Dupuytren's contracture

| Dupuytren's contracture | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dupuytren's contracture of the ring finger | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | rheumatology |

| ICD-10 | M72.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 728.6 |

| OMIM | 126900 |

| DiseasesDB | 4011 |

| MedlinePlus | 001233 |

| eMedicine | med/592 orthoped/81 plastic/299 pmr/42 derm/774 |

| Patient UK | Dupuytren's contracture |

| MeSH | D004387 |

Dupuytren's contracture (also known as Dupuytren's disease, or by the slang term "Viking disease")[1] is a flexion contracture of the hand due to a palmar fibromatosis,[2] in which the fingers bend towards the palm and cannot be fully extended (straightened). It is an inherited proliferative connective tissue disorder that involves the hand's palmar fascia.[3] It is named after Baron Guillaume Dupuytren, the surgeon who described an operation to correct the affliction.

Dupuytren's contracture is treated with procedures to help straighten the fingers, but this does not cure the underlying disease. Contractures often return or involve other fingers.

According to one study,[4][5] the ring finger is the finger most commonly affected, followed by the middle and little fingers; the thumb and index finger are only rarely affected. Dupuytren's contracture progresses slowly and is often accompanied by some aching and itching. In patients with this condition, the palmar fascia (palmar aponeurosis) thickens and shortens so that the tendons connected to the fingers cannot move freely. The palmar fascia becomes hyperplastic and contracts.

Incidence increases after age 40; at this age, men are affected more often than women. Beyond 80 the gender distribution is about even. In the United Kingdom, about 20% of people over 65 have some form of the disease.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Typically, Dupuytren's contracture first presents as a thickening or nodule in the palm, which initially can be with or without pain.[7] Later in the disease process, there is increasing painless loss of range of motion of the affected fingers. The earliest sign of a contracture is a triangular “puckering” of the skin of the palm as it passes over the flexor tendon just before the flexor crease of the finger, at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint. Generally, the cords or contractures are painless, but, rarely, tenosynovitis can occur and produce pain. The most common finger to be affected is the ring finger; the thumb and index finger are much less often affected.[4] The disease begins in the palm and moves towards the fingers, with the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints affected before the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints[8]

In Dupuytren's contracture, the palmar fascia within the hand becomes abnormally thick, which can cause the fingers to curl and can impair finger function. The main function of the palmar fascia is to increase grip strength; thus, over time, Dupuytren's contracture decreases patients' ability to hold objects. Patients may rarely report pain, aching and itching with the contractions. Normally, the palmar fascia consists of collagen type I, but in Dupuytren sufferers, the collagen changes to collagen type III, which is significantly thicker than collagen type I.

Types of Dupuytren's disease

According to the American Dupuytren's specialist Dr Charles Eaton, there may be three types of Dupuytren's disease:[9]

- Type 1: A very aggressive form of the disease found in only 3% of patients with Dupuytren's, which can affect men under 50 with a family history of Dupuytren's. It is often associated with other symptoms such as knuckle pads and Ledderhose disease. This type is sometimes known as Dupuytren's diathesis.[10]

- Type 2: The more normal type of Dupuytren's disease, usually found in the palm only, and which generally begins above the age of 50. According to Dr Eaton, this type may be made more severe by other factors such as diabetes or heavy manual labour.

- Type 3: A mild form of Dupuytren's which is common among diabetics or which may also be caused by certain medications such as the anti-convulsants taken by people with epilepsy. This type does not lead to full contracture of the fingers and is probably not inherited.

Related conditions

People with severe involvement often show lumps on the back of their finger joints (called “Garrod's pads”, “knuckle pads”, or “dorsal Dupuytren nodules”) and lumps in the arch of the feet (plantar fibromatosis or Ledderhose disease). In severe cases, the area where the palm meets the wrist may develop lumps. Severe Dupuytren disease may also be associated with frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis of shoulder), Peyronie's disease of the penis, increased risk of several types of cancer, and risk of early death, but more research is needed to clarify these relationships.

Risk factors

Dupuytren's contracture is a non-specific affliction, but primarily affects:

- People of Scandinavian or Northern European ancestry;[11] it has been called the "Viking disease",[6] though it is also widespread in some Mediterranean countries (e.g., Spain and Bosnia).[12] Dupuytren's is unusual among ethnic groups such as Chinese and Africans.[13]

- Men rather than women (men are more likely to develop the condition).[4][11]

- People over the age of 50; the likelihood of getting Dupuytren's disease increases with age.[4][13]

- Smokers, especially those who smoke 25 cigarettes or more a day.[13][14]

- Thinner people (i.e. those with a lower than average body mass index).[13]

- People with a higher than average fasting blood glucose level.[13]

- Manual workers.[13]

- People with previous hand injury.[4]

- People with a family history (60% to 70% of those afflicted have a genetic predisposition to Dupuytren's contracture).[4][15]

