Kokomo, Indiana

| Kokomo, Indiana | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

|

The Art Deco Howard County courthouse. Part of the Courthouse Square Historical District, which is one of the places in Kokomo on the National Register of Historic Places. | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): City of Firsts | ||

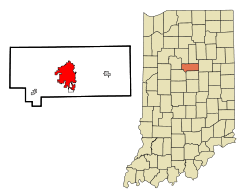

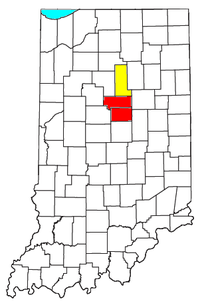

Location of Kokomo in the state of Indiana | ||

| Coordinates: 40°28′56″N 86°7′54″W / 40.48222°N 86.13167°WCoordinates: 40°28′56″N 86°7′54″W / 40.48222°N 86.13167°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | Indiana | |

| County | Howard | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Greg Goodnight (D) | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Total | 18.56 sq mi (48.07 km2) | |

| • Land | 18.50 sq mi (47.91 km2) | |

| • Water | 0.06 sq mi (0.16 km2) | |

| Elevation | 811 ft (247 m) | |

| Population (2010)[2] | ||

| • Total | 45,468 | |

| • Estimate (2014[3]) | 57,085 | |

| • Density | 2,457.7/sq mi (948.9/km2) | |

| Time zone | EST (UTC-5) | |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) | |

| ZIP codes | 46901-46904 | |

| Area code(s) | 765 | |

| FIPS code | 18-40392 | |

| GNIS feature ID | 0437425[4] | |

| Website | www.CityOfKokomo.org | |

Kokomo /ˈkoʊkəmoʊ/ is a city in and the county seat of Howard County, Indiana, United States.[5] Kokomo is Indiana's 13th-largest city. It is the principal city of the Kokomo, Indiana Metropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Howard and Tipton counties. Kokomo's population was 46,113 at the 2000 census, and 45,468 at the 2010 census.[6] On January 1, 2012, Kokomo successfully annexed more than 7 square miles (18 km2) on the south and west sides of the city, including Alto and Indian Heights, increasing the city's population to nearly 57,000 people.[7]

Named for the Miami Ma-Ko-Ko-Mo who was called "Chief Kokomo",[8] Kokomo first benefited from the legal business associated with being the county seat. Before the Civil War, it was connected with Indianapolis and then the Eastern cities by railroad, which resulted in sustained growth. Substantial growth came after the discovery of large natural gas reserves, which produced a boom in the mid-1880s. Among the businesses which the boom attracted was the fledgling automobile industry. A significant number of technical and engineering innovations were developed in Kokomo, particularly in automobile production, and, as a result, Kokomo became known as the "City of Firsts." A substantial portion of Kokomo's employment still depends on the automobile industry.

History

The Elwood Haynes House, Kokomo City Building, Kokomo Country Club Golf Course, Kokomo Courthouse Square Historic District, Kokomo High School and Memorial Gymnasium, Lake Erie and Western Depot Historic District, Learner Building, Old Silk Stocking Historic District, and Seiberling Mansion are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[9]

Early history and incorporation

The settler tradition says Kokomo was named for Kokomoko or[Ma-Ko-Ko-Mo] (meaning "black walnut"), shortened to Kokomo, said to have been one of the four sons of Chief Richardville last of the chiefs of the Miami people. Folklore holds that he was 7 feet (2.1 m) tall and falsely gives him the title of "chief."[10] David Foster, known as the "Father of Kokomo," claimed that he named the town Kokomo after the "ornriest Indian on earth" because Kokomo was "the ornriest town on earth."[11] Kokomo is thought to have been born in 1775 and died in 1838.[12] The only documentary proof of his existence is a trading post record of a purchase of a barrel of flour for $12 for his "squaw."[10] His remains (with those of others) were reportedly discovered during the construction of a saw mill in 1848 and re-interred in the "north-east corner" of the Pioneer Cemetery.[11] The tradition of the Peru Miami is that the town was named after a Thorntown Miami named Ko-kah-mah, whose name is rendered Co-come-wah in the Treaty at the Forks of the Wabash in 1834. That name was translated as "the diver" (an animal that could swim under water).[13]

As a result of various removals, by 1840 the Miami population in Howard County (until 1846 known as Richardville County) was reduced to about 200. The principal settlement was the Village of Kokomo, on the south side of Wildcat Creek. Indian paths connected Kokomo with Frankfort and Thorntown (along the Wildcat) and led to Peru by way of Cassville, and to Meshingomesia by way of Greentown.[12] At the time David Foster had a trading post in Howard County, near the intersection of the reservation boundary line and Wildcat pike, where he engaged in both legitimate trade and illegal sale of alcohol to the Miamis on government property.[14]

Shortly after Richardville County was organized in 1844 the commissioners appointed to establish the county seat approached Foster for a donation from his substantial holdings. (In 1846 tax records show that he owned 552 acres (223 ha) of farmland and as well as 67 divided lots in the business district.[15]) At the time of the request the only improvements in what is now Kokomo were Foster's log house and log barn and several Miami huts. The commissioners sought a donation of the more fertile lands south of Wildcat Creek, but Foster refused, donating instead 40 acres (16 ha) north of the creek—land which was thickly forested and "swampy."[16] The terms of the donation required that Foster build a courthouse on the land, but he was later excused and Rufus L. Blowers was promised $28 to build it. He was penalized $2 for construction delays.[17] The log courthouse was completed in 1845.[18]

In June 1855 Henry A. Brouse petitioned the board of Howard county commissioners to incorporate the town of Kokomo. The original election was not held (for unspecified reasons), but another took place on October 1, 1855. After a vote of 62–3 in favor of incorporation, the board so ordered it.[19]

On March 31, 1865, an election was held for Kokomo to assume a city government. The resolution was passed, and Nelson Purdum was elected the first mayor.[20]

Early growth

In anticipation of business that the court would bring, Kokomo began a fairly quick growth from the time that lots were first sold on October 18, 1844.[18] David Foster was granted the first license to sell merchandise in Kokomo at the December 1844 commissioners meeting. Two more merchants were licensed in March 1845.[21] John Bohan, who would become a major shop owner, merchant, justice of the peace and investor, moved to Kokomo in December 1844, and erected the first two story frame house, not only in Kokomo, but in all the county.[21][22]

After the enactment of the 1846 pre-emption law,[23] settlers rapidly attempted to secure homesteads in the surrounding lands.[24]

