari Halberstam later dies of his wounds. Baz was apparently acting out of revenge for the Cave of the Patriarchs massacre in Hebron, West Bank.[52]=

- August 31, 1994 – William Tager shoots and kills Campbell Theron Montgomery, a technician employed by NBC, outside of the stage of the Today show. Tager is also identified as one of possibly two men who assaulted CBS News anchor Dan Rather on Park Avenue in 1986.

- December 15, 1994 – Disgruntled computer analyst Edward J. Leary firebombs a 3 train with homemade explosives at 145th Street, injuring two teenagers. Six days later, he firebombs a crowded 4 train at Fulton Street, injuring over 40. Leary is sentenced to 94 years in prison for both attacks.[53]

- December 22, 1994 – Anthony Baez, a 29-year-old Bronx man, dies after being placed in an illegal chokehold by NYPD officer Francis X. Livoti. Livoti is sentenced to 7 and a half years in 1998 for violating Baez' civil rights.[54]

- November 30, 1995 – Rapper Randy Walker, 27, better known as Stretch, was shot and killed by the occupants of a vehicle passing his minivan in Queens Village, New York, shortly after midnight. No suspects have ever been identified, but it is often believed to be somehow related to his onetime colleague Tupac Shakur's later death, since it took place exactly one year after an apparent robbery attempt in Manhattan in which Shakur had been seriously injured.

- December 8, 1995 – A long racial dispute in Harlem over the eviction of an African-American record store-owner by a Jewish proprieter ends in murder and arson. 51-year-old Roland Smith, Jr., angry over the proposed eviction, set fire to Freddie's Fashion Mart on 125th Street and opened fire on the store's employees, killing 7 and wounding four. Smith also perished in the blaze.[55]

- March 4, 1996 – Second Avenue Deli owner Abe Lebewohl is shot and killed during a robbery. The murder of this popular deli owner and East Village fixture remains unsolved as of 2013.[56]

- June 4, 1996 – 22-year-old drifter John Royster brutally beats a 32-year-old female piano teacher in Central Park, the first in a series of attacks over a period of eight days. Royster would go on to brutally beat another woman in Manhattan, rape a woman in Yonkers and beat a woman, Evelyn Alvarez, to death on Park Avenue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. In 1998, Royster was sentenced to life in prison without parole.[57]

- March 17, 1996 — During an argument over drug debts, Michael Alig and Robert Riggs kill fellow "Club Kid" Andre Melendez, often known as "Angel" for the winged outfits he wore during the Club Kids' heyday. After keeping his body on ice in a bathtub for several days, Alig ultimately dismembered it and threw the parts in the Hudson River, where they washed up on Staten Island the next month. The pair were not arrested until October, and would eventually serve over a decade in prison after pleading guilty to manslaughter.[58]

- July 4, 1996 – A confrontation between a police officer and subway patron at the 167th Street station on the D train in the Bronx results in the shooting death of Nathaniel Levi Gaines, the patron. Officer Paolo Colecchia was convicted of homicide, the third time that has happened to a police officer in city history.

- February 5, 1997 – Ali Forney, 22, a homeless gay African American trans man who advocated for homeless LGBT youth, was found shot dead on a Harlem Street. The Ali Forney Center was established in his memory. No suspects have ever been named in the case.

- February 23, 1997 – Abu Ali Kamal, a 69-year-old Palestinian immigrant opens fire on the observation deck of the Empire State Building, killing one and wounding six before taking his own life.[59] In 2007 Kamal's daughter told the New York Daily News that the shooting was politically motivated.[60]

- May 30, 1997 – Jonathan Levin a Bronx teacher and son of former Time Warner CEO Gerald Levin, is robbed and murdered by his former student Corey Arthur.[61]

- August 9, 1997– Abner Louima is beaten and sodomized with a plunger at the 70th precinct house in Brooklyn by several NYPD officers led by Justin Volpe.

- November 7, 1997 – A Manhattan couple, Camden Sylvia, 36, and Michael Sullivan, 54, disappear from their loft at 76 Pearl Street in Manhattan after arguing with their landlord over a lack of heat in their apartment. The landlord, Robert Rodriguez, pleaded guilty to tax evasion, larceny and credit card fraud following the missing persons investigation. The couple is presumed dead; their bodies have never been found despite extensive searches.[62]

- January 3, 1999 – 32-year-old Kendra Webdale is killed after being pushed in front of an oncoming subway train at the 23rd Street station by Andrew Goldstein, a 29-year-old schizophrenic. The case ultimately led to the passage of Kendra's Law.

- February 4, 1999 – Unarmed African immigrant Amadou Bailo Diallo is shot and killed by four plainclothes police officers, sparking massive protests against police brutality and racial profiling.