- People with Ledderhose disease.[4]

- Alcoholics.[6][14]

- People with epilepsy (possibly due to anti-convulsive medication).[16]

- People with diabetes mellitus.[6][16]

- People with HIV.[6]

In one study, those with stage 2 of the disease were found to have a slightly increased risk of mortality, especially from cancer.[17]

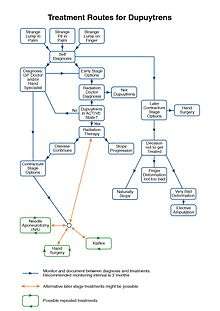

Treatment

Treatment is indicated when the so-called table top test is positive. With this test, the patient places his hand on a table. If the hand lies completely flat on the table, the test is considered negative. If the hand cannot be placed completely flat on the table, leaving a space between the table and a part of the hand as big as the diameter of a ballpoint pen, the test is considered positive and surgery or other treatment may be indicated. Additionally, finger joints may become fixed and rigid. Treatment using radiation therapy begins at an earlier stage. Radiation therapy is most effective when nodules and cords first appear, and before contracture begins.

Treatment involves one or more different types of treatment with some hands needing repeated treatment.

The main categories listed by the International Dupuytren Society in order of stage of disease are Radiation Therapy, Needle Aponeurotomy (NA), Collagenase Injection (Xiaflex) and Hand Surgery.

Radiation Therapy is effective at the early nodules and cords stage ("Stage N") and is also used at the N/I stage of 10 degrees or less of deformation.

Needle Aponeurotomy is most effective at "Stage I and Stage II" of 6-90 degrees of deformation. However, it is also used at other stages.

Collagenase Injection (Xiaflex) is most effective at "Stage I" and Stage II" of 6-90 degrees of deformation. However, it is also used at other stages.

Hand Surgery is effective at Stage I - Stage IV.[18]

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy has been reported to be effective for prevention of disease progression in early stages with only mild acute or late side effects. X-Ray and more recently E-beam radiation are used.

Finney first reported the effects of radiation treatment in the British Journal of Radiology in 1955.[19]

In Germany and parts of the U.S., radiotherapy is one of the main treatments. A global list of clinics offering radiation treatment for Dupuytren's and Ledderhose is maintained by the International Dupuytren Society.[20]

The results of fractionated radiation therapy were published in studies in 1996 and 2001.[21][22]

The effect of radiation therapy on a long-term outcome was evaluated by Betz et al.[23] They conducted a follow up evaluation 13 years later for patients receiving radiation therapy. Treatment toxicity and objective symptom reduction in terms of stage change and numbers of nodules and cords were assessed.[23] They concluded that radiotherapy is effective in prevention of disease progression and improves patients' symptoms in stage N, N/I. Given disease progression after radiotherapy, a "salvage" operation is still possible according to the authors.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[24] published guidelines and approval in November 2010. The guidance proposed a single phase of 15 grays (Gy) of treatment as standard for non severe cases.[25]

M.H. Seegenschmiedt, who began treating Dupuytren's with radiotherapy in 1987, presented his findings at the 2010 International Symposium on Dupuytren's Disease in Miami, USA. Seegenschmiedt stated that radiotherapy is an early stage treatment in which finger deformation should be 10 degrees or less. The most preferable state would be no deformation, with the hand diagnosed as an "active" state, in which nodules and cords are changing. During diagnosis the feet are checked for Ledderhose disease. The nodules and cords are irradiated for five days in a row with a dose of 3 Gy fractions per day, totaling 15 Gy for the week. The treatment is repeated after 12 weeks.[26]

The purpose of radiotherapy is to stop disease progression. It has a documented success rate of 85%.

Surgical

On June 12, 1831, Dupuytren performed a surgical procedure on a patient with contracture of the 4th and 5th digits who had been previously told by other surgeons that the only remedy was cutting the flexor tendons. He described this patient and operation in The Lancet in 1834 [27] after presenting it in 1833 and posthumously in 1836 in a French publication by Hôtel-Dieu de Paris.[28] The procedure he described was a minimally invasive needle procedure. Because of high recurrence rates, new surgical techniques were introduced, such as fasciectomy and then dermofasciectomy. Most of the diseased tissue is removed with these procedures. Recurrence rates are high. For some individuals, the partial insertion of "K wires" into either the DIP or PIP joint of the affected digit for a period of a least 21 days to fuse the joint is the only way to halt the disease's progress. After removal of the wires, the joint is fixed into flexion, which is considered preferable to fusion at extension.