In 1848 Stonebreaker's Mill, 10 miles (16 km) west of Kokomo, began operations.[14][18] By 1850 Kokomo had a newspaper, when James Beard purchased the printing equipment of the New London Pioneer and set up the Howard Tribune.[25] By 1851 county business was so brisk that the county ordered the construction of two more court buildings, both one story brick affairs, 18 by 36 feet (5.5 by 11.0 m). The county auditor and treasurer occupied one building, and the clerk and recorder occupied the other.[26]

On April 1, 1854, Kokomo's first bank, the Indian Reserve Bank, was organized with David Foster, John Bohan and Harless Ashly the principal shareholders. (It only lasted a few years until a robbery impaired its capital. The loss substantially injured Foster's fortune.)[27]

Railroads

The year 1854 saw the first railroad stop at Kokomo.[18] The New London Pioneer had long advocated for a rail line to connect Kokomo with Indianapolis. Colonel C.D. Murray was the agent at Kokomo for stock subscriptions in support of the railroad. In 1852 the construction of the Peru and Indianapolis Railroad commenced. In Kokomo Samuel C. Mills and Dr. Corydon Richmond, commercial competitors of David Foster, donated several lots to the railroad in order to secure the location of the rail depot near their commercial property. The route was laid along Buckeye Street at the insistence of the merchants who hoped to reduced drayage expenses. Samuel Mills built a large frame structure at the Howard flouring mills, which served as a warehouse for the company's freight and a passenger depot. For some time after 1854 Kokomo was the terminus of the line, but eventually the line was extended to Peru and then to Michigan City.[28]

A short time after the construction of the Peru and Indianapolis Railroad began, the Pennsylvania Railroad announced that one of its lines would pass through Kokomo. By 1853 a line was commenced between Kokomo and Logansport (which was intended to become the hub of a network of lines for the company). Railroad service was inaugurated on that line on July 4, 1855.[29]

The most important rail line for Kokomo became the standard-gauge Clover Leaf line. This railroad would eventually link Kokomo with both the West Coast and the Eastern Seaboard. It began as a short line linking Frankfort and Kokomo, the Frankfort and Kokomo Railroad. Henry Y. Morrison of Frankfort was the principal promoter, and A.Y. Comstock acted for him in Kokomo. A failure of the proposed subsidy caused the promoters to turn all assets over to the contractors, who promised to complete the line. Construction began in 1873 and was completed the following year. Limited freight between the two cities made the line unprofitable. After a series of acquisitions by other railroads, the line became part of the Toledo, St. Louis and Kansas City Railroad. A line connecting it to the east reached Kokomo on January 1, 1881.[30]

Mayor Cole

In 1881, one of the most remarkable and controversial events in Kokomo's history took place. Mayor Henry C. Cole was shot to death by a sheriff's posse. Dr. Cole had a curious history and had stirred up a great deal of passion in the previous fifteen years. He was reputed to have been a gifted surgeon, who served in the Union Army during the Civil War and when afterwards he settled in Kokomo, he became a prominent physician. In Kokomo he married a woman, Natalie Cole, of whom he became intensely jealous.[31] He became suspicious of one Allen, whom he warned away from Kokomo. When he discovered Allen leaving the post office one day in October 1866, he shot him dead.[32] The fact that the killing both took place in broad daylight and showed cold-blooded rage (Cole continued shooting after Allen was down) caused the crime to receive national attention.[33] Cole's case was venued to Tipton County, where he retained Daniel W. Voorhees of Terre Haute to represent him.[31] Voorhees obtained a not guilty verdict on a plea of emotional insanity.[34] Cole divorced his wife thereafter.

Cole's reputation for violent instability, and the cowardice in the way he killed Allen, created many enemies for him, but his generosity toward poor patients and a promise to "clean up" the town won him enough support to win a bitter election for Mayor in 1881.[31][34] Shortly thereafter, on September 19, 1881, he was shot dead by a sheriff's posse at Old Spring Mills at West Jefferson Street.[31] According to the coroner's inquest, he died from shotgun wounds inflicted by Deputy George Bennett (father of New York stage idol Richard Bennett).[35] The sheriff claimed that an informant had advised him that Cole was planning to rob a flour mill, possibly to incriminate his enemies. The posse was forced to fire on Cole in self-defense (the sheriff claimed he had two revolvers) and to prevent his escape, although his injuries seemed inconsistent with that version.[35][36] Cole's supporter's argued that no revolvers or burglary tools were produced and that the motive was implausible.[35] Nevertheless, no action was taken against Bennett or others of the posse.

Natural gas boom

Natural gas had been developed in Pennsylvania and Canada for some time, and had most recently been developed around Findlay, Ohio. In March 1886, a group of citizens, led principally by A.Y. Comstock (who had promoted the Frankfort and Kokomo Railroad) and D.C. Spraker (later President of Kokomo Rubber Company), circulated a memorandum seeking subscribers (at $100 each) for the purpose of boring for gas at a distance of at least 2,000 feet (610 m) below ground. It took until September to obtain the necessary 22 subscribers. The first rig was built south of Wildcat Creek. and on October 6, 1886, natural gas erupted forth and the well was capped.[37]

Together with the well in Eaton, which began producing slightly before Kokomo's, the discovery led to the Indiana Gas Boom. This discovery was directly responsible for Elwood Haynes' move to Kokomo, as a superintendent with a gas company with interests in Kokomo and Howard County. The Diamond Plate Glass Company (now part of PPG Industries) began in Kokomo in 1887, lured by the cheap and plentiful natural gas.[18] The Kokomo Opalescent Glass Works started making stained glass in Kokomo in 1888 and has been in continuous operation ever since.[38]

"City of Firsts"

As a result of the natural gas boom, Kokomo attracted an increasing number of industries, which resulted in significant technological innovations. For these industrial and technical achievements, Kokomo is officially known as the "City of Firsts."[39] Among other achievements, Kokomo was a pioneer of the United States automobile manufacturing, with Elwood Haynes test-driving his early internal combustion engine auto there on July 4, 1894. Haynes and his associates built a number of other autos over the next few years; the Haynes-Apperson Automobile Company for mass-production of commercial autos was established in Kokomo in 1898.[40] Haynes went on to invent Stainless Steel flatware in 1912 to give his wife tarnish-free dinnerware.[41] In 1938, the Delco Radio Division of General Motors (now Delphi) developed the first push button car radio.[42]

Kokomo serves as the "City of Firsts" in the food industry as well. In 1928 Walter Kemp, Kemp Brothers Canning Co. developed the first canned tomato juice because of a request by a physician in search for baby food for his clinic.[43] Kokomo is also home to the first mechanical corn picker which was developed by John Powell in the early 1920s. Kokomo was home to the first Ponderosa Steakhouse, which opened in 1965.[44] Kokomo opened the first McDonald's with a diner inside, locally called "McDiner."[45] This McDonald's theme failed nationally. Eventually, the "McDiner" closed and was converted back to a regular McDonald's restaurant.