- February 15, 1999 – Rapper Lamont Coleman, better known as Big L, is killed in a Harlem drive-by shooting. A friend, Gerard Woodley, was arrested and charged with the murder three months later but then released; no other suspects have ever been identified. Police believe the murder was either revenge for something Coleman's brother had done, or that he was mistaken for his brother.[63]

- March 8, 1999 – Amy Watkins, a 26-year-old social worker from Kansas who worked with battered women in the Bronx, is stabbed to death in a botched robbery near her home in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn. Her two assailants are sentenced to 25 years to life in prison.[64]

2000s

- March 24, 2000 – Patrick Dorismond is shot and killed by an NYPD officer in a case of mistaken identity during a drug bust.

- May 24, 2000 – Five employees of a Flushing, Queens, Wendy's restaurant are killed and two are seriously wounded during a robbery that netted the killers $2,400.

- May 10, 2001 – Actress Jennifer Stahl is killed with two other people in an armed robbery in her apartment above the Carnegie Deli in Manhattan. The victims were bound and shot point-blank in the head.[65]

- September 11, 2001 – Two jetliners destroy the two 110-story World Trade Center Twin Towers and several surrounding buildings in part of a coordinated terrorist attack, killing 2,606 people who were in the towers and on the ground. It is the deadliest mass-casualty incident in the city's history. That night, Polish immigrant Henryk Siwiak was shot dead in Bedford-Stuyvesant, where he had mistakenly gone to start a new job; due to scarce police resources at that time, the crime remains unsolved. It is the city's only official homicide for that day since the terrorist attack victims are not included in crime statistics.[66]

- October 30, 2002 – Two gunmen went into a Jamaica, recording studio and shot Jason Mizell, 37, better known as Jam Master Jay, a founding member of pioneering hip hop group Run-DMC, in the head at point-blank range; he died shortly thereafter.[67] While some suspects have been identified in the years since, no one has ever been prosecuted.

- April 24, 2003 – Romona Moore, a 21-year-old Hunter College student, disappeared after leaving home for a friend's house. The NYPD closed the case after two days. Her body was found on May 15, severely tortured; she had been kept alive for a considerable length of time after the case was closed. The two perpetrators were convicted in a second trial after a mistrial was declared following a courtroom attack by one of them. Moore's family sued the NYPD over what they felt was inadequate attention to the case compared to later cases involving young white women.[68]

- July 23, 2003 – Othniel Askew shoots to death political rival City Council member James E. Davis in the City Hall chambers of the New York City Council.

- October 15, 2003 — One of the Staten Island ferries crashes into the pier at St. George, killing 11. Pilot Richard Smith, who had nodded off due to the side effects of some over-the-counter painkillers he had taken, fled the scene for his home, where he was arrested after having survived two suicide attempts. He was later arrested, and pleaded guilty to manslaughter the next year, for which he was sentenced to 18 months in prison; the city's ferry director also served a year and a day after pleading guilty to the same charge.

- January 27, 2005 – Nicole duFresne, an aspiring actress, is shot dead in the Lower East Side section of Manhattan after being accosted by a gang of youths.[69]

- February 14, 2005 — Rashawn Brazell, 19, of Bushwick, is last seen leaving a subway station with two unidentified individuals,. Several days later plastic bags with parts of his dismembered body were found around the neighborhood. The case remains open and under investigation.

- June 16, 2005 – 15-year-old Phoenix Garrett is shot to death by 13-year-old L'mani Delima for allegedly selling bootleg Dipset Crew CDs. Delima is convicted of second degree murder and sentenced to nine years to life. On May 15, 2009, 33-year-old Carlos Thompson, accused of providing the gun and ordering the killing, is captured. He was sentenced in a plea deal to twelve years imprisonment and five years post-release supervision for manslaughter on June 9, 2010.[70][71][72]

- October 31, 2005 – Fashion journalist Peter Braunstein sexually assaults a co-worker while posing as a fireman, earning him the nickname of the "Fire Fiend" from the city's tabloids. He was arrested after leading officials on a multi-state manhunt. Braunstein was later sentenced to life and will be eligible for parole in 2023.

- January 11, 2006 – 7-year-old Nixzmary Brown dies after being beaten by her stepfather, Cesar Rodriguez, in their Brooklyn apartment. Rodriguez was convicted of first-degree manslaughter in March 2008.[73]

- February 25, 2006 – Criminology graduate student Imette St. Guillen is brutally tortured, raped, and killed in New York City after being abducted outside the Falls bar in the SoHo section of Manhattan. Bouncer Darryl Littlejohn is convicted of the crime and sentenced to life imprisonment.[74]

- April 1, 2006 – New York University (NYU) student Broderick Hehman is killed after being hit by a car in Harlem. Hehman was chased into the street by a group of black teens who allegedly shouted "get the white boy." The death of Hehman echoed the death of Michael Griffith 20 years earlier in Queens.[75]

- May 29, 2006 – Jeff Gross, founder of the Staten Island commune Ganas, is shot and wounded by former commune member Rebekah Johnson. Johnson was captured in Philadelphia on June 18, 2007 after being featured on America's Most Wanted.[76]

- June 13, 2006 – A homeless man named Kenny Alexis went on a stabbing spree in which he injured four people, including three tourists, across a 12-hour span in Manhattan.