In extreme cases, amputation of fingers may be needed for severe or recurrent cases, or after surgical complications.[29]

Limited fasciectomy

Limited/selective fasciectomy removes the pathological tissue, and is a common approach.[30][31]

During the procedure, the patient is under regional or general anesthesia. A surgical tourniquet prevents blood flow to the limb.[32] The skin is often opened with a zig-zag incision but straight incisions with or without Z-plasty are also described and may reduce damage to neurovascular bundles.[33] All diseased cords and fascia are excised.[30][31][32] The excision has to be very precise to spare the neurovascular bundles.[32] Because not all the diseased tissue is visible macroscopically, complete excision is uncertain.[31] A 20-year review of surgical complications associated with fasciectomy showed that major complications occurred in 15.7% of cases, including digital nerve injury (3.4%), digital artery injury (2%), infection (2.4%), hematoma (2.1%), and complex regional pain syndrome (5.5%), in addition to minor complications including painful flare reactions in 9.9% of cases and wound healing complications in 22.9% of cases.[34] After the tissue is removed, the surgeon closes the incision. In the case of a shortage of skin, the transverse part of the Zig-Zag incision is left open. Stitches are removed 10 days after surgery.[32]

After surgery, the hand is wrapped in a light compressive bandage for one week. Patients start bending and extending their fingers as soon as the anesthesia has resolved. Hand therapy is often recommended.[32] Approximately 6 weeks after surgery patients are able to completely use their hand.[35]

The average recurrence rate is 39% after a fasciectomy after a median interval of about 4 years.[36]

Wide-awake fasciectomy

Three centres worldwide have published the results of limited/selective fasciectomy under local anesthesia (LA) with epinephrine but no tourniquet. In 2005, Denkler described the technique. His 60 cases refuted several decades of surgical dogma that adrenaline cannot be used in digits and that Dupuytren's fasciectomy cannot be done under LA without a tourniquet.[37] In 2009 Lalonde described a multicentre comparative study of 111 cases having surgery under general or local anesthesia with equivalent results.[38]

In 2012, orthopedic surgeons Bismil et al. described the first high volume awake Dupuytren's service for 270 cases.[39] Their One Stop Wide Awake surgery (OSWA) required one thirty- to forty-five-minute management slot involving outpatient LA surgery.[39] Patients were taught range-of-motion exercises during the procedure and the surgeon used dynamic information to optimize the surgery. Accelerated rehabilitation can eliminate splinting. A modified boxing-glove bandage can prevent significant post-operative hematoma.[39]

Operating without a tourniquet is the only (comfortable) option for a wide awake patient, but is contrary to most hand surgeons' training. As of 2014, the technique was only routinely available from Robbins[33] in Australia, Denkler[37] in the US, Lalonde[38] in Canada or Bismil[39] in the UK. The largest series of wide awake fasciectomy utilizes the skin incisions described by Robbins,[33] with or without deferred Z-plasty, with greater patient safety and protection for the neurovascular bundle (straight incisions).[39]

Dermofasciectomy

Dermofasciectomy is a surgical procedure that is mainly used in recurrences and for patients with a high chance of recurrence.[31] Just like the limited fasciectomy, the dermofasciectomy excises diseased cords, fascia and the overlying skin.[40] The skin is then closed with a skin graft, usually full-thickness,[31][41] consisting of the epidermis and the entire dermis. In most cases the graft is taken from the elbow flexion crease or the proximal inner side of the arm.[40][41] This place is chosen, because the skin color best matches the palm's skin color. The skin on the proximal inner side of the arm is thin and has enough skin to supply a full-thickness graft. The donor site can be closed with a direct suture.[40]

The graft is sutured to the skin surrounding the wound. For one week the hand is protected with a dressing. The hand and arm are elevated with a sling. The dressing is then removed and careful mobilization can be started, gradually increasing in intensity.[40] After this procedure the recurrence of the disease can be low[31][40][41] but the re-operation and complication rate may be high.[42]

Free Vascular Flaps

In severe cases a free vascular flap may be preferred and is thought to reduce recurrence. A one-year follow-up of a single patient was described. This patient had not experienced recurrence.[43]

Segmental Fasciectomy with/without Cellulose

Segmental fasciectomy involves excising part(s) of the contracted cord so that it disappears or no longer contracts the finger. It is less invasive than the limited fasciectomy, because not all the diseased tissue is excised and the skin incisions are smaller.[44]

The patient is placed under regional anesthesia and a surgical tourniquet is used. The skin is opened with small curved incisions over the diseased tissue. If necessary, incisions are made in the fingers.[44] Pieces of cord and fascia of approximately one centimeter are excised. The cords are placed under maximum tension while they are cut. A scalpel is used to separate the tissues.[44] The surgeon keeps removing small parts until the finger can fully extend.[44][45] Patients start with active mobilization the day after surgery. They wear an extension splint for two to three weeks, except during physical therapy.[44]

The same procedure is used in the segmental fasciectomy with cellulose implant. After the excision and a careful haemostasis, the cellulose implant is placed in a single layer in between the remaining parts of the cord.[45]

After surgery patients wear a light pressure dressing for four days, followed by an extension splint. The splint is worn continuously during nighttime for eight weeks. During the first weeks after surgery the splint may be worn during daytime.[45]

