Iron Knob

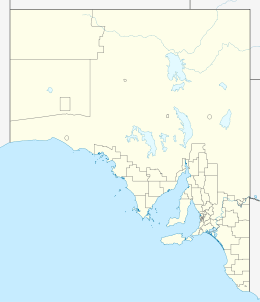

| Iron Knob South Australia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

Iron Knob | |||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 32°43′0″S 137°09′0″E / 32.71667°S 137.15000°ECoordinates: 32°43′0″S 137°09′0″E / 32.71667°S 137.15000°E | ||||||||||||

| Population | 199 (2006 census)[1] | ||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 5611 | ||||||||||||

| Location |

| ||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | Outback Communities Authority | ||||||||||||

| Region | Eyre and Western | ||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Giles[2] | ||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Grey[3] | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Footnotes | Adjoining localities[4] | ||||||||||||

Iron Knob is a town in the Australian state of South Australia on the Eyre Peninsula immediately south of the Eyre Highway. At the 2006 census, Iron Knob and the surrounding area had a population of 199.[1] The town obtained its name from its proximity to large deposits of iron ore, most notably Iron Monarch which outcropped prominently from the relatively flat, surrounding landscape.

Iron ore mining

The name Iron Knob first appeared on pastoral lease maps of 1854, and the first mineral claim in the area was pegged by the Broken Hill Proprietary Company in 1897. Mining commenced in 1900 and iron ore was transported by bullock wagon to Port Augusta then by rail to Port Pirie where it was used as a flux in the lead smelter there.[5][6] In 1901 a tramway from Iron Knob to Hummock Hill (later renamed Whyalla) was completed, followed by wharves in 1903. These allowed the direct loading of ships which could transport the ore across Spencer Gulf to Port Pirie.[5]

Iron Knob's iron ore proved to be of such high quality (upwards of 60% purity) that it led to the development of the Australian steel industry. It supplied iron to Newcastle for and steel works established at Newcastle and Port Kembla in the 1910s and 1920s and Whyalla in the 1930s. The iron ore was transported by railway to Whyalla[7] where it was either smelted or dispatched by sea.

21% of the steel required for the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge[8] was quarried at Iron Knob and smelted at Port Kembla, New South Wales. The remaining 79% was imported from England.[8]

In the 1920s, iron ore from Iron Knob was exported to the Netherlands and the United States of America.[9] In the 1930s, customers included Germany and Great Britain.[10][11]

Prior to World War II, iron ore from Iron Knob was also exported to Japan.[12][13][14][15] In the financial year 1935-36, 291,961 tonnes of ore from Iron Knob was shipped there via the seaport of Whyalla.[16] This became a controversial matter in the late 1930s due in part to Australia's known reserves at the time being limited to Iron Knob and Yampi Sound in Western Australia. Japan was also considered an 'aggressor' nation following acts of war against China in 1937.[17][18] Waterfront workers and seamen protested against the export of iron ore to Japan, leading to strikes and arrests.

In 1937, output from the Middleback Range, mostly from Iron Monarch was estimated at 2 mtpa.[19] In 1939, it was referred to in England as the highest grade deposit of iron ore known in the world.[20] In 1943, the iron Knob deposit was still delivering an average ore grade of 64 percent metallic content.[21] In 1949, 99% of Australian demand for iron ore was met by supply from Iron Knob and associated mines in South Australia,[22] having risen from 95% in 1943.[21]

Additional deposits of iron ore were developed by the Broken Hill Proprietary Company further south along the Middleback Range. including Iron Baron, Iron Prince and Iron Queen (discovered in 1920) and Iron Knight, Iron Duchess and Iron Duke (discovered in 1934).[5]

Mine closure and re-opening

Quarrying for iron at Iron Knob and Iron Monarch ended in 1998.[23] When the quarrying stopped, the town population reduced to 200[24] and Iron Knob was under threat of becoming a ghost town. However, due to rising prices of housing elsewhere, the town has attracted new residents seeking low cost residences. A home could be purchased for approximately A$35,000–70,000 and vacant land could be purchased for less than A$15,000.

