Brown Building (Manhattan)

|

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory | |

|

(2011) | |

| |

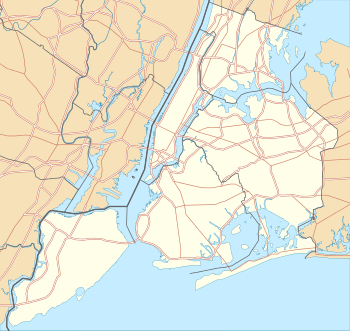

| Location | 23-29 Washington Pl, Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°43′48″N 73°59′45″W / 40.73000°N 73.99583°WCoordinates: 40°43′48″N 73°59′45″W / 40.73000°N 73.99583°W |

| Built | 1900-01[1] |

| Architect | John Woolley |

| Architectural style | Neo-Renaissance |

| NRHP Reference # | 91002050 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 17, 1991[2] |

| Designated NYCL | March 25, 2003 |

The Brown Building is a ten-story building that is part of the campus of New York University (NYU). It is located at 23-29 Washington Place, between Greene Street and Washington Square East in Greenwich Village, New York City.

It was built in 1900–01, by an architect named John Woolley, who made the building from iron-and-steel, which was designed in the neo-Renaissance style.[1] It was originally named the Asch Building after its owner, Joseph J. Asch.[3] During that time, the Asch building was known for its “fire proof”[4] rooms, in which attracted many garment makers,[4] including the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, which was the site of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire that killed 146 garment workers on March 25, 1911.

Majority of the workers who occupied the Ash Building, were female immigrants. The immigrants were underpaid and came to the United States for a better life, although they were working in terrible conditions within the factory. The building top three floors[5] were occupied by Russian immigrants, that goes by the name Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, who were the owners of the Triangle shirtwaist factory.

Even though, the immigrants were provided a job, their work environment was not safe. The rooms were overcrowded with few working bathrooms and no ventilation, sweltering heat or freezing cold.[6] In regards to work conditions, the Asch building at the time were not complying with several requirements that were needed, to ensure the safety of the building. The rooms in the upper three floors were packed with flammable objects, including clothing products hanging from lines above workers' heads, rows of tightly spaced sewing machines, cutting tables bearing bolts of cloth, and linen and cotton cuttings littering the floors,[5] that resulted in a massive spread of fire, that occurred in the matter of seconds. The water hoes were not installed properly to the water tower, due to the lack of understanding on behalf of the owners. The owners installed a fire escape that was not durable enough to hold many people and there were no sprinklers installed in the building. The rooms on each floor were overcrowded because there was no limit as to how many people could occupy one floor. The stair cases did not have any “landing” which were a hazard that could trip people down the stairs, due to the lack of lights, in which made the stair way dark and hard to see.

A survivor of this incident indicated there had been a blue glow coming from a bin under a table where 120 layers of fabric had just been stacked prior to cutting. Fire rose from the bin, ignited the tissue paper templates hung from the ceiling and spread across the room. Once ignited, the tissue paper floated off haphazardly from table to table, setting off fires as it went.[6] In the after math of the tragic event, many workers had died. Workers had died from inhaling thick smoke and from burning in the fire. The fire started to spread,and people began to jump out of the building because the stairway was blocked and the elevators were not functioning properly. Workers piled up at the entrance of the stairway because the stairway was too dark to see their way down the steps, that had no landing and were crushed by the door because of the mass panic and fear from the people running to the dark stairway. The other entrance of the stairway were locked by management because they wanted to prevent workers from stealing company garments. As for the elevators, the owners and their family went into the elevator, which only could have held twelve people and escaped the building. In request of the owner, they told the elevator operator to send the elevator back up; however, by the time the elevator made its way back, the fire was fully engaged on the eighth floor and quickly spreading to the ninth.[6] This had forced the workers to jump out the windows and jump into the elevator shaft that was nine-stories down. Although there was the option of using the fire escape to get out of the burning building, only few did manage to escape through it. With many workers going through the fire escape, the fire escape eventually collapsed. Prior to the fire escape collapsing, people still could not make it to the ground safely, because the ladder from the fire escape did not reach the ground, nor was it close enough for people to jump down, in which led to many more deaths.

The Fire Department of New York did not play a big role, during the fire of the Triangle shirtwaist factory. Since buildings were evolving, during the time of the industrialization period, the fire department were not up to date. They did not have the proper equipment to take down the fire, such as the ladder, in which “could only reach to the sixth floor, fully two floors below the level of fire.[6] the owners Max Blanck and Isaac Harris were charged with “criminal negligence”,[5] and faced multiple lawsuits from the victims’ families. As a result of this event, people hoped for change, regarding the matter of labor. They hoped that this event will bring change to building regulations, “such as mandatory fire drills, periodic fire inspections, working fire hoses, sprinklers, exit signs and fire alarms, doors that swung in the direction of travel and stairway size restrictions.”[6]

The fire led to wide-ranging legislation requiring improved factory safety standards and helped spur the growth of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union. The building survived the fire and was refurbished. Three plaques on the southeast corner of the building commemorate the men and women who lost their lives in the fire.

NYU began to use the eighth floor of the building for a library and classrooms in 1916.[1] Real estate speculator and philanthropist Frederick Brown later bought the building and subsequently donated it to the university in 1929, when it was renamed as the Brown Building.[7][8][9][10] In 2002, the building was incorporated into the Silver Center for Arts and Science.[8]

The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and was named a National Historical Landmark in 1991.[11][12] It was designated a New York City landmark in 2003.[13]

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S. (text); Postal, Matthew A. (text) (2009), Postal, Matthew A., ed., Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1, pp.64-65

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Historical plaque on the southeast corner of the Brown Building, facing Greene Street, placed by the New York Landmarks Preservation Foundation in 2003.

- 1 2 "Building Where 146 Died Still Stands". National Newspapers Core. Mar 12, 2011. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - 1 2 3 Riggs, Thomas (2015). Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale. pp. 1341–1343.

Triangle Shirtwaist Fire

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jones, Stephen D. (August 2011). "The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire: Difficult Lessons Learned on Fire Codes and Safety" (PDF). http://media.iccsafe.org/news/iccenews/2015v12n10/tsfjonesbsj.pdf. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Brown 8th Floor Directory". New York, NY: NYU. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- 1 2 "NYU Campus Map". New York, NY: NYU. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ↑ "175 Facts about NYU - Brown Building". New York, NY: NYU. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ↑ "FAS Building Table". New York, NY: NYU. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Registration" (pdf). National Park Service. 1989-09-26.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Registration" (pdf). National Park Service. 1989-09-26.

- ↑ Harris, Gale. "Brown Building (formerly Asch Building) Designation Report" New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (March 25, 2003)

External links

Media related to Triangle Shirtwaist Factory building at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Triangle Shirtwaist Factory building at Wikimedia Commons- Triangle Fire Open Archive: Landmark Designation, Brown/Asch Building