Less invasive treatments

The patient burden after open surgery is high, therefore less invasive techniques may be preferred. New studies have been conducted for percutaneous release, extensive percutaneous aponeurotomy with lipografting and collagenase. These treatments show promise.[3][46][47][48]

Percutaneous Needle Fasciotomy

Needle aponeurotomy is a minimally-invasive technique where the cords are weakened through the insertion and manipulation of a small needle. The cord is sectioned at as many levels as possible in the palm and fingers, depending on the location and extent of the disease, using a 25 Gauge needle mounted on a 10 ml syringe.[3] Once weakened, the offending cords can be snapped by putting tension on the finger(s) and pulling the finger(s) straight. After the treatment a small dressing is applied for 24 hours. After these 24 hours patient are able to use their hands normally. No splints or physiotherapy are given.[3]

The advantage of needle aponeurotomy is the minimal intervention without incision (done in the office under local anesthesia) and the very rapid return to normal activities without need for rehabilitation, but the nodules may resume growing.[49] A study reported postoperative gain is greater at the MCP-joint level than at the level of the IP-joint and found a reoperation rate of 24%; complications are scarce.[50] Needle aponeurotomy may be performed on fingers that are severely bent (stage IV), and not just in early stages. A 2003 study showed 85% recurrence rate after 5 years.[51]

A comprehensive review of the results of needle aponeurotomy in 1,013 fingers was performed by Gary M. Pess, MD, Rebecca Pess, DPT and Rachel Pess, PsyD and published in the Journal of Hand Surgery April 2012. Minimal followup was 3 years. Metacarpophalangeal joint (MP) contractures were corrected an average of 99% and Proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) contractures an average of 89% immediately post procedure. At final follow-up, 72% of the correction was maintained for MP joints and 31% for PIP joints. The difference between the final corrections for MP versus PIP joints was statistically significant. When a comparison was performed between patients age 55 years and older versus under 55 years, there was a statistically significant difference at both MP and PIP joints, with greater correction maintained in the older group. Gender differences were not statistically significant. Needle aponeurotomy provided successful correction to 5° or less contracture immediately post procedure in 98% (791) of MP joints and 67% (350) of PIP joints. There was recurrence of 20° or less over the original post procedure corrected level in 80% (646) of MP joints and 35% (183) of PIP joints. Complications were rare except for skin tears, which occurred in 3.4% (34) of digits. This study showed that NA is a safe procedure that can be performed in an outpatient setting. The complication rate was low, but recurrences were frequent in younger patients and for PIP contractures.[52]

Extensive Percutaneous Aponeurotomy and Lipografting

A technique introduced in 2011 is extensive percutaneous aponeurotomy with lipografting.[46] This procedure also uses a needle to cut the cords. The difference with the percutaneous needle fasciotomy is, that the cord is cut at many places. The cord is also separated from the skin to make place for the lipograft that is taken from the abdomen or ipsilateral flank.[46] This technique shortens the recovery time. The fat graft results in supple skin.[46]

Before the aponeurotomy, a liposuction is done to the abdomen and ipsilateral flank to collect the lipograft.[46] The treatment can be performed under regional or general anesthesia. The digits are placed under maximal extension tension using a firm lead hand retractor. The surgeon makes multiple palmar puncture wounds with small nicks. The tension on the cords is crucial, because tight constricting bands are most susceptible to be cut and torn by the small nicks, whereas the relatively loose neurovascular structures are spared. After the cord is completely cut and separated from the skin the lipograft is injected under the skin. A total of about 5 to 10 ml is injected per ray.[46]

After the treatment the patient wears an extension splint for 5 to 7 days. Thereafter the patient returns to normal activities and is advised to use a night splint for up to 20 weeks.[46]

As of 2011 this treatment was performed only in Miami or Rotterdam. Prospective randomized comparative studies were in process.[46]

Collagenase

_for_Dupuytrens.jpg)

Clostridial collagenase is a pharmaceutical treatment option. The cords are weakened through the injection of small amounts of the enzyme collagenase, which breaks peptide bonds in collagen.[47][53][54][55][56]

The treatment with collagenase is different for the MCP joint and the PIP joint. In a MCP joint contracture the needle must be placed at the point of maximum bowstringing of the palpable cord.[47] The treatment consists of one injection with 0.58 mg 0.25 ml. collagenase clostridium histolyticum (CCH).[48]

The needle is placed vertically on the bowstring. The collagenase is distributed across three injection points.[47] For the PIP joint the needle must be placed not more than 4 mm distal to palmar digital crease at 2–3 mm depth.[47] The injection for PIP consists of one injection filled with 0.58 mg CCH 0.20 ml.[48] The needle must be placed horizontal to the cord and also uses a 3-point distribution.[47] After the injection the patient’s hand is wrapped in bulky gauze dressing and must be elevated for the rest of the day. After 24 hours the patient returns for passive digital extension to rupture the cord. Moderate pressure for 10–20 seconds ruptures the cord.[47]