The following inventions are associated with Kokomo:[18]

- 1894 – Elwood Haynes makes the first successful trial run of his "horseless carriage" on Pumpkinvine Pike, which is now Boulevard east of Indiana 931 (formerly U.S.31.)

- 1894 – The first pneumatic rubber tire in the US was created by D.C. Spraker at the Kokomo Rubber Tire Company.

- 1895 – The first aluminum casting was developed by William "Billy" Johnson from the Ford and Donnelly Foundry.

- 1902 – Kingston carburetor developed by George Kingston.

- 1906 – The first Stellite cobalt-base alloy was discovered by Elwood Haynes.

- 1912 – Stainless steel tableware was invented by Elwood Haynes as a response to his wife's desire for tableware that wouldn't tarnish.

- 1918 – The Howitzer shell, used in World War I, was created by the Superior Machine Tool Company.

- 1918 – The first aerial bomb with fins was produced by the Liberty Pressed Metal Company.

- 1920 – The mechanical corn picker was created by John Powell.

- 1923 – William Swern Sr. developed the first tire-building machine for mass production of auto tires [46][47]

- 1928 – The first canned tomato juice was created by Walter Kemp from Kemp Brothers Canning Company in response to a physician's need for baby food.

- 1938 – The first push-button car radio was created at Delco Radio Division of General Motors Corporation.

- 1941 – Globe American Stove Company manufactured the first all-metal life boats and rafts, known as Kokomo Kids in the US Navy.

- 1947 – The first signal-seeking car radio was created by the Delco Radio Division of General Motors.

- 1956 – Delco Radio Division of General Motors produced a transistorized signal-seeking car (hybrid) radio, which used both vacuum tubes and transistors in its radio's circuitry. This transistorized car radio was available as an option on the 1956 Chevrolet Corvette car models.[48][49]

- 1957 – Delco Radio Division of General Motors produced an all-transistor car radio, as standard equipment for the Cadillac Eldorado Brougham car model.[50][51][52]

1913 Flood

On March 21–26, 1913 Kokomo suffered severe flooding when 6.59 inches (167 mm) of rainfall occurred. The Kokomo Tribune reported at the time that the Wildcat Creek over-topped its levee to reach nearly 1 mile (1.6 km) wide after rising at a rate of 3 inches (76 mm) per hour. Damage was widespread, including loss of electrical power due to the power plant being flooded. On March 26, flooding was declared over after the water level dropped 42 inches (1,100 mm) in a 24-hour period.[53]

Ku Klux Klan

In the summer of 1923 record numbers attended rallies of the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana. On June 16, 1923, 75,000 attended a Klan rally in Terre Haute.[54] On June 21 Argos held the largest rally it had ever seen.[55] On June 26 a large Klan rally was held in Alexandria. All of this was merely a prelude to the rally planned for Kokomo. Conceived as a "monster tristate conclave" it was intended to charter 93 Indiana klans representing more than 300,000 members.[56] Some doubted the prospect of 200,000 attendees, claiming in would be "without parallel in history";[57] others predicted attendance of 300,000.[58] Extensive preparations for that number were made, including the scheduling of 1,000 interurban cars from around Indiana to Kokomo.[59] The Union Traction Company, in addition to supplying 50 cars, transported three cars of white horses to Kokomo for the parade.[60] The Kokomo Klan rented the fields surrounding its own large lot for parking, and electric amplifiers were obtained to allow the large crowd to hear the speeches.[58]

On July 4, 1923, Kokomo achieved national notoriety when it hosted the largest Ku Klux Klan gathering in history. An estimated 200,000 Klan members and supporters gathered in Malfalfa Park for a mighty Konklave and the elevation of D. C. Stephenson to Grand Dragon of the Indiana Klan.[61][62] A huge flag was used that day to collect a reported $50,000 for construction of a local "Klan hospital" so that Klan members would not have to be treated at the only local hospital, which was Catholic.[63] Both men's and women's Klans held weekly rallies and initiations in Malfalfa Park, and Kokomo's Klanswomen held meetings at the armory, the local headquarters of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan, and churches. A speech at a Baptist church was attended by 1000 Klanswomen.[64]

The Kokomo rally sent shockwaves through the national GOP, which had come to believe that the re-election of President Warren G. Harding depended on the vote of Indiana. According to the Washington correspondent of the New York World, Republicans feared that the Klan had "virtually swallowed" the Indiana Republican Party. Since the Republicans held only a 25,000 vote plurality in the state, any serious defection of African-Americans would tip the state to the Democrats.[65] In the event, Harding died within a month and Republican Calvin Coolidge succeeded him with a substantial electoral majority (including Indiana) against a divided opposition. The Klan, however, continued to dominate state politics especially after the election of Edward L. Jackson as governor.

1965 Tornado

On April 11, 1965 the southern part of Kokomo was struck by one of the 47 tornadoes that erupted over six Midwestern states, an event now known as the Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak.[66] The F4 tornado that swept through Kokomo was 800 yards (730 m) wide and killed 25 people in the surrounding area.[67] Significant damage was done to the Chrysler transmission plant. Windows were broken and the framework cracked throughout, and sections of the west wall were leveled. The Maple Crest elementary and junior high schools suffered extensive damage. The roof collapsed on the junior high school, and the framework of both schools was substantially wrecked. The Maple Crest Shell Station at the intersection of Lincoln and Washington was torn from its foundation and scattered about. Mills Drug Store at the same intersection was demolished. A house on Holly Lane was uprooted, and one on James Drive was demolished. The Maple Crest Shopping Center was extensively damaged, with Woolworth's suffering the most damage. The front and back of the one-story structure were caved in and merchandise was strewn about.[68] Numerous homes in the Maple Crest area were flattened, and the top floor of the Maple Crest apartments was blown off. The only thing left standing on the nearby Church of the Brethren was the steeple.[69] The force of the wind on the flat earth near Kokomo was so great that Ted Fujita was able to make aerial photographs of the spiral scoring on the ground.[70]

Ryan White

Kokomo served to symbolize the nation's early misunderstanding and ignorance of AIDS in the mid-to-late 1980s when Ryan White was expelled from school due to his illness. White was a teenage hemophiliac who had been infected with HIV through contaminated blood products (Factor 8). At the time blood products were often collected through state prison systems. Factor 8 was made from pooled plasma of thousands of donors. Later the plasma was screened for HIV and Hepatitis and heat treated to inactive HIV and Hepatitis. The teen had been attending Western Middle School (which is actually in Russiaville) but was ostracized by his classmates, and forced to eat lunch alone and use a separate restroom. Many parents and teachers in Kokomo rallied in support of banning White from attending the school. A lengthy administrative appeal process with the school system ensued, followed by death threats and violence against White and his family, including a bullet being fired through the window of their Kokomo home. Media coverage of the case made White into a national celebrity and spokesman for AIDS research and public education.[71] In 1987, the White family left Kokomo for Cicero, Indiana. Ryan attended Hamilton Heights High School in nearby Arcadia, and was welcomed by faculty and students.