In 2010, Onesteel (now Arrium Ltd) announced that it would return to Iron Knob to reopen the Iron Monarch mine.[23] The Iron Monarch mine was prepared for reopening by Arrium Ltd in 2013.[25] As of 2015, both Iron Monarch and Iron Duke continue to produce iron ore for export and for smelting at the Whyalla steelworks.

Transport

In the early days of mining at Iron Knob, ironstone was carted by oxen to Hummock Hill (renamed Whyalla in 1914). Approximately 300 tonnes was delivered in a good week. Construction of a private railway greatly increased transportation rates and by 1939, 9,000 tonnes of ore was delivered daily to Whyalla by rail. Later trains carried 2000 ton loads.

Ships operated by the then BHP company were similarly named Iron This and Iron That, some of which were built by the company at the Whyalla steelworks.

See also

References

- 1 2 Australian Bureau of Statistics (25 October 2007). "Iron Knob (State Suburb)". 2006 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ↑ "District of Giles Background Profile". ELECTORAL COMMISSION SA. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ "Federal electoral division of Grey, boundary gazetted 16 December 2011" (PDF). Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ "Search result for "Iron Knob (LOCB)" (Record no SA0022902) with the following layers selected - "Suburbs and Localities" and " Place names (gazetteer)"". Property Location Browser. Government of South Australia. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 Drexel, John F. (1982). Mining in South Australia - A Pictorial History. Government of South Australia - Department of Mines & Energy. p. 221. ISBN 0 7243 6094 8. ISSN 0726-1527.

- ↑ "WHYALLA AND IRON KNOB THEIR VALUE TO NATION IRON ORE PRODUCTION". Daily Advertiser. 10 January 1940. p. 5. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- ↑ Iron Knob Tramway Singleton, C.C. Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin, February, 1942 pp15-17

- 1 2 "Bridge History - Pylon Lookout". Pylon Lookout. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- ↑ "IRON ORE FOR EUROPE Increasing Trade Reported". News. 11 June 1929. p. 13. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ "ACTIVITIES AT IRON KNOB Ore For Newcastle Steel Works". Recorder. 24 July 1935. p. 4. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ "IRON ORE LOADINGS. At Whyalla.". Daily Commercial News and Shipping List. 22 May 1936. p. 4. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ "IRON ORE. Vessels to Load.". Daily Commercial News and Shipping List. 20 February 1935. p. 4. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- ↑ "FROM WHYALLA. Iron Ore For Japan.". Daily Commercial News and Shipping List. 24 April 1936. p. 4. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- ↑ "IRON ORE FOR JAPAN TROUBLE ON BRITISH STEAMER PORT KEMBLA, Tuesday.". Daily Advertiser. 20 April 1938. p. 1. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- ↑ "NOTES.". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate. 10 October 1929. p. 3. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ "S.A. SHIPS MUCH IRON ORE TO JAPAN Worth £158,000 in 1935-6". News. 8 September 1936. p. 15. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ "THE IRON ORE MYSTERY". National Advocate. 19 December 1938. p. 2. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ "CURRENT COMMENT. The War in China.". Kapunda Herald. 15 October 1937. p. 1. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ "S.A's. WEALTH OF IRON Huge Production At Iron Knob". Barrier Miner. 25 March 1937. p. 3. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ "The Recorder WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 16, 1939 SOUTH AUSTRALIAN MANUFACTURERS HOPE FOR STEELWORKS AT WHYALLA Pirie's Claims As Site For Factories". Recorder. 16 August 1939. p. 2. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- 1 2 "South Australia's Most Important Production Centre ... Whyalla, The Iron Town, At War". The Advertiser. 31 July 1943. p. 3. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ "South Australian Iron Ore Valuable". Kalgoorlie Miner. 24 November 1949. p. 1. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- 1 2 "OneSteel plans to reopen old mines". ABC News. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ "South Australian ghost town gets a boost". ABC Rural. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- ↑ "Iron Knob Preparations in Full Swing 17 Sep 2013 - Arrium". www.arrium.com. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Iron Knob. |