After the treatment with collagenase the patient should use a night splint and perform digital flexion/extension exercises several times per day for 4 months.[47]

A study where patients were treated with these collagenase injections showed a recurrence rate of 67% in the MCP joint and 100% in the PIP joint. Although these recurrent rates are high, the recurrence was not as severe as the primary occurrence.[57] Another study showed recurrence rates of 35% in the MCP joint and 62% in the PIP joint after 4 years.[58] Collagenase injection is a nonsurgical option to treat Dupuytren’s disease and it provides the benefits of avoiding the potential surgical complications such as nerve injury, hematoma and skin necrosis. Primary surgery reports a 5% incidence of nerve injury and 12% in second surgery.

In February 2010 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved injectable collagenase extracted from Clostridium histolyticum for the treatment of Dupuytren's contracture.[59] The treatment is marketed under the tradename Xiaflex.[60] In February 2011, the European Commission's Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use approved the preparation for use in Europe, where it is marketed under the tradename Xiapex.

Alternative Therapies

Several alternate therapies such as vitamin E treatment, have been studied, although without control groups. Most doctors do not value those treatments.[61] None of these treatments stop or cure the condition permanently.

Laser treatment (using red and infrared at low power) was informally discussed in 2013 at an International Dupuytren Society forum,[62] as of which time little or no formal evaluation of the techniques had been completed.

Only anecdotal evidence supports other compounds as beneficial for Dupuytren's patients.[63]

- Quercetin

- Bromelain

- DMSO

- Methylsulfonylmethan

- Acetylcarnitine Hcl

- Para amino benzoic acid

- Nattokinase

- Vitamin E[64] This was investigated in the 1940s[65]

- Copper

- Vitamin C

Various forms of bodywork/massage also have only anecdotal support.

Prognosis

Dupuytren’s disease has a high recurrence rate, especially when a patient has so called Dupuytren’s diathesis. The term diathesis relates to certain features of Dupuytren's disease and indicates an aggressive course of disease.[10]

The presence of all new Dupuytren’s diathesis factors in a patient increases the risk of recurrent Dupuytren’s disease by 71% compared with a baseline risk of 23% in patients lacking the factors.[10] In another study the prognostic value of diathesis was evaluated. They concluded that presence of diathesis can predict recurrence and extension.[66] A scoring system was made to evaluate the risk of recurrence and extension evaluating the following values: bilateral hand involvement, little finger surgery, early onset of disease, plantar fibrosis, knuckle pads and radial side involvement.[66]

Minimally invasive therapies may precede higher recurrence rates. Recurrence lacks a consensus definition. Furthermore, different standards and measurements follow from the various definitions.

Postoperative care

Postoperative care involves hand therapy and splinting. Hand therapy is prescribed to optimize post-surgical function and to prevent joint stiffness.

Besides hand therapy, many surgeons advise the use of static or dynamic splints after surgery to maintain finger mobility. The splint is used to provide prolonged stretch to the healing tissues and prevent flexion contractures. Although splinting is a widely used post-operative intervention, evidence of its effectiveness is limited,[67] leading to variation in splinting approaches. Most surgeons use clinical experience to decide whether to splint.[68] Cited advantages include maintenance of finger extension and prevention of new flexion contractures. Cited disadvantages include joint stiffness, prolonged pain, discomfort,[68] subsequently reduced function and edema.

A third approach emphasizes early self-exercise and stretching.[39]

Society and culture

The International Dupuytren Society was founded in Germany in 2003.[69] It is a non-profit organization based in Germany where patients and medical experts cooperate,[70] without promoting specific treatment. Stated goals are informing the public about Dupuytren's Contracture and treatment options, and supporting research, patients and organizations. It publishes reliable medical results, and provides a discussion forum for practitioners and patients.

The society was founded by patient Wolfgang Wach,[69][71][72] In a presentation at the International Symposium on Dupuytrens Disease in Miami in 2010 he discussed receiving radiation and surgery.[69]

As of 2013 the chairs of the Society were Wach, Charles Eaton MD, and Heinrich Seegenschmiedt.[70]

Notable sufferers

- Bill Frindall, who had a finger amputated.[73]

- Bill Nighy

- Bob Dole

- David Gower[74]

- David McCallum

- Graham Gooch (wrongly reported as having had a finger amputated)[74]

- John Field (songwriter) from The Cockroaches and The Wiggles

- John Hawkins

- John Podesta[75]

- Jonathan Agnew[74][73]

- Margaret Thatcher[76]

- Michael Parks[77]

- Misha Dichter[78]

- Prince Joachim of Denmark[79]

- Robert Mahone

- Ronald Reagan[76]

- Samuel Beckett

References

- ↑ Freedberg, et al. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). Page 989. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ↑ Radiological Society of North America "Radiographics" article "Musculoskeletal Fibromatoses: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation" at http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/full/10.1148/rg.297095138

- 1 2 3 4 van Rijssen AL, Werker PM, Percutaneous needle fasciotomy in Dupuytren's disease. Hand Surg Br. 2006 Oct;31(5):498-501. Epub 2006 Jun 12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rosanne Lanting, Edwin R. van den Heuvel, Bram Westerink, Paul M.N. Werker. "Prevalence of Dupuytren Disease in The Netherlands", chapter 2, Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013; 132:394-403.