- July 10, 2006 – 66-year-old Romanian immigrant Dr. Nicholas Bartha commits suicide by blowing up his townhouse at 34 East 62nd Street in Manhattan while in the basement of the building. Bartha chose to demolish his home rather than relinquish it to his ex-wife as ordered by the courts.[77]

- July 25, 2006 – Jennifer Moore, an 18-year-old student from New Jersey is abducted and killed after a night of drinking at a Chelsea bar. Her body is found outside a Weehawken motel. 35-year-old Draymond Coleman was convicted of the crime and sentenced to 50 years in 2010.[78]

- August 28, 2006 – Matthew Colletta, a 34-year-old man suffering from mental illness, goes on a shooting spree in Queens. One man is killed and five are wounded before Colletta is apprehended by the NYPD in Queens early the next morning.[79]

- October 8, 2006 – Michael Sandy, a 29-year-old man, is hit by a car on the Belt Parkway after being beaten by a group of white attackers. Sandy died of his injuries on October 13, 2006. The attack, which is being investigated as a hate crime hearkened back to the killing of Michael Griffith in 1986.[80]

Memorial to Sean Bell

Memorial to Sean Bell - November 25, 2006 – Four NYPD officers fire a combined 50 shots at a group of unarmed men in Jamaica, Queens, wounding two and killing 23-year-old Sean Bell. The case sparks controversy over police brutality and racial profiling.

- March 14, 2007 – 32-year-old David Garvin goes on a shooting rampage in Greenwich Village, killing a pizzeria employee and two auxiliary police officers before NYPD officers fatally shoot him.[81]

- July 9, 2007 – Rookie police officer Russel Timoshenko is shot five times while pulling over a stolen BMW in Crown Heights; he died five days later. A massive manhunt led to the arrest of three men a week later in Pennsylvania, who were eventually convicted of the crime. All three were carrying guns obtained illegally, which led Mayor Michael Bloomberg and other city officials to stiffen city ordinances on illegal firearm possession and seek tighter gun-control laws at the state and national level.

- February 12, 2008 – Psychologist Kathryn Faughey is brutally murdered in her Manhattan office by a mentally ill man whose intended victim was a psychiatrist in the same practice.[82]

- December 2, 2008 – 25-year-old aspiring dancer Laura Garza disappears after leaving a Manhattan nightclub with a sex offender named Michael Mele. Her remains are found in Olyphant, Pennsylvania in April 2010. On the first day of his trial in January 2012, Mele admits to killing Garza and pleads guilty to first degree manslaughter.[83]

- March 20, 2009 – WABC-AM radio personality George Weber was found stabbed to death in his Brooklyn apartment during an apparent robbery. A teenage boy who had answered an Internet ad Weber placed was later convicted of the crime.

2010s

- July 22, 2010 – Five members of the Jones family were killed in an apparent case of murder-suicide arson in the Port Richmond section of Staten Island.[84]

- February 11, 2011 – Maksim Gelman, 23 years old, goes on a 28-hour rampage killing 5 and wounding 6 others throughout Brooklyn and Manhattan. He is sentenced to life imprisonment.[85]

- July 13, 2008 – The body of 8-year-old Leiby Kletzky is found dismembered in two locations in Brooklyn after he was allegedly murdered by 35-year-old Eddie Low.[86]

- September 5, 2011 – Over 67 separate shootings take place in Manhattan, Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx during a particularly violent Labor Day weekend leaving 13 dead. One of the shootings took place just blocks from Mayor Bloomberg and which 8 police officers fired over 70 shots, with two of them being injured in the shootout.

- December 17, 2011 – Deloris Gillespie, 73, was burned alive in her Prospect Heights apartment elevator by Jerome Isaac, 47. Isaac was sentenced to a minimum of 50 years in prison in 2012.[87]

- July 31, 2012 – Ramona Moore, 35, disappears after reportedly arguing with Nasean Bonie, her superintendent over the rent on her apartment near Crotona Park in the Bronx. Over the next two years, police eventually developed enough evidence to charge him with her murder despite the absence of her body. It was found in Orange County in 2015, the week before his trial, which would have been the first murder prosecution without a body in the borough's history, was to start.[88] In 2016, a jury acquitted Bonie, already serving time for assaulting his wife, of the murder charge but convicted him of manslaughter; he was sentenced to 25 years in prison.

- August 24, 2012 – Jeffrey Johnson, 58, shot and killed a former co-worker before being shot and killed by police officers outside the Empire State Building. A total of 11 people, including the gunman, were shot.[89]

- October 25, 2012 – Lucia and Leo Krim were allegedly stabbed to death by their babysitter in their Upper West Side apartment.

