Zuccotti Park

| Zuccotti Park | |

|---|---|

|

(2015) | |

| |

| Type | Plaza |

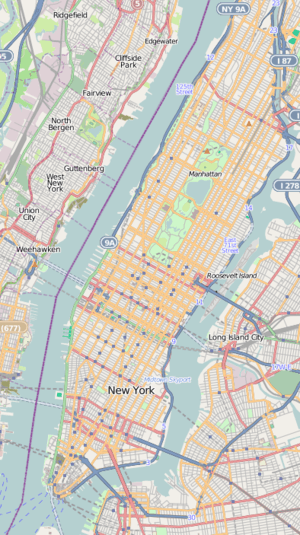

| Location | New York City, United States |

| Coordinates | 40°42′34″N 74°00′41″W / 40.709385°N 74.011323°WCoordinates: 40°42′34″N 74°00′41″W / 40.709385°N 74.011323°W |

| Area | 33,000 square feet (3,100 m2) |

| Created | 1968 |

| Etymology | Named after John E. Zuccotti, Brookfield Office Properties CEO |

| Operated by | Brookfield Office Properties |

| Status | Open all year |

Zuccotti Park, formerly called Liberty Plaza Park, is a 33,000-square-foot (3,100 m2) publicly accessible park in Lower Manhattan, New York City, located in a privately owned public space (POPS) controlled by Brookfield Properties.[1][2][3] The park was created in 1968 by Pittsburgh-based United States Steel, after the property owners negotiated its creation with city officials. It was named Liberty Plaza Park because it was situated beside One Liberty Plaza, which was located between Broadway, Trinity Place, Liberty Street, and Cedar Street. The park's northwest corner is across the street from Four World Trade Center. It has been popular with local tourists and financial workers.

The park was heavily damaged in the September 11 attacks and subsequent recovery efforts of 2001. The plaza was later used as the site of several events commemorating the anniversary of the attacks. After renovations in 2006, the park was renamed by its current owners, Brookfield Office Properties, after company chairman John Zuccotti. In 2011, the plaza became the site of the Occupy Wall Street protest camp, during which activists occupied the plaza and used it as a staging ground for their protests throughout Financial District, Manhattan.

History

Development

The site was the location of the first coffeehouse in colonial New York City, The King's Arms which opened under the ownership of Lieutenant John Hutchins in 1696. It stood on the west side of Broadway between Crown (now Liberty) Street and Little Queen (now Cedar) Street.[4] On November 5, 1773, summoned by the Sons of Liberty, a huge crowd assembled outside the coffee house to denounce the Tea Act, and agents of the East India Trading company who were handling cargoes of dutied tea. It was perhaps the first public demonstration in opposition to the Tea Act in the American colonies.[5]

The park, formerly called Liberty Plaza Park, was created in 1968 by Pittsburgh-based U.S. Steel in return for a height bonus for an adjacent building at the time of its construction. The U.S. Steel Building, which replaced the demolished Singer Building, is now known as One Liberty Plaza.[6] The park was one of the few open spaces with tables and seats in the Financial District. Located one block from the World Trade Center, it was covered with debris, and subsequently used as a staging area for the recovery efforts after the destruction of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001.[7] As part of the Lower Manhattan rebuilding efforts, the park was regraded, trees were planted, and the tables and seating restored.[6]

On June 1, 2006, the park reopened after an $8 million renovation designed by Cooper, Robertson & Partners. It was renamed Zuccotti Park in honor of John E. Zuccotti, former City Planning Commission chairman and first deputy mayor under Abe Beame and now the chairman of Brookfield Properties,[8] which used private money to renovate the park. Currently, the park has a wide variety of trees, granite sidewalks, tables and seats, as well as lights built into the ground, which illuminate the area. With its proximity to Ground Zero, Zuccotti Park is a popular tourist destination. The World Trade Center cross, which was previously housed at St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church, was featured in a ceremony held in Zuccotti Park before it was moved to the 9/11 Memorial.[9] The park won the 2008 American Institute of Architects Honor Award for Regional and Urban Design and was featured in Architectural Record and International New Architecture magazines.[10]

.jpg)

Sculptures

The park is home to two sculptures: Joie de Vivre by Mark di Suvero and Double Check, a bronze businessman sitting on a bench, by John Seward Johnson II.[7][11][12][13]Joie de Vivre, a 70-foot-tall sculpture consisting of bright-red beams, was installed in Zuccotti Park in 2006, having been moved from its previous installation in the Storm King Art Center. Benjamin Genocchio, an Australian art critic, commented that the sculpture suited the location, "nicely echoing the skyscrapers around it."[14]

Encampment of Protesters of Occupy Wall Street

During the Occupy Wall Street Movement, many protesters inhabited Zuccotti Park and spent their days including nights there. Although park rules were that overnight stay was not permitted, protesters remained in the park. There had been previous attempts to clear out the park, but the NYPD had been unsuccessful. However, on November 15, 2011, all of the protesters in the park were driven out and evicted[1]. The police officers lit up flood lights and began to clear out the park[2]. Tents, tarps, and other forms of shelters were immediately removed in order to clear out the park. In efforts to remain in the park, protesters began to protest against the police. The commotion only led for the pepper-spraying of the protesters as well as getting protesters detained[3]. After the park was reopened to the public, it was let known that protesters were still permitted to exercise their civil rights, but that their rights did not include sleeping and camping out at the park[4]. The protesters remained at the site which led to the continuous conflict between the participants in the Wall Street Movement and the police department.

After the complete eviction of the protesters, the protesters rallied and attempted to take over other locations. Although they did not possess all of the permits to protest in certain areas, protesters were joined by other fellow New Yorkers as well as other citizens from other cities in effort to raise awareness of the wrongdoings of the banks and the economic system.

Protesters still protest against Wall Street despite not having Zuccotti Park in other locations like the Brooklyn Bridge, as well as other universities and private buildings.

also

New York City portal

New York City portal- List of privately owned public spaces in New York City

- Occupation of Alcatraz

- People's Park (Berkeley)

References

Notes

- ↑ Lisa W. Foderaro (November 13, 2011). "Privately Owned Park, Open to the Public, May Make Its Own Rules". The New York Times. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Privately Owned Public Space". New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ↑ nyc.gov Department of City Planning. "Privately Owned Public Space". Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ↑ Burrows and Wallace (1999), p.108

- ↑ Burrows and Wallace (1999), p.214

- 1 2 "Liberty Plaza Construction to Begin this Spring". Battery Park City Broadsheet. January 21, 2004. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- 1 2 "Brookfield Properties Re-Opens Lower Manhattan Park Following $8 Million Renovation" (Press release). June 1, 2006. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ↑ Colford, Paul D. (June 2, 2006). "Park Honor for Ex-City Official". Daily News. New York. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ↑ "WTC Cross' is Installed in 9/11 Memorial Museum". July 23, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2011.

- ↑ "Zuccotti Park". Cooper, Robertson & Partners. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Zuccotti Park Opens at Broadway and Liberty Street". Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. June 1, 2006. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ↑ "Liberty Plaza Park Turns Over a New Leaf". Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. July 25, 2005. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ↑ Dunlap, David W. (June 1, 2006). "Back at His Bench Downtown, Having Survived 9/11". The New York Times. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ↑ Genocchio, Benjamin (June 23, 2006). "Works of a Major Player In Macho Sculpture". The New York Times. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

Bibliography

- Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike (1999), Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-195-11634-8

External links

-

Media related to Zuccotti Park at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Zuccotti Park at Wikimedia Commons

.png)