- ↑ But see also Bernd Loos, Valerij Puschkin and Raymund E Horch. "50 years experience with Dupuytren's contracture in the Erlangen University Hospital – A retrospective analysis of 2919 operated hands from 1956 to 2006". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dawn Hooper has it.M. G. Hart, G. Hooper. "Clinical associations of Dupuytren's disease". Postgraduate Medical Journal 2005; 81:425-428. doi=10.1136/pgmj.2004.027425

- ↑ "Dupuytren's contracture - Symptoms". National Health Service (England). Page last reviewed: 29/05/2015

- ↑ Nunn, Adam C.; Schreuder, Fred B. (2014). "Dupuytren's Contracture: Emerging insight into a Viking disease". Hand Surgery. 19 (03): 481–490. doi:10.1142/S0218810414300058. ISSN 0218-8104.

- ↑ Eaton, C. "Three types of Dupuytren Disease?" (Dupuytren's Foundation website)

- 1 2 3 Hindocha, Sandip; et al. (December 2006). "Dupuytren's Diathesis Revisited: Evaluation of Prognostic Indicators for Risk of Disease Recurrence". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 31 (10): 1626–1634. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.09.006. PMID 17145383.

- 1 2 "Your Orthopaedic Connection: Dupuytren's Contracture".

- ↑ "Age and geographic distribution of Dupuytren's disease (Dupuuytren's contracture)". Dupuytren-online.info. 2012-11-21. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kristján G. Gudmundsson, Reynir Arngrímsson, Nikulás Sigfússon, Árni Björnsson, Thorbjörn Jónsson. "Epidemiology of Dupuytren’s disease Clinical, serological, and social assessment. The Reykjavik Study." Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 53 (2000) 291–296.

- 1 2 "Smoking, alcohol and the risk of Dupuytren's contracture".

- ↑ "Dupuytren's Contracture".

- 1 2 "Etiology of Dupuytren's Disease" Living Textbook of Hand Surgery.

- ↑ Kristján G. Gudmundsson, Reynir Arngrímsson, Nikulás Sigfússon, Thorbjörn Jónsson."Increased total mortality and cancer mortality in men with Dupuytren's disease: A 15-year follow-up study" Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 55(1):5-10 February 2002

- ↑ "Progression of Dupuytren's disease". Dupuytren-online.info. 2012-08-18. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ↑ R. Finney (1955-11-01). "Dupuytren's Contracture". Bjr.birjournals.org. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ↑ "Clinics offering radiation therapy of Dupuytren's and Ledderhose disease". Dupuytren-online.info. 2013-02-20. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ↑ Seegenschmiedt MH, Olschewski T, Guntrum F (March 2001). "Radiotherapy optimization in early-stage Dupuytren's contracture: first results of a randomized clinical study". International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 49 (3): 785–98. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00745-8. PMID 11172962.

- ↑ Keilholz L, Seegenschmiedt MH, Sauer R (November 1996). "Radiotherapy for prevention of disease progression in early-stage Dupuytren's contracture: initial and long-term results". International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 36 (4): 891–7. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(96)00421-X. PMID 8960518.

- 1 2 Betz N, Ott OJ, Adamietz B, Radiotherapy in early-stage Dupuytren's contracture. Long-term results after 13 years. Strahlenther Onkol. 2010 Feb;186(2):82-90. Epub 2010 Jan 28.

- ↑ http://www.nice.org.uk/ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- ↑ "Radiation therapy for early Dupuytren's disease The procedure IPG368". Publications.nice.org.uk. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

- ↑ Charles Eaton; M. Heinrich Seegenschmiedt; Ardeshir Bayat; Giulio Gabbiani; Paul Werker; Wolfgang Wach (2012). Dupuytren’s Disease and Related Hyperproliferative Disorders Principles, Research, and Clinical Perspectives. pp. 355–364. ISBN 978-3642226960.

- ↑ Dupuytren, Guillaume (May 10, 1834). "Clinical Lectures on Surgery". The Lancet. 22 (558): 222–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)77708-8.

- ↑ Dupuytren, Guillaume (1836). "Rétraction Permanente des Doigts". Leçons orales de clinique chirurgicale, faites a l'Hotel-Dieu de Paris. 1: 1–12.