- October 26, 2013 – Five people, including four children, are stabbed to death in an apartment in Borough Park, Brooklyn.[90]

- June 1, 2014 - Prince Joshua "PJ" Avitto, 6, was fatally stabbed, and a 7-year-old girl was injured by a man in an elevator at an East New York apartment building. A 27-year-old was arrested.[91][92]

- July 17, 2014 – Eric Garner, a 43-year-old African-American man on Staten Island, died after a chokehold was applied to him during a confrontation with police over selling untaxed cigarettes; the incident, captured on cellphone video, showed that the asthmatic Garner had repeatedly called out "I can't breathe!" The case attracted national attention as it occurred at the same time as the equally racially tinged shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. A grand jury declined to indict Daniel Pantaleo, the officer involved.[93]

- November 20, 2014 – A 28-year-old Brooklyn man, Akai Gurley, is shot dead by rookie NYPD officer Peter Liang during a "vertical patrol" on the staircases of Louis H. Pink housing projects in East New York. Liang was convicted of manslaughter in February 2016; he is currently appealing the verdict.[94]

- December 20, 2014 – A gunman kills two NYPD officers and then himself in Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.

- May 2, 2015 – Police officers Brian Moore and Erik Jansen are shot in Queens by Demetrius Blackwell after they ask him to stop while walking down the street; Moore died in the hospital two days later. Blackwell was soon arrested and is facing murder charges.

- May 17, 2015 – Rapper Chinx and another are wounded in a drive-by shooting along Queens Boulevard; he dies at the hospital later. The killing remains unsolved.

- January 2016 - At least six slashing attacks targeting random strangers occur at various subway platforms throughout the city. At least two suspects have been arrested in connection with the incidents.[95]

- September 2016 - 31 people are injured in a pressure cooker bombing in Chelsea, Manhattan. A bombing occurred earlier that day in Seaside Park, New Jersey, and no one was injured as a result. A suspect in both bombings was arrested the following day after a shootout in Linden, New Jersey that left him and three police officers injured.[96]

Notable recent crime trends

Wall Street frauds

Wall Street has become synonymous with financial interests, often used negatively.[97] During the subprime mortgage crisis from 2007 to 2010, Wall Street financing was blamed as one of the causes, although most commentators blame an interplay of factors. The U.S. government with the Troubled Asset Relief Program bailed out the banks and financial backers with billions of taxpayer dollars, but the bailout was often criticized as politically motivated,[97] and was criticized by journalists as well as the public. Analyst Robert Kuttner in the Huffington Post criticized the bailout as helping large Wall Street firms such as Citigroup while neglecting to help smaller community development banks such as Chicago's ShoreBank.[97] One writer in the Huffington Post looked at FBI statistics on robbery, fraud, and crime and concluded that Wall Street was the "most dangerous neighborhood in the United States" if one factored in the $50 billion fraud perpetrated by Bernie Madoff.[98] When large firms such as Enron, WorldCom and Global Crossing were found guilty of fraud, Wall Street was often blamed,[99] even though these firms had headquarters around the nation and not in Wall Street. Many complained that the resulting Sarbanes-Oxley legislation dampened the business climate with regulations that were "overly burdensome."[100] Interest groups seeking favor with Washington lawmakers, such as car dealers, have often sought to portray their interests as allied with Main Street rather than Wall Street, although analyst Peter Overby on National Public Radio suggested that car dealers have written over $250 billion in consumer loans and have real ties with Wall Street.[101] When the United States Treasury bailed out large financial firms, to ostensibly halt a downward spiral in the nation's economy, there was tremendous negative political fallout, particularly when reports came out that monies supposed to be used to ease credit restrictions were being used to pay bonuses to highly paid employees.[102] Analyst William D. Cohan argued that it was "obscene" how Wall Street reaped "massive profits and bonuses in 2009" after being saved by "trillions of dollars of American taxpayers' treasure" despite Wall Street's "greed and irresponsible risk-taking."[103] Washington Post reporter Suzanne McGee called for Wall Street to make a sort of public apology to the nation, and expressed dismay that people such as Goldman Sachs chief executive Lloyd Blankfein hadn't expressed contrition despite being sued by the SEC in 2009.[104] McGee wrote that "Bankers aren't the sole culprits, but their too-glib denials of responsibility and the occasional vague and waffling expression of regret don't go far enough to deflect anger."[104]

But chief banking analyst at Goldman Sachs, Richard Ramsden, is "unapologetic" and sees "banks as the dynamos that power the rest of the economy."[105] Ramsden believes "risk-taking is vital" and said in 2010:

You can construct a banking system in which no bank will ever fail, in which there's no leverage. But there would be a cost. There would be virtually no economic growth because there would be no credit creation. – Richard Ramsden of Goldman Sachs, 2010.[105]