Gas tower

The Kokomo Gas Tower had been a symbol of Kokomo since it was constructed in 1954. The tower was 378 feet (115 m) tall and had a capacity of 12,000,000 cubic feet (340,000 m3). Due to high maintenance costs of $75,000 a year, and up to $1,000,000 to paint it, the gas company decided to demolish it in 2003. Other ideas were reviewed before settling on this decision, including a plan to turn the tower into a giant Coca-Cola advertisement. On September 7, 2003, at approximately 7:30 a.m., the Gas Tower was demolished by Controlled Demolition, Inc. (CDI). Pieces of the tower were sold to the public for $20–30, and proceeds went to a planned Kokomo technology incubation center and Bona Vista.[72]

Geography and climate

According to the 2010 census, Kokomo has a total area of 18.559 square miles (48.07 km2), of which 18.5 square miles (47.91 km2) (or 99.68%) is land and 0.059 square miles (0.15 km2) (or 0.32%) is water.[1]

Kokomo has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa).

| Climate data for Kokomo, Indiana, Kokomo Municipal Airport, normals 2003–2012 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

74 (23) |

85 (29) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

107 (42) |

110 (43) |

106 (41) |

103 (39) |

91 (33) |

81 (27) |

71 (22) |

110 (43) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 32 (0) |

37 (3) |

48 (9) |

62 (17) |

72 (22) |

81 (27) |

84 (29) |

83 (28) |

77 (25) |

64 (18) |

50 (10) |

36 (2) |

60.5 (15.8) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 16 (−9) |

19 (−7) |

28 (−2) |

39 (4) |

49 (9) |

59 (15) |

62 (17) |

60 (16) |

52 (11) |

41 (5) |

32 (0) |

21 (−6) |

39.8 (4.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −26 (−32) |

−20 (−29) |

−10 (−23) |

8 (−13) |

27 (−3) |

34 (1) |

41 (5) |

37 (3) |

27 (−3) |

17 (−8) |

−5 (−21) |

−24 (−31) |

−26 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.58 (65.5) |

2.46 (62.5) |

3.03 (77) |

3.92 (99.6) |

4.43 (112.5) |

4.36 (110.7) |

4.81 (122.2) |

3.91 (99.3) |

3.45 (87.6) |

3.22 (81.8) |

3.68 (93.5) |

3.18 (80.8) |

42.4 (1,077) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71.5 | 70.5 | 63.5 | 59.25 | 62 | 63.75 | 68.5 | 71 | 65.5 | 60.5 | 63.5 | 68 | 65.625 |

| Source #1: [73] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: [74] | |||||||||||||

Environmental problems

Continental Steel Corporation

From 1914 through 1986, the Continental Steel Corporation facility produced nails, wire and wire fence from scrap steel on a 183-acre (74 ha) facility in Kokomo. Manufacturing operations in the steel plant and on other portions of the property included the use, handling, storage and disposal of hazardous materials. Steel-making operations had included reheating, casting rolling, drawing, pickling, galvanizing, tinning and tempering.

After the company filed for bankruptcy in 1986, EPA and the Indiana Department of Environmental Management investigated the plant and property and found soil, sediments, surface water and ground water contaminated with volatile organic compounds (PCBs) and several metals, including lead, arsenic, cadmium, and chromium. Lead contamination was also detected in soils on nearby residential properties.

The site was proposed to the National Priorities List as a Superfund site in 1988 and formally added in 1989.[75]

In April 2009, EPA received almost $6 million in American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to complete needed cleanup at two problems at the Continental Steel Superfund site: the former Slag Processing Area and the site's contaminated ground water. The ARRA funding helped accelerate the cleanup of hazardous waste hazardous waste on the site. In the process, total of 15 Indiana contractors or subcontractors were involved in the ARRA-funded work, creating at least 45 temporary jobs.

In August 2010, using the ARRA funds, EPA completed the cleanup of the former slag processing area of the Superfund Site. Approximately 86,000 short tons (78,000 t) of slag were moved to the site's acid lagoon area for use as fill on that portion of the site. Two feet (0.6 m) of clean soil were used to cap the former slag processing area, leaving it suitable for potential redevelopment. ARRA funds were also used to address contaminated groundwater at the site. This work included extensive groundwater sampling to determine the contaminated plume area and installation of groundwater extraction and monitoring wells. Three wind turbines will be used to generate much of the power needed to operate the groundwater extraction system.

Site cleanup was completed in August 2011.[76]

In 2016 the former site was approved as the location of a Solar farm with instillation of panels beginning in August 2016. The estimated cost of the project is $10M. [77]

Groundwater contamination

In 1995 the Indiana American Water treatment facility found groundwater beneath the city contaminated with trace amounts of vinyl chloride. In 2007, the Indiana Department of Environmental Management found groundwater at four municipal wells at containing vinyl chloride at levels exceeding the EPA maximum contaminant level in raw water.[78]

In 2011, it found one of the monitoring wells, not owned or used by Indiana American Water, had amounts of vinyl chloride that were more than 2,500 times the maximum level for drinking water.[78] IDEM has identified fourteen facilities that handle chlorinated solvents and could be sources to the contamination plume. Some of these potential sources are currently being managed under other authorities but there is no cleanup approach focusing on the ground water plume. Water from several well fields in Kokomo are blended and treated prior to distribution. A water treatment system has been successfully removing the vinyl chloride from the finished drinking water, but this is not a permanent solution to address the contaminated ground water plume.