- ↑ "Surgical Complications Associated With Fasciectomy for Dupuytren's Disease: A 20-Year Review of the English Literature". Eplasty.com. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7538.397. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- 1 2 Hillel D. Skoff, M.D, The Surgical Treatment of Dupuytren’s Contracture: A Synthesis of Techniques. Hillel D. Skoff, M.D. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004 Feb;113(2):540-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Morsi Khashan, Peter J. Smitham, Dupuytren's Disease: Review of the Current Literature. Open Orthop J. 2011;5 Suppl 2:283-8. Epub 2011 Jul 28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 A. L. van Rijssen, F. S. J. Gerbrandy, A comparison of the direct outcomes of Percutaneous Needle Fasciectomy and Limited Fasciectomy for Dupuytren’s disease: A 6-week Follow-Up Study. J Hand Surg Am. 2006 May-Jun;31(5):717-25

- 1 2 3 Robbins, TH (September 1981). "Dupuytren's contracture: the deferred Z-plasty.". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 63 (5): 357–8. PMID 7271195.

- ↑ Denkler, Keith. Surgical complications associated with fasciectomy for Dupuytren's disease: a 20-year review of the English literature ePlasty 10 January 27, 2010. PMID 20204055

- ↑ Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2009;153;A129

- ↑ S.M. Crean, R.A. Gerber, M.P. Le Graverand, D.M. Boyd, J.C. Cappelleri. The efficacy and safety of fasciectomy and fasciotomy for Dupuytren's contracture in European patients: a structured review of published studies. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2011 Jun;36(5):396-407. Epub 2011 Mar 7.

- 1 2 Denkler K. Dupuytren's fasciectomies in 60 consecutive digits using lidocaine with epinephrine and no tourniquet. Plastic Reconstrive Surgery 2005. Volume 115:802–10

- 1 2 Nelson R, Higgins A, Conrad J, Bell M, Lalonde D. The Wide-Awake Approach to Dupuytren's Disease: Fasciectomy under Local Anesthetic with Epinephrine. Hand (N Y). 2009 Nov 10. [Epub ahead of print].

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bismil QMK, Bismil MSK, Bismil A, Neathey J, Gadd J, Roberts S, Brewster J. The development of one-stop wide-awake dupuytren's fasciectomy service: a retrospective review. J R Soc Med Sh Rep July 2012 vol. 3 no. 7 48doi: 10.1258/shorts.2012.012050

- 1 2 3 4 5 J.R. Armstrong, J.S. Hurren, A.M. Logan , Dermofasciectomy in the management of Dupuytren’s disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000 Jan;82(1):90-4.

- 1 2 3 A. S. Ullah, J. J. Dias, B. Bhowal, Does a ‘firebreak’ full-thickness skin graft prevent recurrence after surgery for Dupuytren’s contracture? A PROSPECTIVE, RANDOMISED TRIAL. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009 Mar;91(3):374-8.

- ↑ C. Bainbridge,L.B. Dahlin, P.P. Szczypa, J.C. Cappelleri, D. Guérin, R.A. Gerber. Current trends in the surgical management of Dupuytren’s disease in Europe: an analysis of patient charts. Eur Orthop Traumatol. 2012 March; 3(1): 31–41.

- ↑ O.A. Branford, M. Davis, F. Schreuder, The circumflex scapular artery perforator flap for palm reconstruction in a recurrent severe case of Dupuytren’s disease. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009 Dec;62(12):e589-91. Epub 2009 Feb 7

- 1 2 3 4 5 J.P. Moermans, Segmental aponeurectomy in Dupuytren’s disease. J Hand Surg Br. 1991 Aug;16(3):243-54.

- 1 2 3 I. Degreef, S. Tejpar, L. de Smet, Improved postoperative outcome of segmental fasciectomy in Dupuytren’s disease by insertion of an absorbable cellulose implant. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2011 Jun;45(3):157-64.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hovius SE, Kan HJ, Extensive percutaneous aponeurotomy and lipografting: a new treatment for Dupuytren disease. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Jul;128(1):221-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Thomas A, Bayat A., The emerging role of Clostridium histolyticum collagenase in the treatment of Dupuytren disease. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2010 Nov 4;6:557-72

- 1 2 3 Hurst LC, Badalamente MA, Hentz VR, Hotchkiss RN, Kaplan FT, Meals RA, Smith TM, Rodzvilla J; CORD I Study Group, Injectable collagenase clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren's contracture. N Engl J Med. 2009 Sep 3;361(10):968-79.

- ↑ Lellouche H (October 2008). "[Dupuytren's contracture: surgery is no longer necessary.]". Presse medicale (Paris, France : 1983). 37 (12): 1779–81. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2008.07.012. PMID 18922672.

- ↑ Foucher G, Medina J, Navarro R (2003). "Percutaneous needle aponeurotomy: complications and results.". J Hand Surg Br. 28 (5): 427–31. doi:10.1016/S0266-7681(03)00013-5. PMID 12954251.