Others in the financial industry believe they've been unfairly castigated by the public and by politicians. For example, Anthony Scaramucci reportedly told President Barack Obama in 2010 that he felt like a piñata, "whacked with a stick" by "hostile politicians".[105]

The financial misdeeds of various figures throughout American history sometimes casts a dark shadow on financial investing as a whole, and include names such as William Duer, Jim Fisk and Jay Gould (the latter two believed to have been involved with an effort to collapse the U.S. gold market in 1869) as well as modern figures such as Bernard Madoff who "bilked billions from investors".[106]

In addition, images of Wall Street and its figures have loomed large. The 1987 Oliver Stone film Wall Street created the iconic figure of Gordon Gekko who used the phrase "greed is good", which caught on in the cultural parlance.[107] According to one account, the Gekko character was a "straight lift" from the real world junk-bond dealer Michael Milken,[99] who later pleaded guilty to felony charges for violating securities laws. Stone commented in 2009 how the movie had had an unexpected cultural influence, not causing them to turn away from corporate greed, but causing many young people to choose Wall Street careers because of that movie.[107] A reporter repeated other lines from the film:

| “ | I’m talking about liquid. Rich enough to have your own jet. Rich enough not to waste time. Fifty, a hundred million dollars, Buddy. A player. – lines from the script of Wall Street[107] | ” |

Wall Street firms have however also contributed to projects such as Habitat for Humanity as well as done food programs in Haiti and trauma centers in Sudan and rescue boats during floods in Bangladesh.[108]

Late 20th century trends

Freakonomics authors Steven Levitt and Steven Dubner attribute the drop in crime to the legalization of abortion in the 1970s, as they suggest that many would-be neglected children and criminals were never born.[109] On the other hand, Malcolm Gladwell provides a different explanation in his book The Tipping Point; he argues that crime was an "epidemic" and a small reduction by the police was enough to "tip" the balance.[110] Another theory is that widespread exposure to lead pollution from automobile exhaust, which can lower intelligence and increase aggression levels, incited the initial crime wave in the mid-20th century, most acutely affecting heavily trafficked cities like New York. A strong correlation was found demonstrating that violent crime rates in New York and other big cities began to fall after lead was removed from American gasoline in the 1970s.[111]

Gang violence

In the 20th century, notorious New York-based mobsters Arnold Rothstein, Meyer Lansky, and Lucky Luciano made headlines. The century's later decades are more famous for Mafia prosecutions (and prosecutors like Rudolph Giuliani) than for the influence of the Five Families.

Violent gangs such as the Black Spades and the Westies influenced crime in the 1970s.

The Bloods, Crips and MS-13 gangs of Los Angeles arrived in the city in the 1980s, but gained notoriety when they appeared on Rikers Island in 1993 to fight off the already established Latin Kings gang.

Chinese gangs were also prominent in Chinatown, Manhattan, notably Ghost Shadows and Flying Dragons.

Subway crime

Crime on the New York City Subway reached a peak in the late 1970s and early 1980s, with the city's subway having a crime rate higher than that of any other mass transit system in the world.[112] As of 2011, the subway has a record low crime rate, as crime started dropping in the '90s, a trend that continues today.[113][114]

Various approaches have been used to fight crime. A 2012 initiative by the MTA to prevent crime is to ban people who commit one in the subway system from entering it for a certain length of time.[115]

In the 1960s, mayor Robert Wagner ordered an increase in the Transit Police force from 1,219 to 3,100 officers. During the hours at which crimes most frequently occurred (between 8:00 p.m. and 4:00 a.m.), the officers went on patrol in all stations and trains. In response, crime rates decreased, as extensively reported by the press.[116]

However, as a consequence of the city's 1976 fiscal crisis, service had become poor and crime had gone up, with crime being announced on the subway almost every day. Additionally, there were 11 "crimes against the infrastructure" in open cut areas of the subway in 1977, where TA staff were injured, some seriously. There were other rampant crimes as well. For example, in the first two weeks of December 1977, "Operation Subway Sweep" resulted in the arrest of over 200 robbery suspects. Passengers were afraid of crime, fed up with long waits for trains that were shortened to save money, and upset over the general malfunctioning of the system. The subway also had many dark subway cars.[112] Further compounding the issue, on July 13, 1977, a blackout cut off electricity to most of the city and to Westchester.[112] Due to a sudden increase of violent crimes on the subway in the last week of 1978, police statistics about crime in the subway were being questioned. In 1979, six murders on the subway occurred in the first two months of the year, compared to nine during the entire previous year. The IRT Lexington Avenue Line was known to be frequented by muggers, so in February 1979, a group headed by Curtis Sliwa began unarmed patrols of the 4 train during the night time, in an effort to discourage crime. They were known as the Guardian Angels, and would eventually expand their operations into other parts of the five boroughs. By February 1980, the Guardian Angels' ranks numbered 220.[117]

