Scleritis

| Scleritis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Inflammation of entire thickness of the sclera | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | ophthalmology |

| ICD-10 | H15.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 379.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 11898 |

| MedlinePlus | 001003 scleritis. 001019 episcleritis |

| eMedicine | emerg/521 oph/642 |

| MeSH | D015423 |

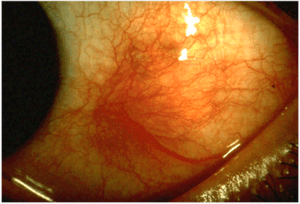

Scleritis is a serious inflammatory disease that affects the white outer coating of the eye, known as the sclera. The disease is often contracted through association with other diseases of the body, such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis or rheumatoid arthritis. There are three types of scleritis: diffuse scleritis (the most common), nodular scleritis, and necrotizing scleritis (the most severe). Scleritis may be the first symptom of onset of connective tissue disease.[1]

Episcleritis is inflammation of the episclera, a less serious condition that seldom develops into scleritis.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of scleritis include:[3]

- Redness of the sclera and conjunctiva, sometimes changing to a purple hue

- Severe ocular pain, which may radiate to the temple or jaw. The pain is often described as deep or boring.

- Photophobia and tearing

- Decrease in visual acuity, possibly leading to blindness

The pain of episcleritis is less severe than in scleritis.[4] In hyperemia, there is a visible increase in the blood flow to the sclera (hyperaemia), which accounts for the redness of the eye. Unlike in conjunctivitis, this redness will not move with gentle pressure to the conjunctiva.

Classification

Scleritis can be classified as anterior scleritis and posterior scleritis. Anterior scleritis is the most common variety, accounting for about 98% of the cases. It is of two types : Non-necrotising and necrotising. Non-necrotising scleritis is the most common, and is further classified into diffuse and nodular type based on morphology. Necrotising scleritis accounts for 13% of the cases. It can occur with or without inflammation.

Pathophysiology

Most of the time, scleritis is not caused by an infectious agent.[5]Histopathological changes are that of a chronic granulomatous disorder, characterized by fibrinoid necrosis, infiltration by polymorphonuclear cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages. The granuloma is surrounded by multinucleated epitheloid giant cells and new vessels, some of which may show evidence of vasculitis.

Diagnosis

Scleritis is best detected by examining the sclera in daylight; retracting the lids helps determine the extent of involvement. Other aspects of the eye exam (i.e. visual acuity testing, slit lamp examination, etc.) may be normal. Scleritis may be differentiated from episcleritis by using phenylephrine or neosynephrine eye drops, which causes blanching of the blood vessels in episcleritis, but not in scleritis.[4]

Ancillary tests CT scans, MRIs, and ultrasonographies can be helpful, but do not replace the physical examination.

Treatment

In very severe cases of necrotizing scleritis, eye surgery must be performed to repair damaged corneal tissue in the eye and preserve the patient's vision. For less severe cases, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen, are prescribed for pain relief. Scleritis itself is treated with an oral medication containing corticosteroids and an eye solution. In some cases, antibiotics are prescribed. Simply using eye drops will not treat scleritis. In more aggressive cases of scleritis, chemotherapy (such as systemic immunosuppressive therapy with such drugs as cyclophosphamide or azathioprine) may be used to treat the disease. If not treated, scleritis can cause blindness.

Complications

Secondary keratitis or uveitis may occur with scleritis.[4] The most severe complications are associated with necrotizing scleritis.

Epidemiology

Scleritis is not a common disease, although the exact prevalence and incidence are unknown. It is somewhat more common in women, and is most common in the fourth to sixth decades of life. [6]

References

- ↑ "Scleritis". WebMD, LLC. Medscape. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ↑ "Episcleritis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". Bethesda, MD: United States National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ↑ Vorvick, Linda J. (July 28, 2010). "Scleritis". PubMed Health. United States National Library of Medicine. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Goldman, Lee (2011). Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. p. 2440. ISBN 1437727883.

- ↑ Yanoff, Myron; Jay S. Duker (2008). Ophthalmology (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Mosby. pp. 255–261. ISBN 978-0323057516.

- ↑ Maite Sainz de la Maza (Feb 15, 2012). The sclera (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 102. ISBN 978-1441965011.

- Rosenbaum JT. The Eye and rheumatic diseases. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Harris ED Jr, et al., eds. Kelley's Textbook of Rheumatology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2008:chap 46.

- Watson P. Diseases of the sclera and episclera. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, eds. Duane’s Ophthalmology. 15th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:chap 23.