The site was proposed to the National Priorities List and added to the Superfund in March 2015. No cleanup plan is yet in effect.[79]

Neighborhoods

These are neighborhoods in Kokomo according to the city transportation map:[80]

- Berkley Meadows

- Bon Air

- Cedar Crest

- Country Club Hills

- Cricket Hill

- Darrough Chappel

- Downtown Kokomo

- Emerald Lake

- Fairlawn

- Forest Park

- Forest Park Estates

- Fredrick Farms

- Greentree

- Highland Springs

- Holiday Hills

- Holiday Park

- Indian Heights

- Ivy Hills

- Maple Crest

- Markland Heights

- Mayfield

- Old Silk Stocking

- Orleans Southwest

- Pittsburgh Plate Glass

- Stonybrook

- Sycamore Village

- Terrace Gardens

- Terrace Meadows

- The Preserves at Bridgewater

- Urbandale

- Vinton Woods

- Water's Edge

- Western Woods

- Willowridge

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 1,040 | — | |

| 1870 | 2,177 | 109.3% | |

| 1880 | 4,042 | 85.7% | |

| 1890 | 8,261 | 104.4% | |

| 1900 | 10,609 | 28.4% | |

| 1910 | 17,010 | 60.3% | |

| 1920 | 30,067 | 76.8% | |

| 1930 | 32,843 | 9.2% | |

| 1940 | 33,795 | 2.9% | |

| 1950 | 38,672 | 14.4% | |

| 1960 | 47,197 | 22.0% | |

| 1970 | 44,042 | −6.7% | |

| 1980 | 47,808 | 8.6% | |

| 1990 | 44,962 | −6.0% | |

| 2000 | 46,113 | 2.6% | |

| 2010 | 45,468 | −1.4% | |

| Est. 2015 | 57,995 | [81] | 27.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[82] 2012 Estimate[83] | |||

Kokomo is the larger principal city of the Kokomo-Peru CSA, a Combined Statistical Area that includes the Kokomo metropolitan area (Howard and Tipton counties) and the Peru micropolitan area (Miami County),[84][85][86] which had a combined population of 119,335 at the 2012 estimate.

As of 2000 the median income for households in the city was $36,258, and the median income for a family was $45,353. Males had a median income of $38,420 versus $24,868 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,083. About 9.6% of families and 13.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.5% of those under age 18 and 9.3% of those age 65 or over.

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 45,468 people, 19,848 households, and 11,667 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,457.7 inhabitants per square mile (948.9/km2). There were 23,010 housing units at an average density of 1,243.8 per square mile (480.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 83.5% White, 10.7% African American, 0.4% Native American, 1.0% Asian, 1.1% from other races, and 3.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.3% of the population.

There were 19,848 households of which 30.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.4% were married couples living together, 16.6% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.8% had a male householder with no wife present, and 41.2% were non-families. 35.4% of all households were made up of individuals and 13.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.25 and the average family size was 2.90.

The median age in the city was 38.2 years. 24% of residents were under the age of 18; 8.8% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 25.2% were from 25 to 44; 26.2% were from 45 to 64; and 15.8% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 46.8% male and 53.2% female.

The Upper Kispoko Band of the Shawnee Nation, an unrecognized tribe, was listed as being located in Kokomo, Indiana as of 2013.[87][88][89][90][91]

Economy

Kokomo's employment is largely based in manufacturing, was hard hit by the economic downturn which led to the recession beginning in December 2007. In December 2008, Kokomo was ranked third by Forbes in its list of America's fastest dying towns, mainly as a result of the financial difficulties of the automotive industry.[92]

In May 2011, Forbes magazine listed Kokomo as one of the "Best Cities for Jobs" after the city ascended 177 places in the rankings. The same article described Kokomo's success in the past few years as "inspirational" and attributed the turnaround to "a revival in manufacturing."[93] In June 2011, Conexus released a report touting Kokomo's "rapid bounce" after the recession, and predicted a rise in income of more than 2%, assuming increased automobile production.[94]

By May 2013 Kokomo's unemployment rate was 9%, representing a 1.4% decrease in non-farm employment,[95] it was higher than the national rate of 7.6%.[96] The May 2013 statistics reported a 6.9% decline in manufacturing jobs over the previous 12 months. Government employment was 18.7% below the previous year.[95]

Major employers are

- Chrysler Group LLC

- Kokomo Transmission Plant (2,163 employees)[97]

- Kokomo Casting Plant (993 employees)[98]

- Indiana Transmission Plant I and II (2,097 employees)[99]

- Delphi Corporation

- Electronics & Safety World Headquarters

- GM Components Holdings LLC

- Haynes International

- Holder Mattress

- Syndicate Sales, Inc.

- Coca-Cola bottling plant

- Bona Vista (charity)

Government

Kokomo's current mayor is Democrat Greg Goodnight (2008–present).[100] The two previous mayors were Matt McKillip (2004–2008)[101] and Jim Trobaugh, both Republicans. The mayor is elected in a citywide vote. The city council is known as the Common Council. It consists of nine members. Six members are elected from individual districts. The other three are elected at-large.[102]

Media

Newspapers

- Kokomo Tribune, daily morning newspaper owned by Community Newspaper Holdings Inc. (CNHI).

- Kokomo Perspective, a locally owned weekly newspaper delivered every Tuesday or Wednesday.

- Kokomo Herald, weekly newspaper, a locally owned weekly founded in 1971.

- The Correspondent, The Student Voice of Indiana University Kokomo and Purdue College of Technology at Kokomo

Television

- WTTK, CBS affiliate, channel 29 (satellite of Bloomington-licensed WTTV); transmits from Indianapolis's north side

- KGOV, Kokomo government access channel, channel 2

Radio

- WFIU-FM, Jazz, Classical, NPR – 106.1 FM

- WFRN-FM, Christian Radio – 93.7 FM

- WIOU-AM, Talk, News and Sports – 1350 AM

- WIWC-FM, Christian Radio – 91.7 FM

- WMYK-FM, Rock – 98.5 FM

- WSHW-FM, Light Rock – 99.7 FM

- WTSX-FM, Hip-Hop, Gospel, Soul, Rock-n-Roll, EDM & Top 40 - 104.9 FM

- WWKI-FM, Hit Country – 100.5 FM

- WJJD-LP, Christian Radio – 101.3 FM

- WZWZ-FM, Bright Adult Contemporary – 92.5 FM

Education

Colleges and universities

- Howard College - 1863-1872[103]

- Indiana University Kokomo (IUK)

- Indiana Wesleyan University – Kokomo Campus

- Ivy Tech Community College

- Purdue College of Technology

Public school districts

- Kokomo-Center Township Consolidated School Corporation (K-12, Almost all of Kokomo) Kokomo High School (NCC)

- Taylor Community School Corporation (K-12, Indian Heights neighborhood) (MIC)

- Western School Corporation (K-12, Pine Valley/Jackson Morrow Park area) (MIC)

Private schools

- Acacia Academy (K-8)

- Agape Garden Montessori School

- Children's Christian Academy

- Christian Heritage Academy

- F.D. Reese Christian Academy (K-3)

- Redeemer Lutheran School (K-8)

- Sts. Joan of Arc and St. Patrick Catholic School (K-8)

- Temple Christian School (K-12)

- Victory Christian Academy (K-12)

Culture

Howard County Historical Society

The Howard County Historical Society occupies the Seiberling Mansion and the Elliot House, and their carriage houses. The Seiberling Mansion was built as the residence of Monroe Seiberling, one of Kokomo's richest citizens. Because of its architectural significance, the building has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1972. The Elliot House was also built as a residence; it was later adapted for use as office space. These buildings are in the Old Silk Stocking Neighborhood, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, the only neighborhood in the county to be so recognized.[104]