In March 1979, Mayor Ed Koch asked the city's top law enforcement officials to devise a plan to counteract rising subway violence and to stop insisting that the subways were safer than the streets. Two weeks after Koch's request, top TA cops were publicly requesting Transit Police Chief Sanford Garelik's resignation because they claimed that he had lost control of the fight against subway crime. Finally, on September 11, 1979, Garelik was fired, and replaced with Deputy Chief of Personnel James B. Meehan, reporting directly to City Police Commissioner Robert McGuire. Garelik continued in his role of chief of security for the MTA.[112] By September 1979, around 250 felonies per week (or about 13,000 that year) were being recorded on the subway, making the crime rate the most of any other mass transit network anywhere in the world. Some police officers supposedly could not act upon quality of life crimes, and were only to look for violent crimes. Among other problems the following were included:

MTA police radios and New York City Police Department radios transmitted at different frequencies, so they could not coordinate with each other. Subway patrols were also adherent to tight schedules, and felons quickly knew when and where police would make patrols. Public morale of the MTA police was low at the time. so that by October 1979, additional decoy and undercover units were deployed in the subway.[112]

Meehan had claimed to be able to, along with 2.3 thousand police officers, "provide sufficient protection to straphangers", but Sliwa had brought a group together to act upon crime, so that between March 1979 and March 1980, felonies per day dropped from 261 to 154. However, overall crime grew by 70% between 1979 and 1980.[118]

On the IRT Pelham Line in 1980, a sharp rise in window-smashing on subway cars caused $2 million in damages; it spread to other lines during the course of the year. When the broken windows were discovered in trains that were still in service, they needed to be taken out of service, causing additional delays; in August 1980 alone, 775 vandalism-related delays were reported.[119] Vandalism of subway cars, including windows, continued through the mid-1980s; between January 27 and February 2, 1985, 1,129 pieces of glass were replaced on subway cars on the 1, 6, CC, E, and K trains.[120] Often, bus transfers, sold on the street for 50 cents, were also sold illegally, mainly at subway-to-bus transfer hubs.[121] Mayor Koch even proposed to put a subway court in the Times Square subway station to speed up arraignments, as there were so many subway-related crimes by then. Meanwhile, high-ranking senior City Hall and transit officials considered raising the fare from 60 to 65 cents to fund additional transit police officers, who began to ride the subway during late nights (between 8 p.m. and 4 a.m.) owing to a sharp increase in crime in 1982. Operation High Visibility, commenced in June 1985, had this program extended to 6 a.m., and a police officer was to be present on every train in the system during that time.[122]

On January 20, 1982, MTA Chairman Richard Ravitch told the business group Association for a Better New York, that he would not let his teenage sons ride the subway at night, and that even he, as the subway chairman, was nervous riding the trains.[123] The MTA began to discuss how the issue could be the ridership issue could be fixed, but by October 1982, mostly due to fears about transit crime, poor subway performance and some economic factors, ridership on the subway was at extremely low levels matching 1917 ridership.[124] Within less than ten years, the MTA had lost around 300 million passengers, mainly because of fears of crime. In July 1985, the Citizens Crime Commission of New York City published a study showing this trend, fearing the frequent robberies and generally bad circumstances.[125] As a result, the Fixing Broken Windows policy, which proposed to stop large-profile crimes by prosecuting quality of life crimes, was implemented.[126][127] Along this line of thinking, the MTA began a five-year program to eradicate graffiti from subway trains in 1984.[128]

To attract passengers, the TA tried to introduce the “Train to the Plane”, a service staffed by a transit police officer 24/7. This was discontinued in 1990 due to low ridership and malfunctioning equipment.

In 1989, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority asked the transit police (then located within the NYCTA) to focus on minor offenses such as fare evasion. In the early nineties, the NYCTA adopted similar policing methods for Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal. When in 1993, Mayor Rudy Giuliani and Police Commissioner Howard Safir were elected to official positions, the Broken Windows strategy was more widely deployed in New York under the rubrics of "zero tolerance" and "quality of life". Crime rates in the subway and city dropped,[129] prompting New York Magazine to declare "The End of Crime as We Know It" on the cover of its edition of August 14, 1995. Giuliani's campaign credited the success to the zero tolerance policy.[130] The extent to which his policies deserve the credit is disputed.[131] Incoming New York City Police Department Commissioner William J. Bratton and author of Fixing Broken Windows, George L. Kelling, however, stated the police played an "important, even central, role" in the declining crime rates.[132] The trend continued and Giuliani's successor, Michael Bloomberg, stated in a November 2004 press release that "Today, the subway system is safer than it has been at any time since we started tabulating subway crime statistics nearly 40 years ago."[133]

Child sexual abuse in religious institutions

Two cases in 2011 – those of Bob Oliva and Ernie Lorch – have both centered in highly ranked youth basketball programs sponsored by churches of different denominations. In early 2011, Oliva, a long-time basketball coach at Christ The King Regional High School, was accused of two cases of child sexual abuse.[134]

Also, sexual abuse in Brooklyn's Haredi Jewish community has been common.