- ↑ van Rijssen AL, Ter Linden H, Werker PM. 5-year results of randomized clinical trial on treatment in Dupuytren's disease: percutaneous needle fasciotomy versus limited fasciectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Oct 7.

- ↑ Pess GP, Pess RM, Pess RA (2012). "Results of needle aponeurotomy for Dupuytren contracture in over 1,000 fingers.". J Hand Surg Am. 37 (4): 651–6. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.01.029.

- ↑ Badalamente MA, Hurst LC (2007). "Efficacy and safety of injectable mixed collagenase subtypes in the treatment of Dupuytren's contracture". The Journal of hand surgery. 32 (6): 767–74. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.04.002. PMID 17606053.

- ↑ Badalamente MA, Hurst LC (July 2000). "Enzyme injection as nonsurgical treatment of Dupuytren's disease". The Journal of hand surgery. 25 (4): 629–36. doi:10.1053/jhsu.2000.6918. PMID 10913202.

- ↑ Badalamente MA, Hurst LC, Hentz VR (September 2002). "Collagen as a clinical target: nonoperative treatment of Dupuytren's disease". The Journal of hand surgery. 27 (5): 788–98. doi:10.1053/jhsu.2002.35299. PMID 12239666.

- ↑ Hurst LC, Badalamente MA, Hentz VR, Hotchkiss RN (September 2009). "Injectable Collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum for Dupuytren's Contracture". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (10): 968–971. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810866. PMID 19726771.

- ↑ Watt AJ, Curtin CM, Hentz VR, Collagenase injection as nonsurgical treatment of Dupuytren's disease: 8-year follow-up. J Hand Surg Am. 2010 Apr;35(4):534-9, 539.e1.

- ↑ http://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/clinicalguidance/drugmonographs/Collagenase_Clostridium_Histolyticum_XIAFLEX_Monograph_rev_July_2015.pdf, Collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum (XIAFLEX™) for Dupuytren’s Contracture National PBM Drug Monograph VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives, Table 3

- ↑ "FDA Approves Xiaflex for Debilitating Hand Condition". Fda.gov. 2010-02-02. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ↑ "XIAFLEX速 Dupuytren's Contracture Treatment for Adults with Palpable Cord | Xiaflex®". Xiaflex.com. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ↑ Proposed Natural Treatments for Dupuytren's Contracture, EBSCO Complementary and Alternative Medicine Review Board, 2 February 2011.Accessed 21 March 2011.

- ↑ Cold Laser Treatment at International Dupuytren Society online forum. Accessed: 28 August 2012.

- ↑ Therapies for Dupuytren's contracture and Ledderhose disease with possibly less benefit, International Dupuytren Society, 19 January 2011.Accessed: 21 March 2011.

- ↑ Flatt AE (October 2001). "The Vikings and Baron Dupuytren's disease". Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 14 (4): 378–84. PMC 1305903

. PMID 16369649.

. PMID 16369649. - ↑ Dupuytren's Contracture Treated with Vitamin E, H. J. Richards, British Medical Journal, 21 June 1952.Accessed 21 March 2011.

- 1 2 Abe Y, Rokkaku T, An objective method to evaluate the risk of recurrence and extension of Dupuytren's disease. J Hand Surg Br. 2004 Oct;29(5):427-30

- ↑ C. Jerosh - Herold, L. Shepstone, Splinting after contracture release for Dupuytren’s contracture (SCoRD): protocol of a pragmatic, multi-centre, randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008 Apr 30;9:62.

- 1 2 D. Larson, C. Jerosch-Herold, Clinical effectiveness of post-operative splinting after surgical release of Dupuytren’s contracture: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008 Jul 21;9:104

- 1 2 3 Presentation by W Wach at the International Symposium on Dupuytrens Disease in Miami in 2010. Abstract Recorded presentation

- 1 2 International Dupuytren Society: Goals and Management at official website. Accessed 9 November 2013

- ↑ Eaton, Charles et al. Dupuytren’s Disease and Related Hyperproliferative Disorders (Introductory pages) p.xviii

- ↑ German Biotechnology Days 2012 conference Web site, Wolfgang Wach

- 1 2 Jonathan Agnew, Aggers' Ashes (London, 2011), page 103

- 1 2 3 Elkins, Lucy (6 December 2010). "Why the voice of cricket Jonathan 'Aggers' Agnew wants to chop off his finger". Daily Mail. London.

- ↑ https://wikileaks.org/podesta-emails/emailid/47943. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Drug Approved to Treat Hand-Crippling Syndrome, Delthia Ricks, Chicago Tribune, March 17, 2010.

- ↑ "Biography". IMDB.

- ↑ Pollack, Andrew (March 15, 2010). "Triumph for Drug to Straighten Clenched Fingers". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Joachim opereret for krumme fingre". HER&NU. March 17, 2013.