Parks and recreation

.jpg)

- Chief Ma-Ko-Ko-Mo Burial and Monument, east of downtown Kokomo

- Elwood Haynes Museum, located next to Highland Park[105]

- Foster Park

- Kokomo Country Club, golf club

Festivals

- Haynes-Apperson Festival, Independence Day weekend[106]

- WeberFest, Foster Park[107]

- Ivy Tech TechKnowFest, mid-November, Ivy Tech Main Campus[108]

- Kokomo Con, October, Kokomo Event Center.[109][110][111]

Sports teams

Former teams

- Indiana Mustangs, Mid Continental Football League (1991–2009), Mid States Football League (2010)

- Kokomo Dodgers, Midwest League (1955–1961)

- Kokomo CFD Saints, semi-pro baseball (1989–2002)

- Kokomo CFD Knights, semi-pro baseball (2006–2007)

Current teams

- Kokomo City of Fists Roller Girls, (Founded 2010)[112]

- Kokomo Jackrabbits, Prospect League collegiate baseball, (Founded 2015)

- Kokomo Mantis FC, Premier Development League soccer team (2016)

Sports venues

- Highland Park Stadium (CFD Investments Stadium)

- Kokomo Speedway[113]

- Memorial Gym

- Kokomo Municipal Stadium

- Wildcat Creek Soccer Complex

Entertainment

Kokomo has a 12-screen movie theater, called AMC Showplace Kokomo 12, located on 1530 East Boulevard. In addition to AMC, Kokomo also has several forms of live entertainment, including choirs, a Park Band Association, and three live theatres.

Shopping

The city's major mall is Markland Mall, which features Carson Pirie Scott, Sears and Target. The Kokomo Town Center, the former Kokomo Mall, underwent a major renovation in 2011 when it became an outdoor mall.[114]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Airports

Highways

-

US-31 to South Bend (North) and Indianapolis (South)[116]

US-31 to South Bend (North) and Indianapolis (South)[116] -

US-35 to Logansport (North) and Muncie (South)

US-35 to Logansport (North) and Muncie (South) -

IN-931 (former US 31 through Kokomo)

IN-931 (former US 31 through Kokomo) -

IN-19 to Kokomo Reservoir (North) and Tipton (South)

IN-19 to Kokomo Reservoir (North) and Tipton (South) -

IN-22 to Burlington (West) and Hartford City (East)

IN-22 to Burlington (West) and Hartford City (East) -

IN-26 to Lafayette (West) and Hartford City (East)

IN-26 to Lafayette (West) and Hartford City (East)

A major roadway traversing through Kokomo, nicknamed "stop light city",[117] US 31 had become one of the state's most congested roadways. In Howard County, there were 15 traffic signals on US 31. As part of the state of Indiana's Major Moves Project, US 31 was updated to bypass the city of Kokomo to the east. It has interchanges at SR 26, Boulevard, Markland Avenue, and Touby Pike, as well as where the current SR 931 meets the new US 31.[118] There was a similar change near South Bend and there will be one near Indianapolis. The construction in Howard County cost roughly $340 million. Construction started on the County Road 200 South bridge on November 1, 2008.[119] The new US 31 was opened November 27, 2013,[120] at which time the existing roadway was renamed SR 931.

Railroads

- Central Railroad Company of Indianapolis[121]

- Norfolk Southern Railway (out of service)

- Winamac Southern Railway (formerly part of the Columbus to Chicago Main Line)[122]

Bus service

- Trailways service to Indianapolis and South Bend

- Kokomo City-Line Trolley A fixed-route transportation system, five bus routes run past a total of exactly 275 stops, passing each stop once every hour, from 6:30 a.m. to 7 p.m., Monday through Friday. The buses also have wireless internet for riders, which like the buses, is free to riders.[123]

Trails and paths

- Wildcat Walk of Excellence – The Wildcat Walk of Excellence consists of over 3 miles (4.8 km) of paved trail that roughly follows the Wildcat Creek. The trail connects several of Kokomo's parks including Foster, Future, Waterworks, Miller-Highland and Mehlig Parks with a pedestrian bridge connecting Foster Park and the Kokomo Beach Family Aquatic Center.

- Industrial Heritage Trail – An ongoing project beginning in 2011, the Industrial Heritage Trail is currently built in two sections totaling in 4.03 miles (6.49 km) in length and follows the right-of-way of a railroad corridor. The northern segment spans 1.24 miles (2.00 km) from Apperson Way (north) to Northside Park (south). The southern section spans 2.79 miles (4.49 km) from Jefferson Street (north) in downtown Kokomo to the former Damen's Property adjacent to SR931 on the city's south side. Once completed, the Industrial Heritage Trail will span 5.6 miles (9.0 km) between SR931 on the city's north and south side.

- Nickel Plate Trail – Currently connecting Rochester to Peru, the trail ends in Cassville with plans to connect to Kokomo in the near future.

Health care

- St. Vincent Kokomo Hospital, opened in 1913,[124][125][126]

- Community Howard Regional Health, incorporated in 1958[127]

Notable people

- Brandon Beachy, MLB pitcher Los Angeles Dodgers, Northwestern High School (Indiana) graduate

- Alicia Berneche, operatic soprano

- Rupert Boneham, contestant on TV series Survivor, Libertarian candidate for Indiana Governor in 2012

- Norman Bridwell, author of the Clifford the Big Red Dog children's books

- Quautico (Tico) Brown, former Continental Basketball Association player

- Steve Butler, six-time Sprint Car National Champion

- Calibretto 13, band

- Kaitlyn Christopher, Miss Indiana USA 2005

- Dave Darland, auto racer

- Rowdy Elliott, baseball player

- Elwood Haynes, inventor, automotive pioneer

- Bud Hillis, U.S. Representative

- Margaret Hillis, pianist, founder of Chicago Symphony Chorus

- Nellie Keeler, child circus performer

- Don Johnson, professional bowler/PBA Hall-of-Fame member

- Steve Kroft, 60 Minutes correspondent

- Jim "Goose" Ligon, former ABA basketball player

- Strother Martin, actor

- Clay Myers, photographer, animal welfare advocate

- Kent C. Nelson, past CEO of United Parcel Service

- John O'Banion, singer

- Jack Purvis, jazz musician

- Jimmy Rayl, "Splendid Splinter," Indiana Pacers 1967–1969, two-time All-American Indiana University

- Robert S. Richardson, astronomer

- Tod Sloan, jockey

- Tavis Smiley, PBS presenter

- "Sylvia" (Sylvia Jane Kirby), singer

- Floyd Talbert, soldier in World War II (his actions were featured in the TV miniseries Band of Brothers)