In Manhattan, Father Bruce Ritter, founder of Covenant House, was forced to resign in 1990 after accusations that he had engaged in financial improprieties and had engaged in sexual relations with several youth in the care of the charity.[135]

In December 2012, the President of the Orthodox Jewish Yeshiva University apologized over allegations that two rabbis at the college’s high school campus abused boys there in the late 1970s and early ’80s.[136][137]

Nightlife legislation

In New York City, legislation was enacted in 2006, affecting many areas of nightlife. This legislation was in response to a number of murders which occurred in the New York City area, some involving nightclubs and bouncers. The city council introduced four pieces of legislation to help combat these problems, including Imette's Law, which required stronger background checks for bouncers. Among the legislative actions taken were the requirement of ID scanners, security cameras, and independent monitors to oversee problem establishments.

It also enacted the following plan:

- Create a city Office of Nightlife Affairs.

- Find ways to get more cops to patrol outside clubs and bars.

- Combat underage drinking and the use of fake IDs.

- Foster better relationship among club owners, the NYPD and the New York State Liquor Authority

- Raise age limit for admittance into a club or bar from 16 to 18 or 21.

- Develop a public-awareness campaign urging patrons to be safe at night.

- Examine zoning laws to help neighborhoods that are flooded with clubs and bars.

A new guideline booklet, NYPD and Nightlife Association Announce “Best Practices,[138] was unveiled on October 18, 2007. This voluntary rule book included a 58-point security plan drafted in part by the New York Nightlife Association, was further recommended by Police Commissioner Ray Kelly and Speaker Christine Quinn. Security measures included cameras outside of nightclub bathrooms, a trained security guard for every 75 patrons and weapons searches for everyone, including celebrities entering the clubs. The new regulation resulted in stricter penalties for serving underage persons.[139][140][141]

The Club Enforcement Initiative was created by the NYPD in response to what it referred to as "a series of high-profile and violent crimes against people who visited city nightclubs this year", mentioning the July 27 rape and murder of Jennifer Moore. One article discussed the dangers of police work and undercover investigations.[142]

In August 2006, the New York City Council started initiatives to correct the problems highlighted by the deaths of Moore and St. Guillen.[143][144] There was also discussions about electronic I.D. scanners. Quinn reportedly threatened to revoke the licenses of bars and clubs without scanners.[145]

In September 2011, the NYPD Nightlife Association updated their Safety Manual Handbook. There is now a section on counterterrorism; this addition came after the planned terrorist attacks on certain bars and clubs worldwide.[146]

Administration

Mayors

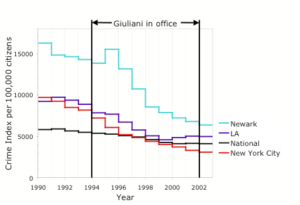

Crime in New York City was high in the 1980s during the Mayor Edward I. Koch years, as the crack epidemic hit New York City, and peaked in 1990,[1] the first year of Mayor David Dinkins' administration (1990–1994). During the administration of Mayor Rudolph Giuliani (1994–2002), there was a precipitous drop in crime in his first term, continuing at a slower rate in both his second term and under Mayor Michael Bloomberg (2002–2014).

Scholars differ on the causes of the precipitous decline in crime in New York City (which also coincided with a nationwide drop in crime which some have termed the "Great American Crime Decline").[147] In a 2007 paper, economist Jessica Reyes attributes a 56% drop in nationwide violent crime in the 1990s to the removal of lead (a neurotoxin that causes cognitive and behavioral problems) from gasoline.[147] The Brennan Center for Justice has estimated that between 0-5% of the drop in crime in the 1990s may be attributed to higher employment; 5-10% of the drop may be attributed to income growth; and 0-10% of the drop from increased hiring of police officers.[147] Economists Steven Levitt and John J. Donohue III argue that the drop in crime in New York City, as in the United States generally, to the legalization of abortion following Roe v. Wade (see legalized abortion and crime effect).[147]

David Dinkins

Under David Dinkins's Safe Streets, Safe Cities program, crime in New York City decreased more dramatically and more rapidly, both in terms of actual numbers and percentage, than at any time in modern New York City history.[148] The rates of most crimes, including all categories of violent crime, made consecutive declines during the last 36 months of his four-year term, ending a 30-year upward spiral and initiating a trend of falling rates that continued beyond his term.[149] Despite the actual abating of crime, Dinkins was hurt by the perception that crime was out of control during his administration.[150][151] Dinkins also initiated a hiring program that expanded the police department nearly 25%. The New York Times reported, "He obtained the State Legislature’s permission to dedicate a tax to hire thousands of police officers, and he fought to preserve a portion of that anticrime money to keep schools open into the evening, an award-winning initiative that kept tens of thousands of teenagers off the street."[151][152]

Rudy Giuliani

In Rudolph Giuliani's first term as mayor the New York City Police Department, under Giuliani appointee Commissioner Bill Bratton, adopted an aggressive enforcement and deterrence strategy based on James Q. Wilson's Broken Windows research. This involved crackdowns on relatively minor offenses such as graffiti, turnstile jumping, and aggressive "squeegeemen," on the principle that this would send a message that order would be maintained and that the city would be "cleaned up."

At a forum three months into his term as mayor, Giuliani mentioned that freedom does not mean that "people can do anything they want, be anything they can be. Freedom is about the willingness of every single human being to cede to lawful authority a great deal of discretion about what you do and how you do it".[153]

Giuliani also directed the New York City Police Department to aggressively pursue enterprises linked to organized crime, such as the Fulton Fish Market and the Javits Center on the West Side (Gambino crime family). By breaking mob control of solid waste removal, the city was able to save businesses over $600 million.

One of Bratton's first initiatives was the institution in 1994 of CompStat, a comparative statistical approach to mapping crime geographically in order to identify emerging criminal patterns and chart officer performance by quantifying apprehensions. The implementation of CompStat gave precinct commanders more power, based on the assumption that local authorities best knew their neighborhoods and thus could best determine what tactics to use to reduce crime. In turn, the gathering of statistics on specific personnel aimed to increase accountability of both commanders and officers. Critics of the system assert that it instead creates an incentive to underreport or otherwise manipulate crime data.[154] The CompStat initiative won the 1996 Innovations in Government Award from the Kennedy School of Government.[155]

Bratton was featured on the cover of Time Magazine in 1996 rather than Giuliani.[156] Giuliani forced Bratton out of his position after two years, in what was generally seen as a battle of two large egos in which Giuliani was unable to accept Bratton's celebrity.[157][158]

Giuliani continued to highlight crime reduction and law enforcement as central missions of his mayoralty throughout both terms. These efforts were largely successful.[160] However, concurrent with his achievements, a number of tragic cases of abuse of authority came to light, and numerous allegations of civil rights abuses were leveled against the NYPD. Giuliani's own Deputy Mayor, Rudy Washington, alleged that he had been harassed by police on several occasions. More controversial still were several police shootings of unarmed suspects,[161] and the scandals surrounding the sexual torture of Abner Louima and the killing of Amadou Diallo. In a case less nationally publicized than those of Louima and Diallo, unarmed bar patron Patrick Dorismond was killed shortly after declining the overtures of what turned out to be an undercover officer soliciting illegal drugs. Even while hundreds of outraged New Yorkers protested, Giuliani staunchly supported the New York City Police Department, going so far as to take the unprecedented step of releasing Dorismond's "extensive criminal record" to the public,[162] for which he came under wide criticism. While many New Yorkers accused Giuliani of racism during his terms, former mayor Ed Koch defended him as even-handedly harsh: "Blacks and Hispanics ... would say to me, 'He's a racist!' I said, 'Absolutely not, he's nasty to everybody'."[163]

The amount of credit Giuliani deserves for the drop in the crime rate is disputed. He may have been the beneficiary of a trend already in progress. Crime rates in New York City started to drop in 1991 under previous mayor David Dinkins, three years before Giuliani took office.[160] Under Dinkins's Safe Streets, Safe Cities program, crime in New York City decreased more dramatically and more rapidly, both in terms of actual numbers and percentage, than at any time in modern New York City history.[164] The rates of most crimes, including all categories of violent crime, made consecutive declines during the last 36 months of Dinkins's four-year term, ending a 30-year upward spiral.[150] A small but significant nationwide drop in crime also preceded Giuliani's election, and continued throughout the 1990s. Two likely contributing factors to this overall decline in crime were federal funding of an additional 7,000 police officers and an improvement in the national economy. But many experts believe changing demographics were the most significant cause.[165] Some have pointed out that during this time, murders inside the home, which could not be prevented by more police officers, decreased at the same rate as murders outside the home. Also, since the crime index is based on the FBI crime index, which is self-reported by police departments, some have alleged that crimes were shifted into categories that the FBI does not quantify.[166]

According to some analyses, the crime rate in New York City fell even more in the 1990s and 2000s than nationwide and therefore credit should be given to a local dynamic: highly focused policing. In this view, as much as half of the reduction in crime in New York in the 1990s, and almost all in the 2000s, is due to policing.[167] Opinions differ on how much of the credit should be given to Giuliani; to Bratton; and to the current Police Commissioner, Ray Kelly, who had previously served under Dinkins and criticized aggressive policing under Giuliani.[168]