- Joe Thatcher, pitcher for MLB Chicago Cubs

- Pat Underwood, former MLB pitcher, Detroit Tigers

- Tom Underwood, former MLB pitcher, Philadelphia Phillies, St. Louis Cardinals, Toronto Blue Jays, New York Yankees, Oakland A's and Baltimore Orioles

- William N. Vaile, Congressman[128]

- Ryan White, AIDS activist

In popular culture

- The Man from Home (1908), a play by Booth Tarkington and Harry Leon Wilson, involves a lawyer from Kokomo who travels to Europe but returns to the city in the happy ending.[129]

- The Kid from Kokomo (1939; also sometimes called Broadway Cavalier) is a comedy film about an orphan from Kokomo who refuses to box until his mother is found. The film was based on a story by Dalton Trumbo.[130]

- In the 1947 film Mother Wore Tights, Betty Grable and Dan Dailey sing a song entitled "Kokomo, Indiana".[131]

- Kokomo is the setting of Allan Dwan's nostalgic 1953 musical Sweethearts on Parade.[132]

- In the 1980 film "Blues Brothers," the roadhouse "Bob's Country Bunker" is identified by Elwood Blues as being located in Kokomo.[133]

Sister city

See also

References

- 1 2 "G001 - Geographic Identifiers - 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ↑ "US Census". US Census. Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Kokomo (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau".

- ↑ "YEAR IN REVIEW: Annexation, Kokomo recovery top 2011 headlines". Kokomo Tribune. December 31, 2011.

- ↑ "A Look Back as We Move Forward". The Kokomo Tribune. March 28, 1999. p. 58. Retrieved August 16, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 Baker, Ronald L. (1984) Hoosier Folk Legends. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253203341. p. 184.

- 1 2 Leiter, Carl (February 28, 1965). "Kokomo Legend". Kokomo Morning Times. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- 1 2 Morrow, p. 48.

- ↑ Dunn, Jacob Piatt (September 1912). "Indiana Geographical Nomenclature". Indiana Quarterly Magazine of History. Indiana University. 8 (3): 110–111.

- 1 2 Morrow, p. 202.

- ↑ Pollard, p. 320

- ↑ Morrow, pp. 56–58.

- ↑ Morrow, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Time Line of Howard County, 1844–". Kokomo-Howard County Public Library. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ↑ Pollard, pp. 326–27

- ↑ Pollard, p. 330.

- 1 2 Pollard, p. 326.

- ↑ Morrow, pp. 202–03.

- ↑ An Act to grant the Right of Preemption to actual Settlers on the Lands acquired by Treaty from the Miami Indians in Indiana, 9 Stat. 50 (August 3, 1846).

- ↑ Morrow, p. 68.

- ↑ Pollard, Otis C. "Newspapers". History of Howard County. by Jackson Morrow (Indianapolis: B.F. Bowen & Co. [1909?]), Vol. I, pp. 304–18 ("Newspapers"), pp. 304–05.

- ↑ Morrow, pp. 112–13.

- ↑ Pollard, pp. 327–28.

- ↑ Pollard, Otis C. "Railroads". History of Howard County. by Jackson Morrow (Indianapolis: B.F. Bowen & Co. [1909?]), Vol. I, pp. 416–21 ("Railroads"), pp. 416–19.

- ↑ Watt, William J. (1999) The Pennsylvania Railroad in Indiana. Indiana University Press. p. 30.

- ↑ Railroads, pp. 419–20.

- 1 2 3 4 Leiter, Carl. "The Case of Dr. Henry Cole". From Out of the Past. Kokomo-Howard County Public Library. undated clipping.

- ↑ Pollard, Otis C. "Crimes and Casualties". History of Howard County. by Jackson Morrow (Indianapolis: B.F. Bowen & Co. [1909?]), Vol. I, pp. 282–304 ("Pollard"), p. 292-93.

- ↑ "General News". The New York Times. October 29, 1866. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- 1 2 Pollard, p. 293.

- 1 2 3 Booher, Ned and Linda Ferries, Kokomo: A Pictorial History (St. Louis: G. Bradley: 1989), p. 28.

- ↑ Pollard, pp. 294–95.

- ↑ Morrow, pp. 232–34.

- ↑ "History of Kokomo Opalescent Glass". Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ↑ "City of Kokomo, Indiana". Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ Gordon Library: Archives & Special Collections – WPI

- ↑ "Stainless Steel". Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ ONDAS Media Selects Delphi as First Strategic Investor and Technology Provider to Help Bring Satellite Radio to Europe

- ↑ "Walter Kemp Develops Canned Tomato Juice". American Profile. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ Stephens, Caleb (April 21, 2003). "Local Ponderosa restaurants fall from six to two". Bizjournals.

- ↑ "'McDonald's With Diner Inside' Debuts". 2001. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ Howard County Historical Society

- ↑ http://howardcountymuseum.org/news/a+new+name+on+the+list+of+firsts/61

- ↑ Christian Science Monitor Newspaper, Article "Chevrolet Restyles Sleek 1956 Corvette", February 20, 1956, p.22

- ↑ 1956 GM Year-End Annual Report, p. 15

- ↑ 1956 GM Year-End Annual Report, 1957 Cadillac Eldorado Brougham car model introduction announcement, p. 15

- ↑ Radio & TV News, August 1957, "Delco's All-Transistor Auto Radio", p. 60

- ↑ The Cadillac Serviceman, Volume XXXI, No.4, April 1957 issue, Pg 34

- ↑ "The Great Flood of 1913" The Kokomo Tribune, March 25, 2013

- ↑ "Klansmen at Terre Haute". Indianapolis News. June 18, 1923. p. 8. Retrieved October 11, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ "K.K.K. Meeting". Argos [Indiana] Reflector. June 28, 1923. p. 1. Retrieved October 11, 2016 – via newspqaper.com.

- ↑ "Klan Plans Big Time at Kokomo". Logansport [Indiana] Pharos-Tribune. July 2, 1923. p. 7. Retrieved October 11, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Ku Klux Klan Meeting in Crothersville". [Seymour, Indiana] Tribune. July 2, 1923. p. 1. Retrieved October 11, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "5 Special Cars to Klan Meeting". [Columbus, Indiana] Republic. July 3, 1923. Retrieved October 12, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ "[no title]". Waterloo [Indiana] Press. June 28, 1923. p. 4. Retrieved October 11, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Special Cars of Klan to Kokomo". [Seymour, Indiana] Tribune. July 3, 1923. p. 1. Retrieved October 11, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ McVeigh, Rory, The Rise of the Ku Klux Klan: Right-wing Movements and National Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: c2009), pp. 1–4.

- ↑ Wyn Craig Wade (1998). The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. Oxford University Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-19-512357-9.

- ↑ "Konklave in Kokomo" by Robert Coughlan, The Aspirin Age: 1919–1941, pp. 105–129. ed. Isabel Leighton, Simon and Schuster, 1949

- ↑ Kathleen M. Blee (2009). Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s. University of California Press. p. 138. ISBN 0-520-94292-2.

- ↑ "Republicans Fear Ku Klux Klan in Indiana". The Hancock Democrat [Greenfield, Indiana]. July 12, 1923. p. 6. Retrieved October 12, 2016 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ "April 11, 1965, Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak". National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office, Indianapolis, IN. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ↑ "NOAA Remembers the Midwest's Deadly 1965 Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak". NOAA Magazine. April 11, 2005. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Kokomo's southside flattened by storm," Kokomo Morning Times, April 13, 1965, p2.

- ↑ "Maple Crest residents sift debris for lost belongings," Kokomo Morning Times, April 13, 1965, p2.

- ↑ Grazulis, Thomas P. (2001) The Tornado: Nature's Ultimate Windstorm. Norman, Oklahoma, University of Oklahoma Press, p. 44, fig. 3.8.

- ↑ AIDS Boy Banned From Attending School – 1st August 1985

- ↑ "Crowds flooded the intersection of Firmin and Home Avenue". Kokomo Tribune. December 16, 2005.

- ↑ Monthly Averages for Kokomo, IN (46901). weather.com

- ↑ Average Weather For Kokomo, Indiana, USA. weatherspark.com

- ↑ "Indiana Superfund sites". Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ↑ "Region 5 Cleanup Sites, Continental Steel Corp.". Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ↑ "$10M solar farm approved for ex-steel plant site in Kokomo". www.ibj.com. Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- 1 2 Carson Gerber (June 21, 2015). "EPA launches investigation into polluted groundwater beneath city". Kokomo Tribune (IN). Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Kokomo Contaminated Ground Water Plume". Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ↑ City transportation map. cityofkokomo.org

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ↑ METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS AND COMPONENTS Archived May 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Office of Management and Budget, May 11, 2007. Accessed 2008-08-01.

- ↑ MICROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS AND COMPONENTS, Office of Management and Budget, May 11, 2007. Accessed 2008-08-01.

- ↑ COMBINED STATISTICAL AREAS AND COMPONENT CORE BASED STATISTICAL AREAS, Office of Management and Budget, May 11, 2007. Accessed 2008-08-01.

- ↑ "First director hired for Purdue's new Native American Educational and Cultural Center". Purdue University. August 23, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ↑ Susan O'Leary (January 6, 2008). "Tribal groups call Indiana home: Commission spreading word on American Indian presence, needs". nwi.com. Munster, Indiana. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Native American Tribes of Indiana". Archived from the original on August 10, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Tribal Directory of Northeastern Indian Tribes". Indians.org. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Shawnee". Four Directions Institute. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ↑ Kotkin, Joel; Shires, Michael (December 9, 2008). "America's Fastest-Dying Towns". Forbes. Retrieved December 11, 2008.

- ↑ Kotkin, Joel; Shires, Michael (May 2, 2011). "The Best Cities For Jobs". Forbes. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ "2011 Manufacturing + Logistics Indiana State Report" (PDF). Ball State University. June 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- 1 2 "Economy at a Glance: Kokomo, IN". Bureau of Labor Statistics. July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Economy at a Glance: United States". Bureau of Labor Statistics. July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Kokomo Transmission Plant". Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Kokomo Casting Plant". Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- ↑ "Indiana Transmission Plant I". Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- ↑ "Kokomo Mayor". City of Kokomo, Indiana. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ↑ City of Kokomo Indiana | Mayors Office Archived December 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Kokomo Common Council Members". www.cityofkokomo.org. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ↑ http://www.kokomoschools.com/domain/714

- ↑ "Howard County Historical Society". Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Elwood Haynes Museum". City of Kokomo. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Haynes-Apperson Festival". Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ↑ "WeberFest 2012 – August 3 and 4". Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ↑ "Events". Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Kokomo Con". Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Con to showcase comics, pop culture, gaming". Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Kokomo-Con 2014 - Comic Convention on UpcomingCons.com". www.upcomingcons.com. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Kokomo City of Fists Roller Derby". Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ↑ Kokomo Speedway

- ↑ "Kokomo Mall transforms into Kokomo Town Center". Kokomo Tribune. May 30, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Kokomo Municipal Airport". City of Kokomo. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ↑ "New U.S. 31 bypass opens around Kokomo".

- ↑ "Kokomo to become Not-so-Stoplight City". Kokomo Perspective. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Welcome to the US 31 Kokomo Corridor Project Website". Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ↑ "U.S. 31 bypass work begins". Kokomo Tribune. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ↑ "On Cruise Control". Kokomo Tribune. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ↑ "CENTRAL RAILROAD OF INDIANAPOLIS (CERA)". Genesee & Wyoming. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ↑ "State of Indiana 2011 Rail System Map" (PDF). Indiana Department of Transportation. 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ Public Transportation for City of Kokomo. cityofkokomo.org

- ↑ "St. Joseph of Kokomo, Ind., marks centennial". Catholic Health Association. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ↑ "St. Joseph Hospital – Our History". St. Vincent Health. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ↑ Fialka, John (2003). Sisters: Catholic nuns and the making of America. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-26229-7. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ↑ "Community Howard Regional Health History". Community Howard Regional Health. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ↑ The New York Times, "Congressman Vaile Dies In Automobile," July 3, 1927

- ↑ Bordman, Gerald & Hischak, Thomas S. (2004) The Oxford Companion to American Theatre. 3rd ed.: Oxford Press, p. 411.

- ↑ "The Kid from Kokomo". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ↑ Whorf, Michael (2012). American popular song composers : oral histories, 1920s-1950s. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 148. ISBN 9780786465378.

- ↑ Lombardi, Frederic, Allan Dwan and the Rise and Decline of the Hollywood Studios (McFarland: 2013), p. 267; News clipping, The Kokomo Tribune, (August 8, 1953), p. 8. Accessed April 28, 2013.

- ↑ http://bluesbrothersofficialsite.com/gi-174026-we-have-both-kinds-country-and-western.html

- ↑ "Kokomo is China-bound". Kokomo Perspective. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

Bibliography

- Pollard, Otis C. (1909). Early Days of Kokomo. History of Howard County. I. Indianapolis: B.F. Bowen & Co.

- Morrow, Jackson (1909). History of Howard County. I. Indianapolis: B.F. Bowen & Co.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kokomo, Indiana. |

-

Kokomo travel guide from Wikivoyage

Kokomo travel guide from Wikivoyage - City of Kokomo